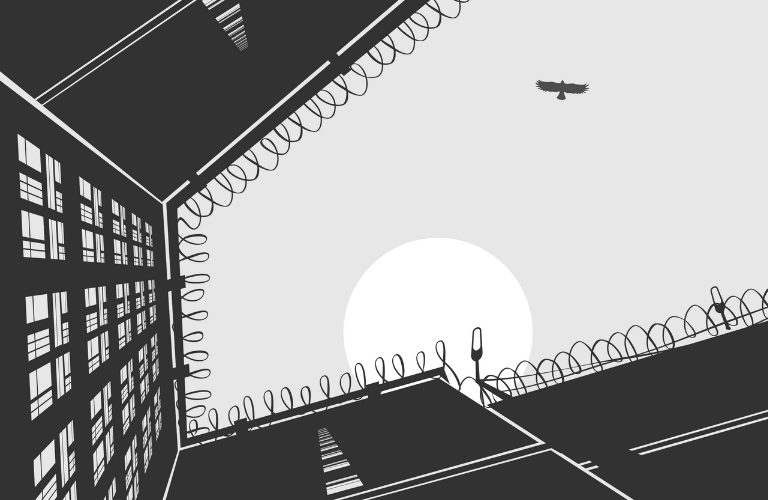

Canada has the death penalty again. No, offenders aren’t executed here anymore, but new rules governing parole eligibility mean that some might as well be. Since 2011, when the federal government made the changes, 15 people have been sent to prison, not to be rehabilitated or kept apart from society for a while — they’re there simply to die.

How did we get here? The death penalty was abolished in 1976, but the issue of sentencing persons convicted of multiple murders continued to bubble away. Canadian courts had long ago ruled that life sentences can only be served concurrently (running at the same time), not consecutively (one after the other). This led to a popular belief that all serial murderers would receive parole after 25 years of imprisonment. The tough-on-crime rhetoric called this “discount justice,” suggesting people ought to suffer more for committing two murders than they do for one.

The reality was that a person convicted of multiple murders was managed very differently by the correctional system than those convicted of a single offence. Before 2011, legislation already addressed the parole eligibility on multiple life sentences for separate convictions. For example, if a convicted murderer was found guilty of a second murder, the parole eligibility clock would start running all over again. And the parole board was never quick to release such people at first eligibility. But reality didn’t seem to matter, and uninformed perception ruled.

In 2011, the federal Conservative government found a constitutional back door that they felt allowed them to sentence serial murderers more harshly without contravening the court. Life sentences would still technically run concurrently, but parole eligibility could run consecutively. So, a person convicted of committing two first-degree murders could be ordered to serve two consecutive 25-year periods of parole ineligibility. In quick math, that’s 50 years in prison before eligibility.

To date, 24 cases have considered the new option and 15 made the order. Keep in mind some of these offenders’ parole eligibility dates: 2066, 2085, 2092. And then consider some of their approximate ages at that time: 81, 115, 132. Then remember the average life expectancy for men (and these are all men) is 78. The majority have no possibility of living until their parole eligibility date.

I am not the first or only person to call this our new death penalty. A wide body of international legal literature uses terms such as “a living death sentence” and “death by incarceration.” The Supreme Court of Canada said years ago that parole is essential to fair sentencing. Even the International Criminal Court, designed to hear cases of war crimes, enslavement, torture, mass rape and genocide, requires a review for parole-type release after 25 years of custody.

Usually one of the questions at sentencing is “what does the offender deserve, taking everything into account?” But I think with these extreme cases, that question loses its centrality. To me, the question should be “what do we as a society deserve?” Do we want to be the most vengeful? The most unforgiving? To erase all hope for some people?

In short, are we a nation that is prepared to take the lives of people who have broken the law? And if yes, can we still claim to be a society that believes in fairness, decency, humanity and redemption? If we demonstrate these values only to certain people, or only in the easy cases — is that the best we can be?

With several more of these cases to be determined in the near future, and with a federal election pending, now is the time to speak up. If you can’t do it for the offenders, do it for the kind of Canadian society you want to live in.

This story originally appeared in the March/April 2019 issue of The United Church Observer. For more of Broadview’s award-winning content, subscribe to the magazine today.

I, for one, do believe in fairness, decency and humanity. When it comes to redemption, I’m on the fence. I believe in second chances but when a criminal kills a second innocent person….and I say “innocent” as someone who is not involved in any criminal activity, my compassion goes to the family of those murdered. I want to live in a safe country where a two or more time murderer will not walk the streets again. If someone broke into my house and tried to harm my loved ones I will say straight up that it is my job to defend my family and if the intruder is killed in the process I have no qualms. However, if members of my family are killed and the criminal is sent away, I want to know that that person will not see freedom anymore. Each case is different. We each make our choices. Compassion and decency are good, but the balance, in my view, goes in favour of those who are brutalized, murdered, tortured and dehumanized.