I bought my St. Dymphna medallion in New Orleans on a muggy August afternoon in 2016, the kind of day when high summer begins to tip over into the peak of hurricane season. Beads of moisture dotted my hairline, not sweat but water pulled from the oversaturated air. The cathedral gift shop had bins and bins of medallions, a saint for every need — Jude for lost causes, Anthony for lost objects, Joan of Arc for lost wars. I ran my hands through them, making the metal shift and clink in a satisfying way, before picking one out, paying for it and sliding it onto a thin silver chain.

As I fixed the clasp at the back of my neck, I offered up a silent prayer to the patron saint of mental illness: “Please, Dymphna, fix my brain.”

You may unsubscribe from any of our newsletters at any time.

Outside, the atmosphere crackled with coming storms and peculiar magic.

That magic came back to me again three years later, on a train rattling across the Belgian countryside. Travelling can sometimes feel like falling in love — there’s the same sense of giddiness, the same wild curiosity — and everything around me made me feel like I was waking up from a long stupor. The view from my window looked like a landscape painted by a Flemish master, and the spring air was strangely sweet in a way I’d never smelled before. I kept pausing to take in big lungfuls, trying to print the scent on my memory.

But the magic was more than just the thrill of being somewhere new; it was knowing that with every mile of track that passed, I was getting closer to Geel. This city, 50 kilometres southeast of Antwerp and small enough that it didn’t even warrant a dot on the map in my guidebook, was the site of Dymphna’s martyrdom. It is also home to a remarkable social psychiatry program that sprung up in the wake of her death.

I dreamed of a place like Geel long before I knew it was real. Through all the time I’d spent in Canada’s psychiatric system — years of white-knuckling it through months-long wait-lists just to get an intake appointment, late nights in the ER with panic attacks that wouldn’t stop, wards with doors that lock behind you with a gut-wrenching click — I’d tried to imagine how it might be different. I fantasized about a system where care is ongoing and mental health isn’t treated as a binary of “fine” and “crisis;” where patients are considered complex individuals rather than a list of dysfunctions; where clinicians understand the difference between staying alive and actually living.

The stigma against mental illness permeates well past the medical system into all aspects of society, from the hushed tones we use when we talk about it, to the looks we exchange when a dishevelled man is being too chatty on the subway, to the way we casually pepper our conversations with words like crazy, insane, psychotic. Managing the distress caused by mental illness is hard enough, and that difficulty increases exponentially when you have to exist in a world that fears and hates your illness. To fix all that, you would have to change society entirely, but that’s exactly what Geel has done. And it all started with St. Dymphna.

According to her legend, Dymphna was born in the small Irish kingdom of Oriel sometime in the seventh century. Her father, Damon, was the king; he was also a pagan. Her mother was a Christian, and like so many mothers in these types of stories, she’s rarely accorded the dignity of a name. All we get are a few nebulous adjectives: beautiful, loving, virtuous.

The interfaith nature of Dymphna’s parents’ marriage was reflective of the changing religious landscape in Ireland at the time. It had been 200 years since a Romano-British bishop named Patricius allegedly drove out all the snakes, helping to popularize Christianity. By the time Dymphna came along, the faith was spreading rapidly across the island. It was still very new though, and, like Damon, many continued to worship the old gods of the Celts.

Dymphna, however, was raised Christian, and at the age of 14, she took a vow of chastity and dedicated her life to Christ. The timing of these particular solemn promises might have been influenced by a decline in her mother’s health — a bargain for her recovery — since shortly afterwards, Dymphna’s mother died.

More on Broadview: Anne Thériault on her spiritual journey to Geel, Belgium

Damon and his daughter were distraught. As months went by and his grief deepened, his counsellors began to worry. They urged him to move on and remarry. Eventually, he agreed, but only on the condition that his new wife would be as beautiful and accomplished as his last. His men travelled all over the country to find a woman good enough for Damon, but they failed. His mental state continued to deteriorate, and he developed a frightening new fixation: marrying Dymphna.

These days, Damon’s breakdown might be called brief reactive psychosis, an extreme break from reality triggered by a stressful life event; in the 600s, it was termed “madness.” But a mad king is still a king, and Damon wielded a huge amount of power. His pursuit of his daughter intensified, her refusals unacceptable in his eyes. As a last entreaty, she begged him to give her 40 days to decide, which she used to secretly prepare to leave. Once everything was in place, she fled with her priest, Father Gerebernus, first on a ship to the port city of Antwerp, then on to Geel.

It must have been a terrifying journey. Travelling over water was dangerous in those days, and a trip through the Irish Sea and across the English Channel would have been perilous. Dymphna also probably experienced the same mix of feelings many women do when they make it out of an abusive situation: relief, of course, but also a profound sadness. Damon, after all, was her only living parent. All of this must have been compounded by guilt, since disobeying her father went directly against one of the core values of Christianity: honour thy father and thy mother.

Maybe it was those complicated feelings that led Dymphna to what she did next: use her considerable resources to build a hospice for the poor and sick. According to some versions of her legend, this hospice particularly served those with mental or neurological illnesses. If this is true, Dymphna would have been centuries ahead of the rest of Europe. Most medieval hospices turned away people with mental illness, believing them to be contagious or possessed or both. But Dymphna seemed determined to help others who suffered the way her father did.

It wasn’t long before Damon’s scouts heard stories about a young woman spending Irish gold in the Flemish countryside. Damon immediately went to Geel, where the owner of a local inn pointed him in his daughter’s direction. After finding her, Damon had her priest executed in front of her. But even that didn’t convince Dymphna to marry him, so Damon beheaded her with his own sword.

It’s hard to imagine a lonelier or more frightening death — in a foreign land, at the hands of her father, at just 15 years old. Damon’s soldiers, who probably teased and played with Dymphna when she was a little girl, looked on and did nothing. Maybe that was the worst part. Or maybe it was all so awful that there was no one single part that could be called the worst.

Some traditions hold that mentally ill patients from her hospice also witnessed Dymphna’s death, and they were immediately, miraculously cured. As this story spread, Geel became a place of pilgrimage for the “mad” — anyone with mental illness, epilepsy, neurological disorders and cognitive differences. Pilgrims flocked to Dymphna’s burial site, and more cures were recorded. At some point, she began to be venerated as a local saint.

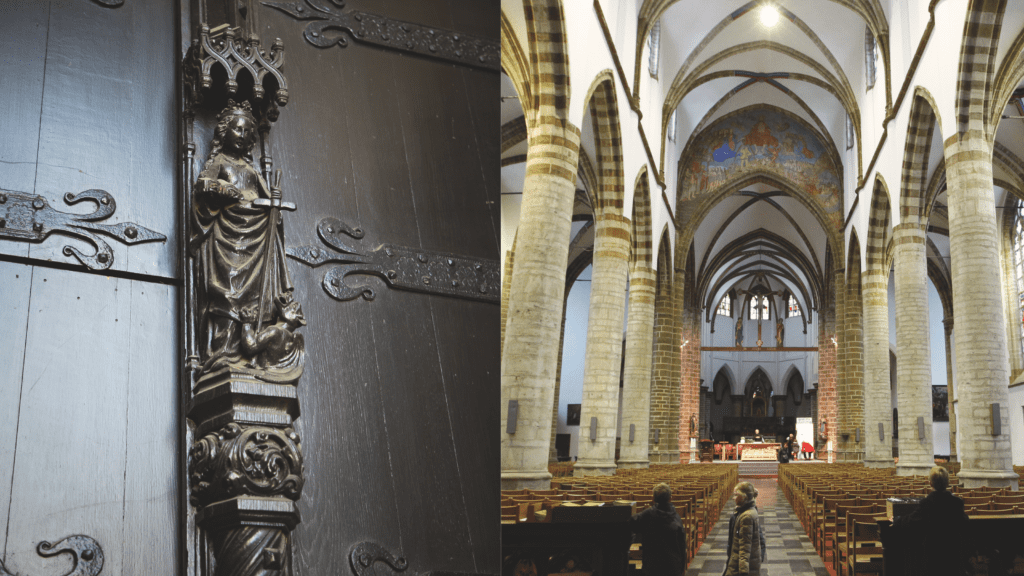

More than a dozen centuries after Dymphna’s death, Geel is filled with statues and paintings made in her likeness. The camera roll on my phone is filled with various depictions of her, each of them unique but with common elements: a crown to show her royal status; green robes to show her Irish heritage; a Bible to show religious devotion; a sword to show how she died; and a demon representing madness crushed beneath one foot. Many of her statues are adorned with candles and pots of fresh flowers. Always her face holds the same impassive look, one that seems to say: you don’t understand, but I forgive you anyway.

The first church dedicated to St. Dymphna was built in 1349, about 100 years after her legend was recorded by Petrus van Kamerijk, a canon of Cambrai. The influx of pilgrims hoping to be healed of mental health issues increased dramatically, and in the mid-15th century, the church decided to add a dormitory to house them. There, women from the town cared for the pilgrims as they underwent a nine-day healing ritual. A key part of this “treatment” involved crawling on the ground beneath Dymphna’s remains, which had been disinterred and placed in an elaborate shrine.

As time went by, these remains slowly diminished. Her skull was lost at some point — bricked up in a church pillar, according to some stories — and then there was the all-too-generous 17th-century prior who apparently gave away pieces of her without consulting his colleagues. The more the myth of Dymphna grew, the more the real Dymphna shrank.

Those who travelled to Geel and weren’t immediately cured might stay for years, or even the rest of their lives. Sometimes this was their choice, but some were abandoned by family members. When the dormitory became inadequate to house everyone, the people of Geel took pilgrims into their homes. This was partly religiously motivated (charity is a virtue, after all), but it was also practical. In exchange for room and board, families expected help around the house or in the fields.

As time went on, pilgrims became known as “guests” or “boarders” and a regular part of village life and culture. The result was that many of the behaviours associated with serious mental illness were normalized in Geel, which meant that the boarders were able to navigate the world without worrying about being harmed or stigmatized, alleviating a lot of their suffering.

While all of this was happening in Geel, attitudes toward mental illness were also radically shifting across the rest of Europe, although in a much different direction. Madness had long been viewed as a domestic problem to be solved by families or parish priests, but by the late medieval period it started to be seen as more of a public health issue. Hospitals like London’s Priory of St. Mary of Bethlehem (colloquially known as Bedlam) were transformed into “madhouses” that specialized in caring for the mad — if filthy conditions and brutal restraints can be called “care.”

In the 18th century, the Enlightenment touched off a wave of reforms in mental health treatment. Instead of viewing madness as an affliction best handled by locking its sufferers away, a new school of doctors asserted that things like rest, fresh air and a generally humane approach could vastly improve the prognoses of the mentally ill. The madhouse model fell out of favour, and progressive doctors began to promote the idea of “asylums,” huge, sun-filled buildings where patients could escape the pressures of society and access various therapies.

These radical reformers began to take an interest in Geel, although their opinions of its so-called “Colony of the Mad” were divided. Some thought that the boarder practice was backward, an archaic church system that left the mentally ill to languish without any kind of medical care. “Treatment and freedom cannot go hand in hand. In Geel there is no treatment, and the alienated have nothing but freedom which is harmful to them,” argued Dr. Ferrus, a French physician, quoted by Jules Duval in his 1867 text Gheel ou une colonie d’aliénés (Geel or a colony of the alienated).

Many were deeply skeptical that illiterate farmers could know better than medical professionals. But others saw Geel as an outstanding success. French doctor Philippe Pinel, sometimes referred to as the father of modern psychiatry, remarked that “the farmers of Geel are arguably the most competent doctors; they are an example of what may turn out to be the only reasonable treatment of insanity and what doctors from the outset should regard as ideal.” His student and successor, Jean-Étienne-Dominique Esquirol, visited Geel in 1821 and marvelled over how calm and content the boarders seemed, especially in contrast to their institutionalized counterparts. The debate became known as “The Geel Question”: was the boarder system more humane than that of the asylum, and was it something that could be replicated elsewhere?

Some of the criticisms of the Geel system were valid. The church’s oversight was lax, and families who were abusive didn’t face consequences. Residents who might be struggling with challenging behaviours from boarders lacked resources; some even resorted to using physical restraints.

The family-care program isn’t miraculous; it is as profoundly human as Dymphna’s life story. It’s proof of how well we can love each other when we practise radical acceptance.

When the Belgian state psychiatric system took over the management of the family-care program in 1850, it did its best to address all of these issues while keeping the elements that made it unique and successful. The government outlawed the use of restraints on boarders and introduced strong consequences for families who abused their charges. They also built a hospital at the edge of town along with large bathhouses for the boarders’ use.

The hospital was a low, elegant red-brick building that looked more like a country retreat than a medical centre. Boarders were assessed there before being placed with a family, and staff monitored individual cases. The beds were for those experiencing a crisis and in need of a higher level of care than the families could provide. But this was viewed as a short-term coping mechanism rather than a long-term solution.

The bathhouses were deliberately separate from the hospital so they felt safe and non-threatening, especially to anyone who had experienced institutionalization before coming to Geel. Boarders visited each week not only for hygiene and health reasons, but also so that doctors could check in about their home life without the family overhearing. This, along with regular home checks, helped ensure boarders were safe and thriving in their placements.

Sure, families who took in boarders received a small stipend, but the real incentive to participate in the program was a sense of pride in the work they did. As the Brussels correspondent for London’s Pall Mall Gazette wrote in the 1870s, “It is the personal interest of the inhabitants to do their duty well by the patients, as they are [e]ntrusted only to people whose moral fitness and means of existence are approved. In fact, a family at [Geel] is not considered respectable if lunatics are not [e]ntrusted to it, and the withdrawal of them from care constitutes a heavy punishment.”

The family-care system continued to gain international attention (Vincent van Gogh’s father even considered sending his son there). The program saw incredible growth in the early 20th century. At its peak in 1938, nearly 4,000 boarders lived in a town of 16,000, and services had expanded to include a school for children with mental illnesses and cognitive differences. But then the Second World War began, and Germany soon occupied Belgium. Although family care continued throughout the war, numbers declined.

Today, 232 boarders live in Geel with 187 families. The size of the program isn’t all that’s changed in the last 80 years. The shift from agricultural to urban living means many families don’t have someone who can be home with a boarder during the day, and the rise of psychiatric drugs means far fewer people require supported living. Many of the boarders in the 1930s had diagnoses like depression, anxiety or obsessive-compulsive disorder that can be more easily managed now with medication. These days, boarders are more likely to live with either serious cognitive disabilities or mental illnesses, like schizophrenia, that are more challenging to treat.

Incredibly, those diagnoses are not disclosed to the foster families. Instead, they approach their boarders as individuals with their own behaviours and personality quirks rather than a list of symptoms. Instead of pathologizing the boarders, the aim is to highlight their abilities and strengths. “[The] focus [is] no longer on cure, but on care,” says hospital spokesperson Johan Claeys. “The focus is on a normal daily life in an average family, out of institutions.”

Most radically, the program works to reshape society to be fully inclusive instead of forcing people with mental illnesses to try to accommodate an intolerant society. The end goal is for boarders to be able to live in a world that accepts them for who they are. Even the term “boarder” is meaningful. It describes a social role within the community, unlike “patient,” which can indicate a dysfunctional state that requires fixing.

Boarders often live with the same foster family through multiple generations; when the parents become too old to care for them, they will move in with the adult children. These second-generation caregivers have an extra-close bond with the boarders, since they’ve often known them for their entire lives. They also learned from a very young age not to view mental illness as strange or frightening. Kathleen Goovaerts, who owns the Roosendaelhof Hotel in Geel, has a lot of fond memories of growing up next door to a family with three boarders. “They were so different from the other adults,” says Goovaerts. “They were always ready to play with us, to be on our level. I didn’t realize then how special it was, because it was just ordinary for us.”

Many elements of the boarder program have remained unchanged over the centuries; and yet, some still feel like a modern departure from the West’s approach to mental illness. It’s certainly a far cry from my own experiences. At best, I’ve found mental health care in Canada difficult to navigate. At worst, it’s a system that has tried to “fix” me through coercion and threats. And I know that I’m one of the lucky ones. Society considers my diagnoses non-threatening, so I can pass for “normal” for long stretches of time. Many others have it much worse. Given all of that, Geel felt like a revelation to me.

The old hospital building is still there, on the large, leafy campus of Geel’s Openbaar Psychiatrisch Zorgcentrum, which is home to art studios, a centre for teens and children, and a modern in-patient psychiatric unit. There is a café in one of the newer buildings staffed by volunteers with a history of mental illness. The day I was there, a group of boarders and staff was assembling before leaving for a vacation in Spain. Everyone seemed to know each other, and over the sounds of suitcase wheels and spoons clinking against coffee cups were shouts wishing the travellers a good trip. If the scene was remarkable at all, it was only for its ordinariness.

Dymphna’s original church was destroyed in a 15th-century fire, but a new one was consecrated in 1532 and remains standing in spite of a tumultuous history. During the French Revolution, it was ransacked and used as a stable by French troops. The Battle of Geel, one of the bloodiest during the liberation of Belgium in the Second World War, destroyed its roof. But now it’s a peaceful place. What’s left of Dymphna’s remains are held in an ornate silver reliquary. In 2002, a local university tested them, and radiocarbon dating showed that they belong to a young woman who died between AD 700 and 800.

It’s tempting to view Dymphna through the lens of her saintly attributes — her piety, her self-sacrifice, her miracles. These are, after all, what set her apart from everyone else. But if the person described in her legend ever existed, she was a young woman who experienced horrors that young women are still confronting today. She was abused by someone she knew. Her abuser was protected by an imbalance of power and people who were afraid to challenge the status quo. She died at the point in the abuse cycle when the risk of violence is highest: the moment she gathered the courage to leave. Like so many other victims of abuse, Dymphna channelled her trauma into helping others. Her brief life was an act of determination, bravery and resilience.

Dymphna was someone who understood what it meant to recognize the humanity of those who weren’t accorded that basic right by the world around them. The family-care program isn’t miraculous; it is as profoundly human as Dymphna’s life story. It’s proof of how well we can love each other when we practise radical acceptance.

I still have my Dymphna medallion. I wore it in the months after I was hospitalized for depression in 2017 because it reminded me of how happy I’d been in New Orleans. It helped me believe in a future where I might feel that way again. I find comfort in rubbing it between my fingers or running it along its chain; each movement a tiny, wordless prayer.

I reached for it often when I was in Geel, a way of grounding myself when everything around me was so surreal. I didn’t know what to feel — sadness over the years of shame and stigmatization I’d felt over my mental health, frustration at the fact that the Geel model seems to be largely ignored by much of the world, or gratitude that I got to be there. I settled on a combination of all three.

On my last morning in Geel, I decided to go to the church one more time. Even though it was Saturday, the doors were open and the pews were full. It was, I realized, a confirmation ceremony for the congregation’s youth. I stood at the back and watched as a joyous priest doled out blessings, parents took pictures, and children chased each other up and down the aisles.

After a while, I went out to the small graveyard and sat in the grass. I could still hear the children’s laughter from inside the church as a family of rabbits started to come out, their noses twitching in my direction. I knew then that even if Dymphna’s death was brutal and lonely, her legacy is certainly full of hope and joy.

This feature was paid for through the David Wilson Broadview Fellowship, a reader-supported fund that honours this magazine’s former editor David Wilson and supports high-calibre journalism.

A touching read, and a beautiful story of acceptance and inclusiviness. Didn’t know about Dymphna, but her story certainly sounds familiar so many centuries after her death.

Here in California, if you feel the need to go see a psychiatrist, neurologist or therapist—you call the office make an appointment and pay for it. Seems much simpler than waiting for the government to approve.

Except what she’s talking about has nothing to do with who pays for it. She’s talking about how long it takes––in America, where I live; in Canada, where she lives; in Abu Dhabi, where I have lived; anywhere–to receive care. If you had ever faced this problem yourself you’d know that. Instead you take what could be an opportunity to learn something and turn it into your moment to make some narrow-minded political statement-that isn’t even relevant. I wonder…don’t you have a bridge to go hide under and collect tolls from people?

Only if you have insurance, can find a provider in your network, hopefully they are accepting new patients or you don’t have to make an appointment with a gp first before you can get a referral, and then wait upwards of a month or more for your first appointment. Much simpler.

Pretty obviously, if you can pay for it yourself, you can just call the office and make an appointment in any country of the world. There isn’t a law against paying for your own therapy in Canada or Europe or wherever. It’s when you can’t afford to pay that you need either the government or your insurer—whoever is paying—to approve it. In both cases, that can take time. It’s embarrassing that you’re expressing such ignorant opinions about this subject in public. Please don’t speak about important subjects if you don’t know anything about them.

If you can afford it, or if you can find one that takes medicare. Single-payer means you need treatment, you get treatment. I guess you haven’t noticed the many, many ill people living on the streets.

What a truly extraordinary story. Kudos to Anne Theriault. It reminds me of Jean Vanier’s L’Arche homes, which are, of course, much better known, and for people with developmental disabilities rather than mental illnesses, but the concept of “radical acceptance” is common to both models.

Thank you for making that connection. It is a rare that we hear of places that practice radical acceptance of those with mental illnesses whether they are considered minor or major. The issue is not one of payment but of the way people find their way back to normalcy through a different model that is not pathologized. It is a shame that most readers missed that point. I am so happy to have found this story. It is one of Hope at a time when it is in short supply.

What a needless comment about the Canadian healthcare system. One only needs to look at California’s homeless crisis to know that good mental healthcare belongs only to those privileged with money or insurance. So many are left behind.

Lt, I don’t understand how you can possibly defend the Canadian system of mental health. To compare it to what is happening in the U.S. is like comparing apples and oranges. Our system is far from just and very inaccessible to many in need.

Seen as victims of a cruel disease, our “other-minded” friends await our attentive love and support. How little we know about

the mysteries of the mind.

I used to work with a young woman from Geel, Belgium. I was curious where it was located and an internet search. Thru the search I found this article. I was fascinated by not over the history of the city of Geel, but with the catholic church. The incredible history of acceptance, love, and civic pride of the citizens taking into their homes- those with mental disorders. This is an excellent example of journalism at its best, highlighting humanity at its best. Should I ever am allowed to travel to Europe, I would like to visit Geel and my friend. FYI, she gives senior cats a home so that their final days are happy.

I am retired and funds are normally very tight. Otherwise I would gladly support this publication.

I have never heard of Geel before, which saddens me somewhat.

This was a captivating and profound read, uplifting and yet full of reminders of how abuse permeates our societies.

Very brave of Anne Thierault to share something so personal too, in such a tender way.

I have had the privilege of living in a small town, where a number of well-known and well-loved locals who were children in adult bodies were looked after by the community, given jobs by kind people and homes, and were safe after their parents and carers died. We learned not to be embarrassed when they called our names out noisily, but instead, to feel warm and grateful, because it meant we had earned a special place in their hearts.

A young man took up nighttime residence in my old car with a missing back window. He would get his daily medication in bubble wrap from the nearby Dispensary. When I went to a judge to get a restraining order, the judge proudly said that she had gotten him on the daily bubble wrap. I was so chagrined that I could not speak. Cleaning up the car, I would find bubble wraps with some pills untaken, and I would also find broken bongs. The ingestion of the pills should have been witnessed by the dispensary, not handed out in bubble wrap. The police said the man just moved from one property to another. I wrote the prescribing psychiatric person on the bubble wrap packaging and said what was going on. They found him a place to live because when I saw him on the sidewalk, he was cleaned up.

So pleased to learn about Geel from a brief mention in an article in the current London Review of Books. What a wonderful tradition left by St Dymphna!