For every Christian, the answer to the question “Does Jesus love me?” must be an unequivocal yes. That’s the short answer, and the simple answer. But few things in life are all that short, and almost nothing worthwhile is simple — especially when it comes to questions of faith. It’s actually a bit of a puzzle as to why so many folks expect simplicity in faith when most of us know in our hearts that reality is always complex and that human beings are complicated beyond measure.

As to Jesus’ love, that is a question of near ultimate significance, and one that requires nuanced thought.

You may unsubscribe from any of our newsletters at any time.

My first theology was absorbed through children’s hymns, including “Jesus loves me, this I know . . .” At first it was “for the Bible tells me so.” With the advent of the New Curriculum, a 1960s revamping of the way in which the Bible was taught in United churches, the lyrics were updated to “and the Bible tells me so.” The change is important: the latter formulation acknowledges that despite the centrality of the scriptures to Christian faith, the believer is informed equally by the tradition and community of the faithful and by the movement of the Holy Spirit.

Either way, the conviction is that Jesus loves us and sustains many of us. And no doubt, when my eyes come to close at last on the wonderful yet ultimately wearying world, it will be the devotional theology of hymnody that sings me to sleep, and not the erudition of ecclesiological doctrine.

More on Broadview:

-

We used an AI chatbot to speak to ‘Jesus’ about the climate crisis, miracles and Christmas

- What if God is human too?

And yet, it remains misleading to say “Jesus loves me.” For if we are speaking of Jesus of Nazareth, the itinerant carpenter and rabbi who lived, healed, taught and died in first-century Judea, when Pilate was procurator and Tiberius was emperor, then, not to be coy, that Jesus doesn’t know anything about you.

If the Jesus of history did, then the Incarnation would make no sense at all.

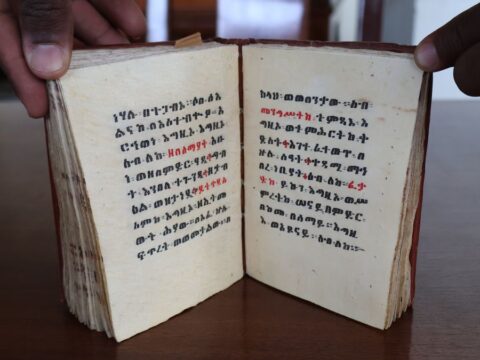

I love the Gospels, all four of them. I love Mark’s unrelenting focus on the political urgency of the Kingdom of God; the first-century Jewish riff in Matthew; the Gospel spin for the gentile world in Luke; and the elegant theologizing of John. But for Christology, the earliest and most serious work is in Paul’s letters, and of Paul’s Christology, the best and earliest is in Philippians 2:5-7: “Christ Jesus . . . though he was in the form of God, did not regard equality with God as something to be exploited, but emptied himself, taking the form of a slave, being born in human likeness.”

The Very Rev. Bill Phipps captured that Christology — in the theology biz we call it “kenotic,” literally “poured out” Christology — in a conversation I had with him in 1997. “In Jesus,” he said, “we find all of God that can be contained in a human being.”

And there’s the heart of the matter: all of God that can be contained in a human being. That’s what the Incarnation means. Jesus of Nazareth was a human being. He had to be; else nothing wonderful could come of God’s actions in him.

By definition, the Jesus into whom the Spirit of God was so lavishly poured had to accept the limitations of time and space to which all humanity is subject. He grew hungry, thirsty, weary and footsore. He had moments of impatience. He lacked anything like omniscience: when a woman in the press of a crowd sought an anonymous healing from him, he asked who had touched him. He had moments of appalling loneliness and despair: in the Garden of Gethsemane, he asked that the bitter cup of crucifixion might pass him by; from the cross, he cried aloud that God had abandoned him.

All of this, it seems, was to ensure that God would know us in an entirely new way, not simply as creator to creature, but as parent to child.

All of this, it seems, was to assure us that God loves us; loves us to the greatest depths imaginable.

God in the carpenter of Nazareth dies on the cross. The carpenter of Nazareth who is in God is raised on the third day.

Jesus, the carpenter of Nazareth, didn’t have the chance to make your acquaintance. The Risen Christ knows you intimately, and loves you, just as God loves you.

Of course, in the end, this is theological discourse.

Does Jesus the Risen Christ love me, love you? If you get to know him, you’ll have a better idea. That’s where scripture, prayer, community and communion come in. You won’t be disappointed.

***

Rev. James Christie is a professor of ecumenism and dialogue theology at the University of Winnipeg.

As the Creed of Nicaea and the Chalcedonian Creed state (along with other creeds): “One and the Same Christ, Son, Lord, Only-begotten; acknowledged in Two Natures unconfusedly, unchangeably, indivisibly, inseparably; the difference of the Natures being in no way removed because of the Union, but rather the properties of each Nature being preserved, and (both) concurring into One Person and One Hypostasis; not as though He was parted or divided into Two Persons, but One and the Self-same Son and Only-begotten God, Word, Lord, Jesus Christ; even as from the beginning the prophets have taught concerning Him, and as the Lord Jesus Christ Himself hath taught us, and as the Symbol of the Fathers hath handed down to us.” (T. Herbert Bindley 1899)

We cannot emphasis Christ’s humanity over His Deity as suggested.