The heat has already started to build by the time Ryan Sage rattles up to the lodge in the little white bus that is to take us into the heart of the Dreamtime, the ancient faith system of Aboriginal Australians.

It is not yet 8 in the morning, but Sage has already turned on the bus’s air conditioning, insurance against the scorching journey to come. Soon enough, he tells the passengers in his soft drawl, we’ll be glad for any cool air we can find.

I believe him. We are in Kakadu National Park, smack in the middle of the top lip of Australia. The equator is above us, the Tropic of Capricorn is below, and we are driving under a pitiless blue sky just a few dozen kilometres from the Indian Ocean.

Off in the distance, sunlight shimmers in the still waters of a billabong (a dead-end offshoot of a river), and beside the road, paperbark trees shed their skin. Blood-red termite mounds taller than me sprout like cathedral spires. Radioactive uranium ore lurks under the ruddy soil. Lethal saltwater crocodiles — “salties” — loll wherever there’s water. Kangaroos and their smaller cousins, wallaroos and wallabies, bound through the bush.

And hiding in the shaded underhangings of the ancient sandstone escarpment that juts across the landscape is one of the most extensive outdoor art galleries in the world: Kakadu’s rock paintings, both sacred and mundane. Kakadu alone features more than 5,000 documented sites of rock art, each containing multiple images, sometimes hundreds to a rock face, layered one on top of the other. Twice as many sites are thought to be tucked away in Kakadu’s hills, many locations known only to Indigenous Australians.

The rock paintings are much more than art. To Indigenous Australians, who arrived on this continent 65,000 years ago, some of the paintings depict ancestral beings that created the reality we see around us, manifestations of an Aboriginal faith system known in English as the Dreamtime or the Dreaming. The oldest painting still in existence, a charcoal design found just a few kilometres from where our bus is travelling, was drawn 28,000 years ago. Stonehenge, by comparison, began taking shape about 5,000 years ago. This means the Dreamtime is one of the oldest known religions.

But the rock art is not just the dusty archive of a primeval religion. It is part of an enigmatic, sophisticated animist faith that lives on. To many Aboriginal Australians, the stories the art tells are as relevant today as they were thousands of years ago. And that makes Australia’s rock paintings the text of the longest continuously practised religion on Earth.

When Indigenous Australians (a term that includes Aboriginal peoples and Torres Strait Islanders in the northeast) first came to this continent, at least three other humanoid cousins were still walking the Earth: Neanderthals, Denisovans and Homo floresiensis, also known as “the hobbits” for their short stature. Arriving in Australia, just about where Kakadu is now, was the final leg for one branch of the great human diaspora from Africa, a chancy experiment in survival. Yet, despite the difficulties of a new life here, it seems that creating this origin story was a first order of business. The question that bedevils me is why.

Maybe that’s why I have yearned to see Kakadu’s cache of rock art for as long as I can remember. Deep down, I’m hoping it will reveal what drives us to understand how the universe came to be. But maybe I’m also trying to figure out where I fit into the story of the universe. In my worst moments, I fear that the paintings will find me unworthy to read their secret code.

Ryan Sage has stopped at the Ubirr border store to pick up the last of the nine passengers who are joining today’s trek. I sidle out of the bus to look around and hit a wall of heat.

It’s dawning on me that I have badly miscalculated how hard it will be to see the rock paintings. Kakadu is a World Heritage Site. I had expected plentiful stores, hotels and transportation, a range of tour opportunities, hiking trails and informative signage at scores of sites. I had envisioned a red-soiled, subtropical Banff National Park. Not so. Kakadu is nearly two million hectares and, like most of the top end of the Australian continent, is a sparsely populated wilderness with limited facilities. Greyhound buses run to Kakadu only a few times a week. My “lodge” is really a campground outside the main town of Jabiru (pronounced Jab-ber-OO) with cabins and banks of high-ceilinged, bunker-style rooms (running water not included) for those without tents or caravans. The biffy is communal.

Only a small fraction of the paintings are available for public viewing. You have to know where they are, and you have to get permission to see most of them. Even then, not everyone is allowed to hear the stories the art is telling. Like the art, there are layers to the stories. Sometimes, there’s a public story, then another told to Indigenous Australians and then yet another told only to select Indigenous Australians who have the right to hear it. In these circles of knowledge, I am at the outermost orbit.

I had wanted to see something a bit off the beaten track. When I asked park officials about guided tours, they pointed me to Sage and the white bus.

Once he has all nine of us gathered at the border store, he looks us over. We are a young German couple with their two children, a couple from Sydney, a couple from Darwin (capital of the Northern Territory, a few hours’ drive away) and me. Smiling, he says that we are fit enough to see some of the harder-to-get-to rock paintings. To do that, we must cross the border from Kakadu into the even more remote Arnhem Land next door. Arnhem Land is owned by Indigenous Australians and is off-limits to outsiders unless they have permits. We can go because Sage’s company is owned by Indigenous Australians on whose lands the art lives, giving us permits by proxy.

The border is the East Alligator River. Tidal, it is navigable by Cahills Crossing, a narrow concrete causeway, but only when the tide is low. After that, the causeway floods, washing vehicles into the water. Four were swept away last year alone, Sage says.

It’s not just the flooding that makes Cahills Crossing one of the most dangerous roads in Australia. Throngs of massive and hungry crocodiles — not alligators, as the river’s name suggests — lie submerged, eyes just above the surface of the water. A few months ago, one killed a man who tried to walk across when the tide was high. A memorial bundle of flowers still hangs nearby. Sage informs us that a few weeks ago, a saltie propelled itself out of the water and just missed decapitating a woman who was netting a fish out of the water.

Sage has timed our journey precisely. The tide is rising, but the water is still low enough for us to drive through. On my left is a truck, upside down in the river. On my right, crocodiles. Sage estimates the largest of them is four-and-a-half metres long.

It’s a relief to get to the other side, into the forbidden Arnhem Land. The rock paintings we are about to see were made available to tourists’ eyes only a year ago. Perhaps 300 people a year get to see them, Sage tells us. I am conscious that we are among the chosen.

My need to see the rock paintings has become more urgent over the past two years. I have been immersed in the science of the universe’s origins, researching and writing a book about the Earth’s magnetic field. In fact, I’m finishing the final edit of the manuscript during this trip to Australia. My research has drawn me to some of the top universities in North America and Europe and through the 3,000-year arc of human scientific inquiry. It has taken me from the kinetic inner workings of the atom to the wild contortions of our planet’s molten core to the radioactive violence of outer space. I have travelled, metaphorically, from the distant beginnings of the universe into the Earth’s perilous future.

Of all those topics, the one that has fastened itself the most tenaciously to me is quantum field theory, physicists’ most up-to-date explanation of everything we see around us. It is the universe’s origin story, written in math. It has been difficult to grasp and, frankly, I’ve had a few false starts. In fact, when I began the book, I didn’t even know I needed to understand quantum field theory. But the more I immersed myself in explaining where magnetism comes from, the more I realized I needed the help of theoretical physicists. Their work is the most abstract of any scientists’ I’ve met. It is the most deeply imaginative. I have come to think of theoretical physicists as the poets of science.

Trying to describe the reality they see so clearly is fraught with possibilities for error. Basic scientific facts I learned in high school are no longer facts. Matter is made up only of the elements of the periodic table, like carbon, hydrogen and oxygen? No. The most basic parts of the atom are protons, neutrons and electrons? No.

Instead, as the theoretical physicist Sean Carroll of the California Institute of Technology explained to me, the stuff of the universe is fields. Not elements. Not atoms. By fields, he and other physicists mean fluid-like substances that ripple and fluctuate in waves or lines. Sometimes the fields get tied up into little bundles of energy to make particles like protons and neutrons, which form the nucleus of atoms.

We used to think that protons, neutrons and electrons were the basic building blocks of atoms. But it turns out that protons and neutrons are themselves made up of even smaller particles called quarks. We used to think that electrons moved about the nucleus of atoms in fixed orbits. They don’t; they move about the nucleus in orbitals, which are three-dimensional, mathematical expressions of where they probably are. You see what I mean about the level of abstraction.

The bottom line for us mortals in this difficult-to-grasp science is that the stuff we see around us — my arm, my desk, the computer I’m writing on, the red cardinal perched on the garage roof in my backyard, the planet, the sun and the stars — is made up of fields, waving through the universe. The fields are connected. So in a completely literal sense, we are all connected to each other because we are part of the same fields. We are connected to every stone, every creature, every cloud, every galaxy. And not just connected. We are the same stuff.

Not only that, but what we see is only a tiny bit of what’s actually there. Invisible forces fill up what scientists used to think of as empty space. Empty space — even a vacuum — is full of fields that are constantly on the move.

One way I began to describe it to myself was through a simple experiment. A bar magnet has a north pole and a south pole. If you take two magnets and try to put two norths or two souths together, the magnetic field between them pushes them apart. That is tangible evidence of the invisible, inescapable fields that surround us. When you play with those magnets, you are playing with the universe.

I had muddled through all this for my book, but I was still having trouble explaining the timeline of how these fields came to be. So I emailed Carroll and asked: “At what point in the birth of the universe did the fields and particles show up?” It seemed a logical question. He wrote back: “The fields and particles didn’t show up. They were always there. Fields are what the universe is made of.”

My world shifted.

And for some reason, that sent me straight to Kakadu.

We are climbing in the heat. Sage, in his navy blue shorts, long-sleeved safari shirt and wide-brimmed bush hat, is leading the charge. Just as he didn’t mention Cahills Crossing until we were on it, he has cannily not told us how far we have to climb. Instead, he has distributed among us some of the paraphernalia for our eventual tea time — cookies, cups, Thermoses, a tablecloth — and has set off, carrying the biggest load of supplies himself.

The sandstone, laid down about 1.6 billion years ago, makes natural steps. As you look up, it’s like seeing stacks of vast reddish plates reaching into the cloudless blue sky. Gnarled nests of roots, fired by the heat into brittle bones, grab at our ankles.

We pass a curved line of carefully placed small sandstone rocks. Sage says that not even the local Indigenous Australians, or traditional owners as they’re sometimes called, know why these are here. It’s hard to discern a pattern, except that the stones are running somewhere, maybe pointing to something. I can’t help thinking about field lines, physics. Much of the surrounding sandstone is stained black from the buildup of algae over the eons. But underneath the line of small rocks, there’s no black, and that means the rocks have been here undisturbed for a long time. We are looking at antiquity, Sage tells us.

We keep climbing in the direction the stones are pointing, around a corner, and then Sage stops short. He points into the distance. It’s a male black wallaroo — larger than a wallaby but smaller than an average kangaroo. It’s believed that fewer than 10,000 adult black wallaroos still survive; the International Union for Conservation of Nature, which tracks threatened species, puts them at “near threatened.” They live only in Kakadu and the western part of Arnhem Land.

Against the stark shadows the sun casts on the cliffs, this wallaroo is nearly indiscernible at first, but gradually it comes into focus. Big-footed, it hops leisurely from one rock shelf to another, long tail curved behind it as a counterweight, stopping to graze in the cool of the shadows. It’s a favourite meat of local Indigenous Australians, and Sage swears us to secrecy. If we tell anyone we saw it up here, they’ll send a hunting party.

After that, it’s up yet more thigh-crunching sandstone steps and around another corner, and then we see, right there in front of us, a magnificent gallery of rock paintings, tucked away in the shade of a shelter in the cliff. It’s as if some of the reddish sandstone plates had fallen out to make a gash a little taller than we are, narrowing to a tiny wedge at the back. We head for it gratefully, a small respite from the sun.

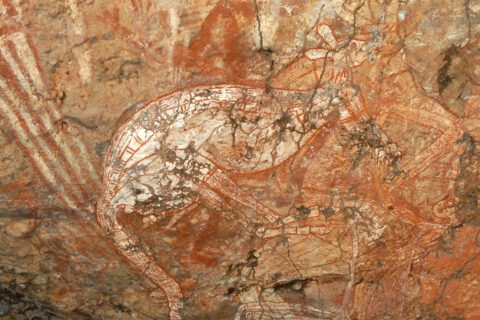

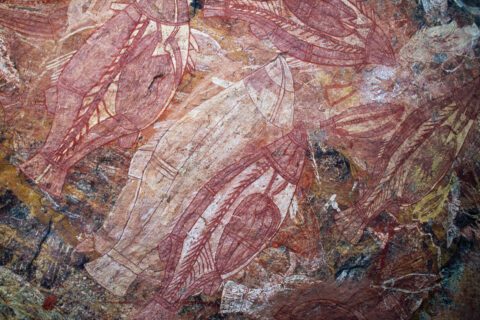

Every surface is densely covered with pigment. Layers on top of layers. Most depict animals drawn in such precise detail that they could be used in wildlife textbooks. There are lots of barramundi, a staple fish of this region, with their characteristic upturned bottom lips, painted in white pipeclay over red ochre. These are the colours of the earth, fixed with blood or sap or egg yolks, soaked into the stone. You can see inside the fish to their skeletal structure, as if with X-ray vision. There’s an enormous crocodile crawling over the underside of the shelter’s ceiling, and other fish in orange and yellow.

It’s hard to take everything in, harder still to know what each animal is. Sage, whose late grandmother was an Indigenous Australian and who has long been a student of rock paintings, says he can name every species he sees. But to me, the overwhelming sensation is not the individual creatures or the meaning of each one but the riot of life and colour.

Suddenly I see the negative of a left hand, fingers splayed, outlined in white against the ochre, and I’m staggered by the image playing out in my head. Someone, hundreds or perhaps thousands of years ago, put a hand there, blew white paint at it and left this mark. How did Indigenous Australians learn to survive in these harsh landscapes, much less paint their faith on the rocks?

Around the corner, in a shelter so cramped only a few of us can view it at a time, is a starkly different image. It is a dark line of tiny mimih, or spirit figures, according to Northern Territory’s Aboriginal Australians.

These mimih are — all too obviously — male. They wear headdresses and are throwing spears and boomerangs, gathered along a curving line of dots, much like the ones we saw when we began to climb. The frieze has been carbon dated to at least 9,500 years ago.

Aboriginal Australians here believe that the mimih still live in the cracks of the rocks. Fragile, they emerge only on still days for fear the winds will snap their necks. Aboriginal Australians also believe that mimih did these self-portraits and thus taught humans how to paint. And it’s the act of painting, rather than the images themselves, that carries metaphysical and spiritual weight, Sage explains. Rock art is a byproduct of the faith.

Many Australians still describe key dates in the continent’s history as “B.C.” or “A.C.,” meaning before (Captain James) Cook arrived or after. Cook claimed Australia’s east coast for Britain in 1770; by 1788, ships full of convicts were arriving to set up homes. The British long asserted that Australia belonged to nobody until they got there; it was terra nullius. No Indigenous peoples of Australia were seen as landowners until 1976, when the federal government recognized Indigenous land rights in parts of the Northern Territory, including Arnhem Land. It wasn’t until 1992 that a landmark court ruling — the “Mabo” decision, named after Indigenous land-rights advocate Eddie Mabo — established that all Indigenous Australians could have traditional rights to their land.

With a few exceptions, Indigenous Australians were not allowed to vote in federal elections until 1962. They were not counted in the country’s official population until 1967. They still have no special protection under the Australian constitution.

Christian missionaries dispatched to the colony ran roughshod over the ancient faith system. Indigenous art was viewed as primitive scratchings. Sacred objects were often shown in natural history museums alongside flora and fauna specimens, if they were shown at all.

“Nineteenth-century attitudes placed Aboriginal Australians on the lowest rung of the evolutionary ladder, and they were regarded as a people without art,” writes Wally Caruana, an eminent Australian art curator and author of the definitive textbook, Aboriginal Art, now in its third edition.

In fact, even though Indigenous Australian artwork goes back tens of thousands of years, it was the last great body of art in the world to be recognized, says Caruana. It barely made a ripple on the international art scene until the middle of the 20th century.

Now it hangs in prestigious art galleries around the world, including in a place of honour in the Art Gallery of New South Wales in Sydney. And even as non-Indigenous people have been itching to understand what the art means, Indigenous Australians have been both exquisitely generous with some explanations and fiercely protective of the need to keep other stories private.

The fundamental idea, Caruana writes, is that art represents not only the spiritual life, but also the natural and moral order of the cosmos. Each Aboriginal Australian inherits direct and indirect rights and responsibilities to specific bits of the land, as well as rights to parts of the ceremonies. They also inherit rights to Dreamings and connections to some of the ancestral and supernatural beings that created everything in the first place.

Making art matters so much to Indigenous Australians because they believe their ancestors created reality as they moved through it, explains Bethune Carmichael, a PhD candidate at Australian National University in Canberra and a specialist in rock art. Often, those ancestors became a recognizable feature of what they created, or turned into an animal that had adventures and then became the landscape: that cliff is an ancestor, and so is that creek. Great, totemic ancestors — for example, Rainbow Serpents, the giant lizard Perentie, the Wagilag Sisters and the Lightning Brothers — and the heroic stories of their adventures are enduring motifs in the art.

The whole of Australia, which is to say, the universe, was created from these Dreamings and is now made up of them. That means looking at the Dreamtime rock paintings is like watching the big bang happening.

It’s not just images and stories, but also dance and songlines. Indigenous Australians own rights to different parts of songlines, which are linked to different parts of the land. In fact, the songs are a sophisticated memory tool to help people know where to find the next shelter or stash of drinkable water as they navigate the unforgiving landscape. In ancient times when people didn’t write down language, learning a songline was learning to survive: in a most basic sense, one’s faith was one’s survival.

As Indigenous Australians sing and paint and dance and perform ceremonies, they keep reality going; as Caruana puts it, they keep their part of a contract that lets humanity be at peace with the universe. This means creation must keep on being created. Unlike the Book of Genesis, it is not a one-time deal.

To create ritual art, each person with direct rights to an image must work along with one who has indirect rights, Caruana explains. It’s a grand and complex marriage of interests, an acknowledgment that we are all dependent on one another and that only together can people connect with the power of the ancestral beings and keep the world on track. To someone like me, trained in evolutionary theory and the theory of biological diversity, this makes perfect sense.

But trying to describe all of this is as fraught with peril as delving into quantum field theory. Apart from the complexity of the belief system, it’s also hard to know who has the right to tell the stories, to explain the fundamentals, and in what detail. An effort by the Australian National University and the South Australian Museum in Adelaide to mount a show featuring a songline about the Ngintaka Dreaming from the Anangu Pitjantjatjara Yankunytjatjara Lands in the northwest of South Australia triggered a controversy a few years ago when some traditional owners asserted that their stories should not be made public — this despite the researchers having collaborated with the Anangu people for years and getting support and permission from many of them to tell the stories. The show eventually went ahead.

We are heading back to Kakadu in our little bus, exhausted from the heat. The air conditioning is on full blast, and it’s not enough.

Sage points to a big jut of sandstone in the distance and starts to tell us a story as he drives. His voice takes on an incantatory quality. Before there was life on Earth, he says, it was plain, flat, featureless. Then the ancestors came to the land. One of them was Yingana, who carried many dilly bags, which are woven from plants and used to gather food. She came from the north on a paperbark raft over rough seas, and she waited and waited for the seas to recede. After they did, she planted her dilly bags in the ground. Out of them came language, laws, people, plants and animals and everything needed for life.

That black rock, standing at a 45-degree angle in the distance, is where she began and therefore where life started. And up on that rock, Sage has heard, there is more rock painting. It’s a very sacred site. He has never been there.

It’s obvious that none of us on the bus will be allowed to go there either. We are here as visitors, travelling in our white bus, circling in an orbital around the nucleus of this complex culture. Despite the marvels we’ve seen, we have barely scratched its surface. In fact, we’ve not been allowed to see any of the important spiritual works. What we have seen is workaday, compared to what else is hidden in the rocks. But it occurs to me that if I were Indigenous Australian, I might want to keep these ancient secrets safe, too.

Later that evening, at the outdoor restaurant of my “lodge,” I’m trying to put all these pieces together. I’m drinking a gin and tonic, a sop to the extreme heat. To get the cocktail, I had to present a card to the bartender verifying my credentials as a campground guest. In Kakadu, drinking is strictly limited to outsiders who pay to stay here. Behind me, two young Indigenous Australian men are playing billiards, smoking but conspicuously not drinking alcohol.

As I sip, I am rereading The Songlines by the British travel writer and novelist Bruce Chatwin. Much lauded when it came out in 1987, two years before his death, it was one of the first works to explain the Indigenous Australian faith system to the larger world. Based on two brief trips Chatwin made to Australia, the book was a hybrid of fact and invention. “To call it fiction isn’t strictly true, but to call it non-fiction is an absolute lie,” he told an interviewer.

For all the brilliance of the writing, the book’s reputation has suffered in recent years. The critique is that Chatwin mainly talked to other white people about Indigenous Australians and misrepresented Indigenous Australians’ beliefs.

It’s hitting home. I’ve found it impossible so far to speak with an Indigenous Australian expert about the Dreamtime. I spent part of an afternoon with Indigenous Australian artists as they worked at the Injalak arts centre in Arnhem Land’s Gunbalanya community. But no one seemed inclined to talk to me. I was reduced to reading some plaques on the wall about the meaning of rock art.

My last hope for enlightenment is Maningrida, a community yet deeper into Arnhem Land. Bethune Carmichael tells me that Indigenous Australians there are extremely concerned about protecting the rock art from floods, the result of climate change. I hope they will be able to talk to me about why the art matters to them. I have a plane ticket to deliver me there in 36 hours.

I’m a little on edge because, as a journalist who is not an Indigenous Australian, I need a special permit to enter Arnhem Land without a guided tour. I’ve been assured I can get one. But I don’t have it yet. And, despite repeated emails and innumerable calls on pay phones, I haven’t been able to reach the person who can give it to me.

The next day, I hoist my bags onto my shoulders and make the blistering walk into Jabiru to catch the Greyhound bus back to Darwin. That night, increasingly frantic emails and phone calls. My flight from the Darwin airport is at 8:05 tomorrow morning, and I still don’t have a permit to land in Maningrida.

Finally, the email I’ve been waiting for shows up in my inbox. I cannot get a permit in time. Therefore, I cannot take the flight. Nor can I talk to the Indigenous Australian custodians in Maningrida about the rock art. I will never get any closer to understanding the Dreamtime than I am right now.

I take a nighttime walk around Darwin, drawn by the raucous arts festival that’s been going on here for a couple of weeks. At the festival site, music blares from vast tents set up in carefully tended public spaces. Open-air stalls feature wood-fired pizzas and glasses of wine. The joy is palpable, and so is the wealth.

Few Indigenous Australians are here at the festival site. Instead, as has happened every night I’ve been in Darwin, many who have travelled into the city from Kakadu and Arnhem Land are gathered a few blocks away near a downtown mall, preparing to sleep on the streets. The divide between the keepers of this ancient faith system and others of our species is wide and persistent.

I’m deep in thought. I’ve been exploring one of the most ancient explanations of the birth of the universe, as well as the most recent. And I’m astonished at how much they overlap. To Indigenous Australians, the ancestral beings create reality. To theoretical physicists, the field lines create reality. The universe is the stories; the universe is the fields. It is a continuous process of creation, no matter which of these two ways you cut it. It’s going on around us even now.

My thoughts drift back to the two years I’ve spent diving down the rabbit holes of quantum field theory and to the decades I’ve been obsessed with the Dreamtime. Both quests began with my need to better understand the beginnings of things. It dawns on me tonight that even after talking to some of the world’s best academic minds, I might never entirely comprehend either of these two origin stories. Both stories are too ancient and too sophisticated for me to fully unravel. The layers of abstraction are too dense.

It is immensely humbling for a reporter who has spent a lifetime believing that if I only researched deeply enough, if I only bore witness faithfully enough, I would be able to get to the core of essential truths.

But what I do understand more clearly than ever is this: whether we are Indigenous people living an ancient narrative or researchers probing strange new frontiers, we will never stop trying to figure out our place in the universe. It’s just who we are. And maybe that’s enough.

This story originally appeared in the January 2018 issue of The Observer with the title “In the beginning.”