It’s difficult for Mark Covington to hide. Sometimes, when he works inside, he’ll leave his truck at home so that no one knows he’s in. Otherwise the knocks just keep coming, and it’s impossible to get anything done. That’s not an option outside, though, where he spends much of his time working at the Georgia Street Community Garden. Still, on a June morning, it’s easy to see why he might need cover to get things done. Some teenage girls scurry by, saying a quick hello between giggles. There’s a woman on a motorbike who waves and another in a car who honks her horn. Two young boys walk up, one counting his steps to 100 as his mother shares news of his brother’s recent report card. At the centre of it all is Covington.

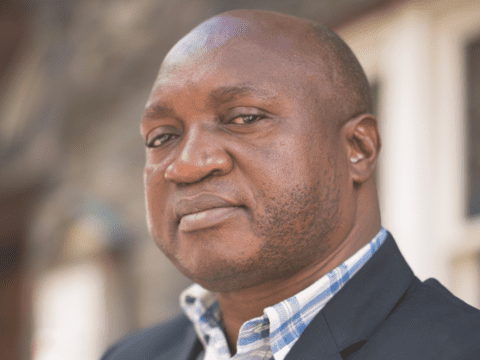

A big man at six foot two and 340 pounds, the 39-year-old Covington is soft-spoken and polite, the kind of guy who’s not likely to toot his own horn. Here in Detroit, though — especially in the Georgia Street neighbourhood he calls home — he’s something of a celebrity, a community activist who has trouble calling himself that. Yet he’s been featured in the Guardian, was photographed for Time magazine and appeared in a music video for the British band Above & Beyond’s song On a Good Day.

You may unsubscribe from any of our newsletters at any time.

If Covington were to count his own steps, ending where he is today, his first would have been in 2008 when, after three years in Taylor, Mich., he lost his job as an environmental technician and had to return to the Detroit community where he grew up, to live with his mother. It was then that he took a walk through the neighbourhood and saw what had happened while he was gone. Not just the empty lots left to languish, the grass growing waist high and homes abandoned. Although there may have been more decay, it wasn’t exactly new — like much of Detroit, the neighbourhood had been deteriorating for years. It was the garbage that bothered him: litter clogging the gutters so that the freshly melted snow couldn’t drain, old rubber tubing (the copper wiring removed and sold for scrap metal) thrown aside, and even mail from as far off as the suburbs discarded in those old lots as if Covington’s childhood neighbourhood was nothing more than a garbage dump.

Covington just wanted to stop the dumping, to repurpose those empty lots (most now city owned). He came up with a plan: “I figured if I put a couple rows of vegetables or some flowers out there, people would stop dumping,” he says.

Today, anyone can pick from the garden he created.

Urban farming is becoming popular throughout Detroit, as communities try to take their city back. And like the story of Covington’s neighbourhood, the story of Detroit’s urban agricultural movement is about more than just fruits and vegetables. It’s a story that cities in Canada and around the world may be able to learn from, too: a tale of rebirth in action, of industrious people and communities standing up for themselves to turn their city around — creating solutions where there were none. For many Detroiters, it’s also a sign of things to come.

“Failure is simply the opportunity to begin again, this time more intelligently,” Henry Ford once said. Back when Ford was still alive, though, Detroit had no need for new beginnings. It was a hub of industry, the place workers went looking for jobs. Even before the Ford Motor Company was established in 1903, Detroit was a thriving ship- and railcar-building town. Thereafter, for better or worse, it was Motor City. But in the 1950s, an exodus to the suburbs began, as Detroiters sought out the picket-fence existence.

That, says Toby Barlow, was what you did when you were successful. “I have a well-recorded theory about what happened to Detroit, which is that everybody won,” says the op-ed contributor for the New York Times. “Detroit is probably the greatest, most victorious city since ancient Rome.”

Yet in 2008, Detroit took the top spot in Forbes’s inaugural list of the most miserable cities in America; at the time, it had the highest rate of violent crimes and the second-highest unemployment rate in the United States, as the recession hit and the American automobile industry suffered. The city’s population, which peaked at about two million in the 1950s, fell to 714,000 by 2010. Today, abandoned homes and buildings punctuate the landscape. Detroit is clearly a city in need of reinvention.

For Barlow — author and adman — the urban farming movement plays an important role in that rebirth. He moved to the city five years ago, just before his first novel came out. Talking to the press about the book, he found himself defending the city he’d moved to; now he shares Detroit’s story in the Times. Maybe it’s not surprising that the ad executive — whose day job is working at the ad agency Team Detroit on marketing campaigns for Ford — thinks a new brand, or a new narrative, for Detroit is in order. He’s seeing those stories in a growing arts movement and a burgeoning small business community, but they haven’t captured the world’s imagination yet. “Ultimately, you hope for a great breakout story of some sort. You hope for some great movement, some great energy,” he says.

Detroit’s urban agriculture movement seems to be that story. And not only because it fits into an international discussion — a modern movement toward local food and urban farming in general — or because the contrast of agriculture and industry makes it all the more interesting. It’s also engaging because it’s the story of Detroiters using the city’s liabilities — the vacant lots and abandoned homes — to create assets: somewhere to plant.

Or so says Mike Score, president of Hantz Farms and former agriculture educator at Michigan State University. Aspiring to become the largest urban farm in the world, Hantz Farms — still waiting for final approvals — has plans to turn hundreds of acres in Detroit into farmland, with a research facility dedicated to furthering knowledge about urban agriculture. The plan, says Score, would provide jobs, beautify the city and create a hub for urban agriculture.

“The world population is expanding toward nine billion, and fuel costs are increasing,” he says. “Somehow, cities are going to have to learn to integrate farms within urban centres….And when leaders from different global cities have talked about the need for a canvas of sorts where research and development can take place, most other global cities aren’t as well suited for this type of venture as Detroit is.”

Hantz Farms is by far the largest venture in the Detroit urban agriculture movement, which is mainly made up of smaller gardens. How many exactly is unknown, but the Garden Resource Program, a city-wide initiative designed to pass knowledge and resources on to Detroit’s network of gardens, assists about 1,600 growers. These gardens collectively produce thousands of pounds of food.

And in a city without a major grocery chain — where families sometimes buy their food in gas stations and the obesity rate, at 70 percent, is one of the highest in the United States — urban agriculture isn’t just about reclaiming the city. It’s a way to support community, too. Sometimes that means growing food to sell at local farmers markets or the popular Eastern Market, where up to 40,000 people shop every Saturday. Other gardens use Covington’s model, allowing anyone to pick for free as needed.

Earthworks Urban Farm, another community garden (with historical ties to the local Capuchin Monastery), grows food to supply its soup kitchen, where locals in need can come and get a meal. They also have youth programs and agricultural training programs to pass on gardening knowledge. For them, urban farming is a form of activism. “It’s an act of creating your own independence from a system that we relied on for so long to provide for our own basic needs….Those jobs that we depended on, those businesses that we depended on for our tax base, they’re not there any longer,” says Earthworks out-reach co-ordinator Shane Bernardo.

If you ask Bernardo why Detroit is uniquely suited for urban agriculture, it isn’t the available land — the empty city lots — that he mentions first. Rather, it’s the people and the “history of our resiliency and our toughness, and our blue-collar attitude,” he says. “We’ve been able to realize forms of being self-sufficient.”

Writer Barlow agrees: Detroiters themselves are an important component in the whole equation. There’s a sense these days, he says, that someone can start something and it will succeed. That doesn’t mean, he adds, that there won’t be differences of opinion. In fact, there already have been. Some community gardeners don’t see a place for a large-scale Hantz Farms model, for example, and there have been instances of local entrepreneurs trying to buy city lots to expand their small businesses only to find themselves challenged by community members who use that land to garden. But that kind of dialogue is part of a healthy urban environment, says Barlow. “As the city begins to succeed, there are going to be some really interesting and hard dilemmas that we’re going to face that every successful city faces. But we can’t really be afraid of that.”

City expert Jino Distasio, director of the Institute of Urban Studies at the University of Winnipeg, compares the current situation in Detroit to revitalizing a city after a natural disaster like Hurricane Katrina. Canadian cities are not immune to the forces that have laid waste to Detroit, but on the whole, he notes, they have not suffered on the same scale. “In the Canadian context, we haven’t had the same level of industrial abandonment or industrial restructuring as we’ve seen in these real rust-belt cities of the U.S., these industrial places,” he says.

Still, that doesn’t mean Canadian cities can’t learn from Detroit. The best new beginnings often “percolate up from the grassroots,” Distasio says — and Motor City is demonstrating that now. With enough momentum, he suggests, groups of people like those behind the urban gardens may be Detroit’s salvation. “They just want their community to be a good place to live,” he says. “Creating good, positive environments and good, positive neighbourhoods starts with mobilizing local people.”

When it comes to Detroit specifically, maybe another quote is apt, a Winston Churchill quote that Barlow cites: “You can always count on Americans to do the right thing — after they’ve tried everything else.” That, says Barlow, is the crux of what’s happening there today.

“We were hoping for the wrong solutions for a long time. We were hoping for saviours. We were hoping for big-box solutions. We were hoping for a major corporation to come and relocate here,” he says. “We thought that X, Y or Z [would help], and at the end of the day, the city has realized that what we really need to do is work together. I think there’s a collective sense that the time has come for lots and lots of small solutions.”

On a Georgia Street, Covington picks the odd weed growing between the vegetables as his neighbours filter by. The 18 lots he gardens and maintains are just the start. Through donations, he’s been able to create a community centre for the neighbourhood and is working on installing a library/computer lab, both in repurposed abandoned buildings. He runs weekly movie nights, has a holiday dinner for the community every year and gives away school supplies come August.

There are still other abandoned homes in the neighbourhood, just as there are overgrown empty lots. But Covington says that petty crime in the community — mostly windows smashed by bored kids — is down. People have gone elsewhere to dump their garbage, too.

Covington’s plan, it seems, is working. “My saying is, one house, one block, one neighbourhood at a time,” he says.

***

This story first appeared in The United Church Observer’s September 2011 issue with the title “Planting a better future.”