It’s not that I don’t value civility. I do. And yet as we grapple with all the wrongs we see here in Canada — the genocide wrought on Indigenous peoples laid bare in all those unmarked graves! – I wonder if we’re honest about what our politeness really is.

“Polite” comes from the Latin word politus, which means polished. Originally, that meant polished like a stone to a high gloss.

You may unsubscribe from any of our newsletters at any time.

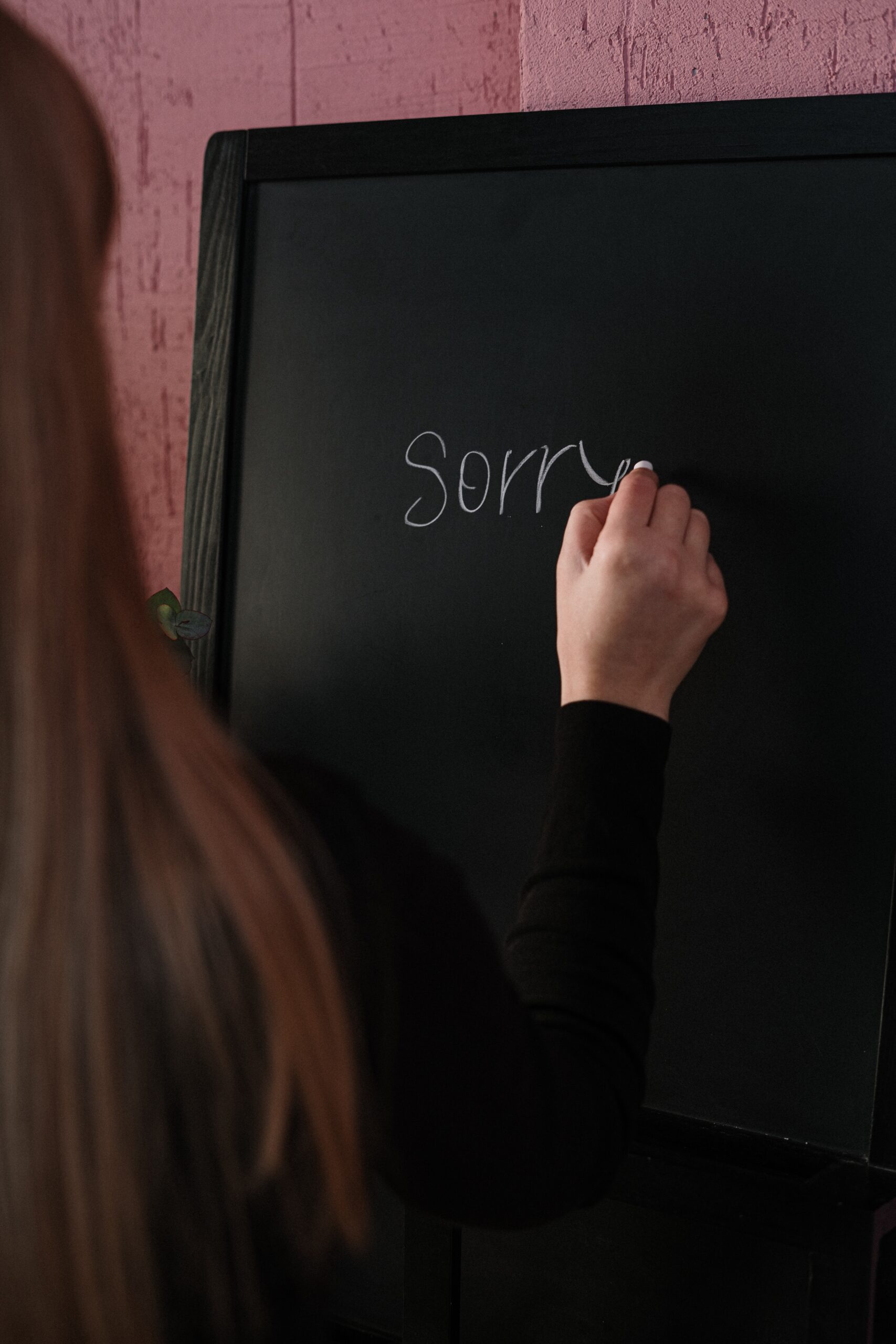

Later it came to mean “refined” or “elegant” with all those rough edges smoothed off (as in “polite society”). Eventually, it came to mean giving someone the benefit of the doubt, suspending your own needs so you can attend to the needs of others. That sense is embodied in the old joke: How do you make a Canadian apologize? Step on her foot.

More on Broadview:

- United Church’s 1st Indigenous moderator on why UCC’s apologies fell short

- Years of living in a small town nearly ‘white-washed’ me. Then BLM came along.

- Banning conversion therapy is step one. Here’s what needs to come next

But I think the meaning has morphed into something less nice and more backhanded. Politeness now seems to mean something closer to the original definition of a glossy, impenetrable surface. Being polite is a shield that protects us from facing up to issues that demand hard work and profound change. It’s politeness as deflection. We use it to shut down meaningful conversation.

It often comes off as sanctimony; perhaps even, outright passive aggression, the opposite of contrition. It’s more slap in the face than honest bid to examine.

And sometimes, it’s comedic code for calling out nastiness in others.

This is not to dismiss the delights of politeness as comedic code, which is a worthy artform. David Fisman, a University of Toronto epidemiologist, uses politeness to respond to the vilest of his anti-science Twitter critics. “Fanboy,” he calls one of the most scatological of them, with an affability born of outrage.

As a Lawrence Ferlinghetti fan, I unreservedly endorse the email I just received. So good. pic.twitter.com/TNLLWYKn2d

— David Fisman (@DFisman) June 26, 2021

In fact, a whole genre has arisen that is really a quasi-humorous front for that kind of verbal spanking – the “sorry, not sorry” phenomenon. Kathleen Wynne, then Ontario’s Premier, used it in a leaders’ debate during the last provincial election. “So here’s what I want to say about the last five years: ‘Sorry. Not sorry.’”

Comedy aside, I suggest another tack: embracing a national identity of tenderness rather than politeness. My dictionary tells me that “tender” comes from an ancient Indo-European verb meaning to stretch something thin. Think of tenderizing a flank of meat. It implies being soft. Metaphorically, that extends itself to the idea of being easily wounded, susceptible to grief. Being tender means opening yourself up to painful truths about how unjustly our society often works. It means playing your part to make things right.

None of this means that politeness has no place in Canadian society. Authentic politeness does, which is to say courtesy and grace. But not the sham stuff that gives us permission to walk away from the honest self-reflection we need.

***

EDITOR’S NOTE: This piece was updated on 13/07/2021 to refer specifically to unmarked graves in the first paragraph and to acknowledge that the author is not opposed to apologies played for comedic purposes.

Alanna Mitchell is a journalist, author and playwright with a deep wish to be cordial. At least sometimes.