Clifford Mushquash is a delegate at COP27, the United Nations climate conference in Sharm el-Sheikh, Egypt, which runs from Nov 6-18. He is Anishinaabe from Pawgwasheeng (Pays Plat First Nation), and a registered social worker studying for a masters of public health at Lakehead University in Thunder Bay, Ont., with a specialization in Indigenous and northern health.

Mushquash joined the international event as part of a delegation from KAIROS and For the Love of Creation. He is also a facilitator of the KAIROS blanket exercise, a popular workshop that aims to share the story of Canada from an Indigenous perspective.

You may unsubscribe from any of our newsletters at any time.

He spoke with digital editor Emma Prestwich on Thursday from Egypt.

Emma Prestwich: What has your experience of the conference been?

Clifford Mushquash: I had this realization tonight that environmental issues and climate justice are so much more complex and nuanced than just the environment and politics. It’s complex financial systems, it’s women’s rights, it’s minority rights, it’s Indigenous rights. It’s the role of 2SLGBTQ+ and gender-diverse rights. It’s complicated by ongoing colonization and occupation in some parts. There’s a woman in our delegation who is from Palestine, and I’ve had really wonderful conversations with her this week. Palestine, like many regions, is adversely affected by the climate emergency where it doesn’t contribute as much to the climate crisis even though it experiences the adverse effects of it.

We’ve heard about the role of women in climate action and how women are adversely affected and more affected by the climate crisis in certain parts of the world. It’s more than just the environment, it’s more than just emissions, right? It’s so layered and so nuanced.

It’s been challenging for me in terms of wrapping my head around all of that, because I don’t centre myself as an environmentalist or as an environmental advocate or warrior. My people’s understanding of health is holistic and all-encompassing. So that includes the physical and the biomedical, but also the mental and the spiritual. But it also extends to land and how we relate to land and water.

EP: Can you speak more about how you see health and the environment intertwine?

CM: For the Anishinaabe, we are the land and water and the land and water is us. So what we do to ourselves, to our bodies, we do to the land and water and what we do to the land and water, we do to ourselves. And so it was inspiring to hear First Nations people from Canada here talking about that as well. That’s how I understand myself. And that’s how I’m more deeply understanding myself now.

I wasn’t raised in my culture. My father is First Nations. My mother is Italian and Ukrainian. As I got older, I started connecting to my culture more through a number of different avenues. And as I understand it, I am the land and the land is me. And so when we talk about the climate crisis and the land hurting, our people are also hurting and our people need healing as much as the land needs healing. And so because we’re all interconnected, when we heal one, we’ll heal the other.

EP: You facilitated one blanket exercise while you were here. Tell me about that.

CM: Anytime I’m able to offer the exercise, however big or however small it is, is a win for me. Because anytime I can share the story of Turtle Island and the consequences of that story, anytime I can share that with one person or hundreds of people, is a good thing, because that’s that many more people that have heard the truth.

About 20 people participated, which is about the average size that I typically get for an exercise. I think the global community over the last few years have become more aware of things that have happened [in Canada]. A number of the individuals were from outside of Canada, and so a lot of them spoke about how colonization has affected their land and their people and themselves. There’s a comfort in that, because it’s a shared experience, even though the nuances are the variable.

We had people from Africa talk about the transatlantic slave trade and how they weren’t dispossessed of their land so much as the land was dispossessed of their people. So they were removed from their land, but their land was removed of its people. And that’s different than the case of Turtle Island. Because we were shuffled around within our own territory; we weren’t picked up and brought somewhere else.

More on Broadview:

- Can the courts save us from the climate crisis?

- Advocate shocked by racist backlash over Indigenous food forest in Vancouver

- Giving land back and other ways Canadians are making reconciliation personal

EP: Is there a message that you were able to communicate at the higher level or you wish you were able to communicate to some of the decision makers at this event?

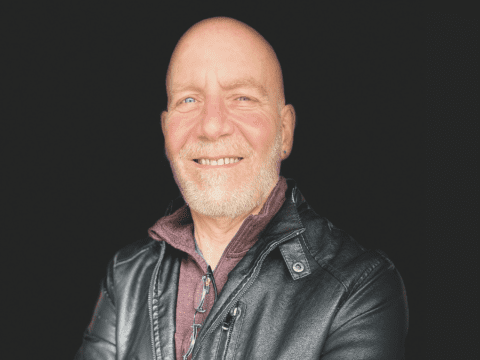

CM: I had the opportunity to speak individually with two Members of Parliament. [One is Alexandre Boulerice], a Member of Parliament for Rosemont—La Petite-Patrie in Quebec and the deputy leader of the New Democratic Party. So I spoke to him following an event in the Canada Pavilion that he was on the panel for, and I also spoke with Mike Morrice, the Member of Parliament for Kitchener Centre. He’s a Green Party MP.

In our culture, when we ask something of somebody, we offer tobacco. We pray with that tobacco, and we offer it from our left hand, because the left is closest to the heart. And when you receive a gift, you receive with your left hand again, because it’s closest to your heart. I had asked both of them to take time with that tobacco, to pray and reflect on their relationship with land and water.

And I challenged them to see themselves as part of the land and water, and to also encourage their colleagues in the House of Commons to do the same. Because if we’re going to reconcile in Canada, we can’t reconcile by using the same system and structures that we always have. We can’t sit down for dinner with the table set the same way it has always been set. We have to reset that table.

To do that, non-Indigenous people have to learn from Indigenous people and try to understand themselves in the way Indigenous people do. When it comes to the environment, that would be non-Indigenous people seeing themselves as part of the land and water. And so when we see ourselves as part of land and water, would we still be developing oil and gas and building pipelines? Would we still be using nuclear power and burying nuclear waste in the earth? Would we still be polluting waters? Would we still be fighting land defenders in Wet’suwet’en territory?

***

This interview has been edited for length and clarity.

Emma Prestwich is Broadview’s digital editor.