The publication that you hold in your hands has persisted against all odds for almost 200 years. It has shaped church and country and consensus, while always courting controversy, which at first seems surprising for a little old religious magazine. It was born on a wing and a prayer (with a used printing press brought by stagecoach to York from New York City) and, improbably, served as the conscience of our nation.

In the late summer of 1829, some 30 Methodist ministers arrived from across Upper Canada to Bowman’s Chapel, a modest wooden structure in Ancaster Township (present-day Hamilton) for the first Canadian Conference of the Methodist Episcopal Church.

You may unsubscribe from any of our newsletters at any time.

Many who gathered were itinerant circuit preachers who spent their days on foot and horseback, their Bibles and sermons stuffed in saddlebags, spreading the word of God to settler communities on behalf of the Methodist Episcopal Church of the United States.

But the Canadian branch of the church had recently become independent, and its leaders had big plans to unite and educate their disparate flock of Upper Canadian Methodists, starting with launching a newspaper. At the meeting, founding ministers issued $2,000 in stock with shares costing $20 each. The Christian Guardian would publish weekly at York (later Toronto). The price per issue would be 12 shillings, and ministers who procured 15 subscribers were promised a free copy.

Those gathered also agreed to create a Methodist publishing house to print Sunday school papers and textbooks, establish the Upper Canada Academy to offer pre-university literary education to both sexes, and organize Canada’s first Total Abstinence Society to encourage teetotalling. Almost two centuries later, these early Methodist decisions echo throughout modern Canada. Upper Canada Academy stands as Victoria College, the oldest at the University of Toronto, with distinguished alumni such as Lester B. Pearson, Frederick Banting and Margaret Atwood. The Methodist Book Room became Ryerson Press and until 1970 published educational textbooks and literary work by many of Canada’s most important writers of the era. Abstinence, meanwhile, eventually fizzled.

But what of the weekly publication they envisioned?

The story of Canada’s oldest continuously published periodical, and the English-speaking world’s second-longest continuously published magazine is, remarkably, still being written today. Although it has gone through several transitions in its 195-year existence, this publication has served as a barometer of Canada’s evolving morality. It’s been confrontational, controversial, sometimes unapologetic, and at other times self-flagellating and insecure. It’s fuelled hope, sparked debate, probed ethical questions and been a progressive voice at the heart of many difficult conversations, most recently in defiance of a vocal Christian right.

With each incarnation, the publication has been led by pioneering editors who have made bold decisions, tested the line between church control and independence, and been editorially and economically inventive in the hunt for resources and readers. Among them: Egerton Ryerson (1829-32, 1833- 35 and 1838-40), Alfred C. Forrest (1955-77) and Jocelyn Bell (2018-present).

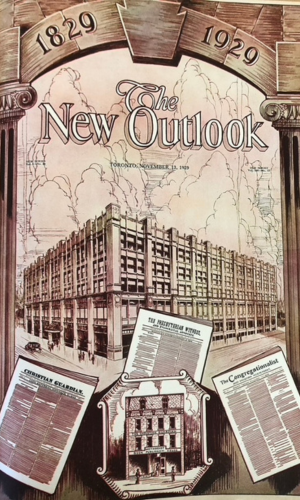

Reflecting on its history — from The Christian Guardian to The New Outlook, to The United Church Observer and now Broadview, a multiplatform media organization that includes a website, podcasting and online events — Bell says that words like “legacy and institution” start to get at what this storied publication means to her.

“The idea of standing on the shoulders of those who came before me is a helpful image,” she says. “Not just the past editors, but the thousands of voices of people who contributed to that ongoing conversation, as well as the people who read and engaged with it and allowed it to maybe shape how they saw Canada and the world.”

So much of Canada today would be unfathomable to The Christian Guardian’s first readers in 1829, but Bell says the publication serves as “one long thread that connects us to those people, one long conversation that both reflects and challenges the thinking of the day on what it means to be Christian and living on this land.”

More on Broadview:

-

Early pages of Broadview’s predecessor reveal a mixed legacy on Indigenous-settler relations

- How Broadview’s predecessor silenced Indigenous voices at Confederation

Over parts of three centuries, it has published bold stories and expansive commentaries that have unsettled congregations and even influenced church decisions: the future of Methodism, church land ownership, separation of church and state, public education, Indigenous rights, feminism, Darwinism and evolution, pacifism, the Palestine-Israel conflict, gay rights, abortion, residential schools, truth and reconciliation, right-wing extremism, atheism, trans issues and so many more.

It’s difficult to overestimate the influence the magazine has had over the years within — and beyond — the church. “For the sake of God’s world, it’s been pretty significant work,” says Mardi Tindal, former moderator of the United Church and current member of Broadview’s board of directors. “When I was moderator, I learned that you have to speak over the church walls, so more people get the message. This ‘broad view’ helps the church leave those walls and be heard more broadly in Canadian society.”

But with fewer people in the pews, religious publications are fighting extinction, an effort they share with many secular media. At Broadview, the precipitous decline in print subscriptions — and related revenue — over the past two decades sees it celebrating its 195th anniversary with a new strategy to ensure the only voice for progressive Christianity in Canada reaches its 200th and beyond.

It’s also worth asking a bigger question: in an age of resolute secularism, can this little old religious publication continue to make a difference?

***

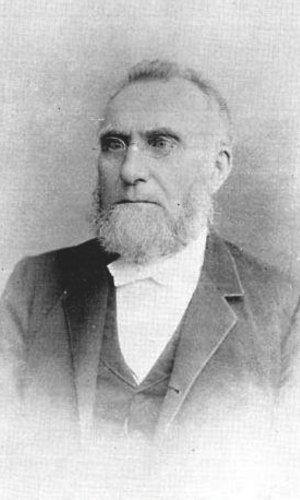

In 1829, pre-Confederation Canada was a wilderness society built on lands of the Wendat, Petun and Algonquin, populated by land-hungry farmers and United Empire Loyalists who had moved north around the time of the War of 1812 with America. Attendees to the Canadian Conference of the Methodist Episcopal Church, determined to reach these settlers through The Christian Guardian, elected as editor an intellectually nimble and verbose saddlebag preacher named Egerton Ryerson.

A descendant of United Empire Loyalists, Ryerson had defied his Anglican father to become a Methodist minister. As an apprentice preacher, he was assigned the Yonge Street circuit, which, riding on horseback over extremely shoddy roads, took him four weeks. While being a tenacious saddlebag preacher doesn’t seem like a qualification for founding editor, Ryerson, at only 26, “had become the public face of Methodist apologists in the colony,” according to York University professor Scott McLaren, an expert on the founding of The Christian Guardian. Condemned in the present day for his hand in creating the framework for the residential school system as superintendent of education for Canada West, Ryerson was, in his time, considered progressive, McLaren said in an interview.

Ryerson rose to prominence by publishing a series of letters in William Lyon Mackenzie’s Colonial Advocate, a weekly political newspaper, in which he dared to challenge two key ideas of the day: clerical monopoly over public education and the union of church and state. Ryerson’s first volley was an anonymous 12,000 words refuting attacks on Methodism made in a sermon by Rev. John Strachan. Strachan was a powerful clergyman and officeholder on the legislative council for Upper Canada (1820-1841). He was also a pillar of the Family Compact, which pulled the strings in the province. Its elite members were bound by position, pensions, sinecures, high-paying jobs and their connections to Britain.

During a sermon in 1825 on the death of Jacob Mountain, the first Anglican bishop of Quebec, Strachan had complained about the spread of Methodism across Upper Canada and its “uneducated itinerant preachers,” whom he witheringly described as being “induced without any preparation, to teach what they do not know, and which from pride, they disdain to learn.” Even worse, writes Kevin Flatt in an article in Faith Today, Strachan hinted that “the American origins of most of these preachers linked them with the rebellious attitudes of the new republic.” According to Flatt, an associate professor of history at Redeemer University College in Ancaster, Ont., “These were serious charges in a province where many settlers were Loyalists to the British crown who had fled the American Revolution and just fought off the Americans in the War of 1812.”

Strachan was deeply concerned about the influence of south-of-the-border Yankeeism that had driven out the British during the American Revolutionary War (1775-1783). The same insurrection could not be allowed to happen in the colony to the north, he averred, so the Church of England had to be bolstered as much as possible.

“If [Upper Canada] didn’t end up with an established church, it would mean that we would be all more susceptible to the wily influences of the Americans,” McLaren says. “The idea that there should be no connection between church and state was very controversial, because the British authorities believed that the Revolutionary War had happened because there were not sufficiently strong connections between church and state in the 13 colonies.”

Already, the men who drafted the constitution of Upper Canada in 1791 had set aside one-seventh of all property in the colony to support the Protestant clergy (specifically the Anglican clergy). They also gave Anglican ministers alone the right to solemnize marriages and provided funding only for Anglican missionaries and schools, thereby shutting out other denominations. This meant that any Protestants who wanted to be married, no matter their denomination, had to find an Anglican minister. Drawing on a long tradition of Christian thought linking church and state, Strachan believed that the Church of England was “the surest means for the promotion of sound Christian principles, an orderly society and loyalty to the Crown,” Flatt writes, and would guide the province’s settlers away from the influence of Roman Catholicism and “a welter of disorderly Protestant sects.”

In his writings, Ryerson denounced Strachan and the Family Compact and argued for a degree of separation between church and state; specifically, he didn’t believe the Anglicans should be the colony’s official church, despite the denomination’s primacy in Mother England. At the very least, he argued, the government of Upper Canada should treat all Protestant denominations equally. Ryerson felt Methodists should be allowed to solemnize marriages and collectively own property to build churches, and that the lands set aside for clergy, known as “clergy reserves,” should be sold and the proceeds put into a free, non-partisan, public education system. On a personal level, Ryerson also rejected Strachan’s claim that Methodists were disloyal to the British, evoking his own family’s Loyalist origins and service in the War of 1812.

Throughout all the back and forth, it became obvious the Methodists in Upper Canada needed to defend their interests, as well as to separate themselves from American Methodists. “Egerton Ryerson felt that in order to really advocate for the kind of political and educational change he wanted to see, they needed their own publication,” McLaren says.

The ever-ambitious Ryerson put his name forward as editor and got the job. He set off for New York City to acquire a $700 printing press and paper. “I’m astonished that The Christian Guardian got started at all,” Jim Taylor, a former managing editor of The United Church Observer, mused in a 1979 article celebrating the publication’s 150th anniversary. “It took him six days to get there, by stagecoach, over what were later described as ‘the worst conceivable roads,’ at a rate of a mile an hour.” Back home, Ryerson’s budget was too small to hire staff, so he folded and addressed the papers himself to send to subscribers — 450 a week at first. Soon, though, there were 3,000 subscribers, the largest circulation of any periodical in the country at that time.

The Christian Guardian was supposed to be modelled on the New York-based Methodist publication, the Christian Advocate, but it “was actually quite different from almost the very beginning because it appealed not just to Methodists, but to everyone,” says McLaren. “There was definitely lots of religious content in The Christian Guardian, but there were also really strident articles arguing for the secularization of the clergy reserves.”

Ryerson wrote in 1830 that The Christian Guardian’s role was “to support and vindicate religious and civil rights,” but also to promote “practical Christianity — to teach men how to live and how to die.” He had a “democratic impulse,” McLaren says, and believed in “waging a newspaper war to change people’s minds because he thought their opinions mattered.” Ryerson’s editorial skill and a growing constituency of Methodists made The Guardian one of the most politically influential papers in the colony. One detractor, according to McLaren, sneered that The Christian Guardian “went into every hole and corner of the Upper Province.”

Ryerson’s opinions didn’t only irritate Anglicans. Politically conservative British Wesleyans also said that The Christian Guardian was “way too political,” in McLaren’s summation, and that Ryerson should get off his “political soapbox, stick to his knitting, and focus on saving souls and not worry about how the province is organized politically.”

Notorious for being unpredictable in his opinions, Ryerson ended up supporting a Methodist merger with the British Wesleyans who were expanding their work into Upper Canada. He resigned as editor in 1832 to go to England to complete the negotiations. He returned to Upper Canada in September 1833 and resumed editorship, only to resign again in 1835, seemingly worn down from all the controversies he’d ignited or become embroiled in.

An account of his life published after his death, edited by his friend J. George Hodgins, says that Ryerson “longed for more congenial work” and passionately wanted to focus on a universal, free education system.

In his 1835 farewell to readers, he recalled how far his church had come since he launched The Christian Guardian: “Methodists were an obscure, a despised, an ill-treated people; nor had their church the security of law for a single chapel, parsonage, or acre of land.…Now the political condition and relations of the Methodist connexion are pleasingly changed. Ten years go there were 41 ministers and 6,875 church members; now there are 93 ministers and 15,106 church members. We may well thank God, therefore, and take courage.”

Under Ryerson, “the newspaper earned its reputation as an unyielding thorn in the side of Upper Canada’s conservative governing elite as it opened a new space where policies could be debated, elections influenced, and political figures scrutinized,” McLaren writes in “Before The Christian Guardian: American Methodist Periodicals in the Upper Canadian Backwoods, 1818-1829,” published in the Papers of the Bibliographical Society of Canada.

While McLaren stops short of concluding The Christian Guardian prevented the Church of England from becoming Upper Canada’s official religion, he does believe that “so central did The Guardian become in the reformist battle for religious neutrality on the part of the state, that its impact on the colony’s political and cultural life can be overstated only with difficulty.”

McLaren also sees a thread running from The Christian Guardian to today’s Broadview: “It was advocating…not just for religious change, but political change, with an eye towards bigger issues around things like equity and fairness and political representation. As well as also bringing marginalized voices, and even to some extent Indigenous voices, into a conversation that was happening in Upper Canada.” Early Canadian Methodists “felt you couldn’t deal with just religious issues unless you also dealt with political issues. You could say that’s true of most people in the United Church today,” McLaren says.

Persuaded by supporters, Ryerson ran one more time to be editor and was re-elected, serving from 1838 to 1840 before finally retiring again. Over his 11 years at the helm, he set the standard for subsequent editors of the publication: crusading, curious, contrarian and, by necessity, resourceful.

***

No matter the edition, the century or the reigning editor, a reader of this publication is exposed to stories of consequence to the evolution of Canada intermixed with reports of church decisions, religious instruction and theological perspectives. A reader in 1837 would find in-depth coverage of that year’s Upper Canada Rebellion, or between the two world wars, a strong defence of pacifism.

Rev. William Black Creighton, who became editor-in-chief in 1906, was a passionate pacifist who influenced the beliefs of tens of thousands of readers, contradicting the position of the Canadian government. “The open promotion of pacifism in the pages of The Christian Guardian in early 1924 led to relief for pacifists but alarm for those who sought to defend the just war tradition,” according to Gordon Heath, professor of Christian history at McMaster University in Hamilton, writing in 2019 about the peace movement within the United Church. In 1924 alone, Heath cites Guardian articles and editorials that questioned militarism and the risk of nationalism, with headlines like “How Can War Be Outlawed?” (March 5); “Stirring Debate on No More War” (April 16); “Nationalism as a Menace” (May 7); and “The Struggle for Peace: A History with Its Pathos and Tragedy” (May 28).

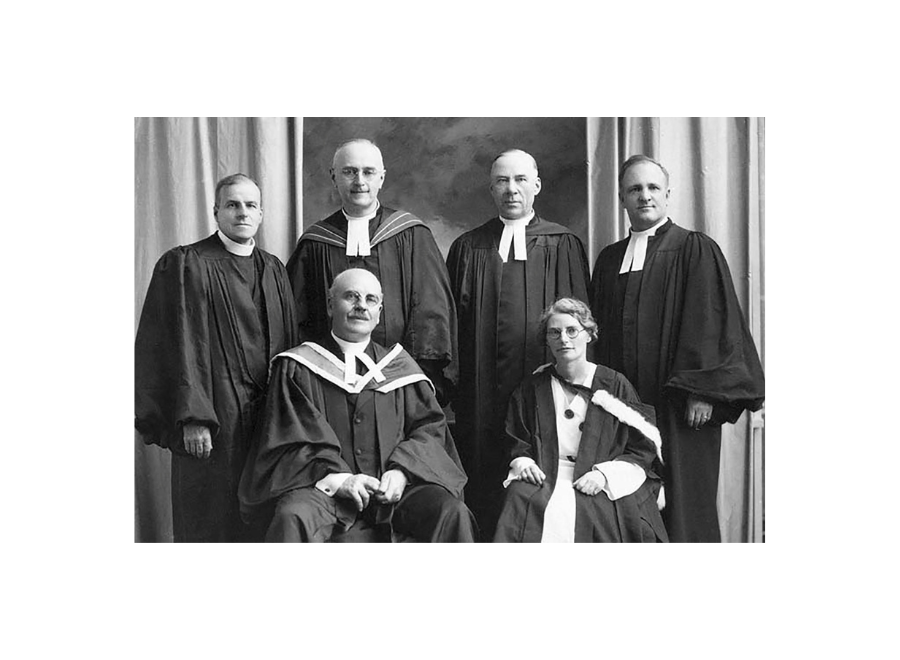

Creighton edited The Christian Guardian until 1925, when The United Church of Canada was formed through the union of Methodists, Congregationalists and most Presbyterians. Their respective publications merged to form The New Outlook, and Creighton remained editor until 1937. Then in 1939, the church’s General Council amalgamated The New Outlook with The United Church Records and Missionary Review, and The United Church Observer was born. This was the first and only time that the publication’s name would be directly tied to the church it served, affirming it a powerful two-way mirror for a growing denomination: it reflected the views of church members as much as it influenced them.

Under editor Rev. Alexander James Wilson (1939-1955), The Observer combined both the weekly newspaper and monthly magazine formats into a bimonthly magazine. The circulation skyrocketed, from 11,500 in 1939 to 150,000 by 1955, driven by the amalgamation of publications as well as the popular Every Family Plan that saw congregations pay for the subscriptions and give them to “every family” (or every family who agreed) in their congregation for free.

It was during this time of exponential circulation growth that Rev. Alfred C. Forrest took the helm and audaciously and passionately steered The Observer into controversy.

A graduate of the University of Toronto’s Victoria College, one-time sports reporter for the Globe and Mail, minister at three churches and chaplain in the Royal Canadian Air Force, he was urbane, inquisitive, iconoclastic and well travelled. He’d become known as an in-the-trenches editor, who’d once covered 22 African countries in 10 weeks. “Forrest, like Ryerson, was not afraid to challenge prevailing opinion,” according to Ruth Bradley-St. Cyr, an Ottawa-based researcher and former managing editor of the United Church Publishing House. She did her PhD on the “downfall” of the Ryerson Press, which included research into Forrest, whose years as Observer editor overlapped with the final decade of the press.

Forrest enjoyed courting controversy as a notorious Christian commentator, noting that his friends and fellow opinion leaders Pierre Berton, Charles Templeton and Gordon Sinclair were all atheists. “While atheism certainly does not disqualify a man from making profound and helpful comments on religion,” he wrote, “it would be helpful if the media produced more men of equal competence in communication but greater profundity of understanding.”

In an interview in 1963 with the Toronto Daily Star, he joked that he had been called “everything but a Christian” and said those who wanted the church to keep quiet failed to understand that it was the the church paper’s responsibility to cover “anything that comes between a man and his God.”

According to Bradley-St. Cyr, Forrest had the gift of considering both sides of an argument and a willingness to change his mind. In the 1960s, he criticized Canadian immigration policies because they “favoured Roman Catholics,” but when he was an observer that decade at Vatican II, he reported that Pope John XXIII (now Saint John XXIII) was “the best pope Protestants ever had.” Bradley-St. Cyr says Forrest was also opposed to the secularism sweeping Canada in the late 1960s, calling it “the faith of Expo ’67” or “the belief that man can make it on his own, achieve and bring about a wholeness within his life without spiritual help.”

Jim Taylor, Forrest’s managing editor, says Forrest had a great appreciation for global issues but also felt deep ties to the magazine’s readers. “He saw the Canadian church as his pastorate.” And like any pastor in a local church, he felt “the national church has no business telling a local pastor what he should be preaching. And I think he applied that through The Observer.” Forrest also sent Observer representatives across Canada to meet his congregation of readers. For many, it was the first time someone from the United Church national office had ever visited a local presbytery, says Taylor.

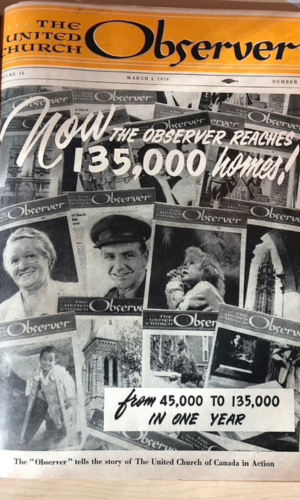

Under Forrest — and thanks to a growing United Church membership and the Every Family Plan — circulation doubled to 334,000, making The Observer the biggest denominational publication in the Commonwealth. By then, more than 2,800 United churches were enrolled in the Every Family Plan to purchase subscriptions for their parishioners.

Just as Ryerson shaped readers’ views on clergy reserves and the separation of church and state in the 1830s, and Creighton spread pacifism in the 1920s, Forrest’s criticism of the state of Israel for its actions against Palestinian refugees put him at odds with much of the Canadian establishment.

However, his ongoing reporting swayed many in the United Church to the Palestinian cause. Over his tenure, Forrest offended Unitarians, Catholics, Jews, big business, organized labour and even the Toronto Campaign for Nuclear Disarmament. He explained to the Toronto Daily Star that “people confuse our editorials with the official position of the United Church. The editorials are my responsibility and mine alone.”

Despite the controversy, the church tended to support the freedom of its own press and its editor, Bradley-St. Cyr says. Forrest’s courting of controversy brought death threats and harassment. His hard-headed determination in running a magazine that tweaked people’s consciences elevated his Observer to must-read status but also took a profound personal toll. Forrest’s controversial stands wore him down, says Taylor, who recalls his mentor with deep fondness, describing him as a “second father.” “Al is linked with two main issues — support of Palestinians and that he was opposed to abortion,” says Taylor. In 1971, when the United Church declared that abortion was between a woman and her doctor, Forrest opposed the church policy and lobbied to get it changed, he says.

In summer 1977, Forrest ran for moderator of the United Church and lost. “He felt it was not just a rejection of his value, but a rejection of The Observer as a whole, as a ministry of The United Church of Canada,” Taylor is quoted as saying in an appendix to Bradley-St. Cyr’s doctoral thesis. Eighteen months later, Forrest died. He had been complaining of insomnia, according to Taylor, and his doctor told him to read when he couldn’t sleep. On the morning of Dec. 27, 1978, he woke around 4 o’clock and went to the living room to read. He was found in his favourite chair with a book still in his hands, dead of a heart attack. He was 62.

***

Welcoming gay ministers. Apologizing to Indigenous survivors of residential schools. Advocating for climate justice and ecological healing. Between Forrest’s tenure and today, editors have reported on the church’s decisions and drawn on their own passions and approaches to lead the magazine, always responding to, and influencing, readers by asking hard questions about who and what Canada should be.

Hugh McCullum, beginning in 1980, was the first layperson appointed editor/publisher. He wasn’t even a member of the United Church. He had been a reporter at the Toronto Telegram for many years and then editor of the Anglican publication Canadian Churchman. He made his mark visiting Biafra in 1969 amid its civil war with Nigeria and wrote movingly about his experiences for the Churchman and The Observer. Under McCullum, The Observer evolved from an arm of General Council to an independently incorporated publication that could set its own editorial direction. This shift also made the magazine eligible for a postal subsidy when mailed to subscribers. Like Forrest, McCullum travelled extensively, reporting on struggles for justice in Northern Canada, Central America, Africa, the Middle East and Asia.

David Wilson (a future editor/publisher) was working at a movie tabloid in 1987 when he was hired by McCullum, who he describes as “a very flamboyant editor” who liked big-picture stories and taking risks. “He wanted the magazine to matter and to reach beyond the church constituency,” says Wilson. Taylor, however, compares McCullum’s approach to turning The Observer into Newsweek. “Hard news, but focusing on social justice issues,” he recalls. “He had very little sense of congregation life and wasn’t interested in most church news, which is often soft news.”

Within a year of joining the magazine, Wilson had a dream job that any journalist would envy. McCullum sent him across the United States for five weeks to interview the Christian right in the run-up to the 1988 presidential election that ushered George H.W. Bush into office. Wilson received a National Magazine Award nomination for this first major piece. That year, he also travelled to Alberta to cover a regional conference where the issue of ordaining self-declared gay men and lesbians as ministers was top of the agenda. The General Council’s decision later that year to approve the policy caused The Observer to lose tens of thousands of subscribers, Wilson estimates, “because the magazine was the messenger to people who were angry with the church.” (The United Church lost almost 80,000 members between 1987 and 1991.)

After McCullum (1980-90) left to work in Africa in various communications and ecumenical roles, writer and editor Muriel Duncan (1990-2006) took over. In addition to having a deep appreciation for congregational life, she had written numerous stories about the campaign to welcome openly gay and lesbian ministers into the church and the ensuing split within the denomination. She wrote the definitive article about the gay ordination decision at the 1988 General Council in Victoria. She was also one of the first journalists in Canada to expose the physical, sexual, spiritual and cultural abuse that Indigenous students suffered in residential schools, including those run by The United Church of Canada.

Mardi Tindal was the co-host of a United Church television program, Spirit Connection, when the church was grappling with issues of sexuality and later, deciding whether to apologize for its role in residential schools. Thanks to reporting in The Observer, Tindal learned that the 1998 decision to apologize for The United Church of Canada’s role in residential schools was made against the advice of the church’s insurers and the insurers’ lawyers. She says she appreciated that The Observer reported on church decisions with a critical eye.

Wilson took over from Duncan in 2006. Magazine circulation had gone from more than 300,000 in 1975 to about 60,000, alongside vast declines in church attendance. A discounted group subscription plan, handled by volunteer representatives in each congregation, had begun to replace the Every Family Plan in the mid-1980s.

Wilson says his vision was “to create a church magazine that exceeds expectations of what a church magazine might be.” He switched to glossy stock from newsprint, emphasized the design of the magazine and paid freelancers what they earned from mainstream magazines like Toronto Life, Maclean’s or The Walrus. He also expanded the scope of the magazine to more deeply examine ethical living and social justice issues that didn’t have an overt religious component.

“The magazine was a voice for enlightened Christianity in a Canadian context. It made a case for those values to be part of the Canadian conversation,” says Wilson, who notes The Observer led with its stories on women’s rights, immigration and refugee policies, war and pacifism, among many others. He likes to think the coverage had an effect on national policy.

Still, Wilson says he knew he was “presiding over an embattled medium in a shrinking universe.” Between 2011 and 2021, United Church membership dropped from about 480,000 to roughly 350,000 people, and church attendance declined from more than 165,000 to fewer than 120,000 people. This meant the audience for The Observer was shrinking too.

By the time Jocelyn Bell, a longtime writer and editor at the magazine, was named editor/publisher in 2018, the magazine’s circulation had dropped to about 31,000. She sought to understand what The United Church Observer should and could be in a world where churches were losing their faithful and magazines across North America, including religious publications, were shuttering. At the same time, she wanted to foster important conversations about how we can live ethically and in balance within our modern world. With the assistance of her own team and publishing consultant Sharon McAuley, who had been publisher of Toronto Life and Saturday Night magazines, she re-envisioned and rebranded the publication.

A year later, in April 2019, Broadview was launched: a multiplatform media organization that eventually grew to include a reinvigorated website and archive, podcasting and online dialogues with readers, including a national reading club. Its new tag line was “Spirituality, Justice and Ethical Living.” Bell says the strategy was needed.

“According to our own projections, we would have been closing shop in 2024. But I think it’s more than that. If we hadn’t made the transition, we would have missed the opportunity to share journalism through a progressive Christian perspective with people beyond the United Church pews. The Observer was producing some really great journalism, but very few people outside the denomination ever read it,” says Bell.

She adds that Broadview wants to reach people both within the church and beyond it. Among them are people who consider themselves progressive Christians as well as those who don’t identify that way but share the values of progressive Christianity. “I think a lot of creative energy has come from thinking about what values those groups have in common and how we can best serve their needs,” she says.

D.B. Scott, a recent Broadview board member and author of the Canadian Magazines blog, thinks building a broader audience is vital, while also continuing to report on the church. He says it’s been a major preoccupation of the board.

“Holding on to an audience in the modern circumstance is no easy matter when you’re trying to get somebody to part with a little bit of money. And goddammit…it’s not like you’re asking for the Earth, the moon and the stars,” says Scott.

To retain or grow an audience, the publication must “have the right story to tell them,” he says. “I have always felt that the readers of magazines are subscribed to the principles and the end, the focus of the publication, not so much to the individual articles.” That said, the progressive content that the magazine is introducing to an older existing audience still has to resonate with them.

All magazines are struggling, and it’s also expensive to find, reach and secure new readers while holding on to current ones, he says, adding that Broadview’s website and newsletters are an important strategy to bolster the audience.

After the April 2019 rebrand, the loss of subscribers slowed, but then COVID-19 hit and “it was not kind to us,” says Bell. Generous donors have stepped up to fill in some of the budget shortfall.

And Broadview is evolving to think of itself as a charity whose mission is to provide progressive Christian journalism aimed at changing the world. In 2022, Bell hired Rev. Trisha Elliott, an ordained United Church minister, longtime freelancer for the magazine and certified fundraising executive to oversee efforts to raise money. This year, she promoted Elliott to executive director and is expecting fundraising to bring in almost half the organization’s revenue, with subscriptions, grants, advertising and investment income making up the rest.

While the editors who came before Bell had the luxury of stomping through the trenches to bring important stories to church members, today she turns her focus to running a multi-platform media organization with razor-sharp budgeting. “We’re a magazine, a website, podcasts, videos, e-newsletters, virtual events. We’re uploading to Apple News and YouTube and at least four other social media platforms,” she says, explaining the many efforts underway to grow the audience. It’s a lot of adapting and evolving, she says. Across all those platforms, monthly reach is about 137,000.

That said, the issues Bell cares about and champions populate Broadview, sparking important discussions on 2SLGBTQ+ rights, women’s rights, racial equality, climate justice and reconciliation with Indigenous Peoples.

She wrote in December 2023, if “my imagined future historians find this issue of Broadview, they’ll gain insights into how we viewed the climate crisis and multiculturalism and how we dabbled with artificial intelligence to produce a tongue-in-cheek interview with AI Jesus. They’ll also learn about how Indigenous United Church members are carving their own path to self-determination, just as the Algonquian teachers engraved their presence and world view into the marble. Most of all, I’d like the 3023 crew to read our piece on Mary, the mother of Jesus.…Our story in this issue reinterprets Mary as not just a portal but a prophet in her own right.”

She closed that piece with an ode to stories that have the “power to speak to us for millennia,” writing: “I believe that those that last the longest are the ones that stir our emotions, give us new knowledge, make us feel connected and inspire us to build a kinder, gentler world.”

Broadview is “now standing with the best magazines as much as possible,” Bell says, and has won numerous National Magazine Awards (NMAs), Canada’s highest accolade for magazine journalism. In 2020, Bell also won the NMA’s Editor’s Grand Prix, for “the complete re-visioning of Broadview magazine,” according to the NMA jury, and was later a runner-up, along with Sharon McAuley, for publisher. The NMA also awarded Broadview the Best Magazine: Special Interest in 2021 and 2022.

As Broadview experiences pressure to find new readers, it also finds its relations with the national office of The United Church of Canada under strain. The national office, itself having gone through a 2019 restructuring and fallout from the pandemic, cut its grant to Broadview in half and drastically reduced advertising in the magazine and online. Now, that grant is $40,880, which represents two percent of Broadview’s budgeted revenue this year. Broadview journalists have also been barred from General Council Executive meetings that they had attended in the past.

And changing the publication after 80 years remains controversial to some observers and longtime readers. Phyllis Airhart, a professor emerita of the history of Christianity at the University of Toronto’s Emmanuel College, says she wondered if the changes made Broadview less valuable to the church.

“I’ve wondered whether the new format, with the United Church as a separate ‘focus,’ combined with their own budget pressures will give them cause to reconsider its value,” says Airhart, author of A Church with the Soul of a Nation: Making and Remaking the United Church of Canada. “I assume the editorial decision was made in an attempt to expand the readership beyond the denomination. But does it give the impression that the United Church is less important to its future?”

Many people interviewed for this piece are watching closely to see what Bell and Broadview do next, worried about the future of Canada’s oldest continuously published magazine.

Tindal believes the magazine retains its critical role in informing the conscience of our often-fragmented country as fewer Canadians identify with an institutional faith.

“The task of building community has become infinitely more complex, and importantly, more vital,” says Tindal. “In a world where media often focus on what divides us, Broadview provides common ground where we can develop a deeper understanding of differences and what unites us as human beings.”

As the 195th anniversary approaches this fall, Bell and her team are focusing on inspiring readers through solutions-based journalism, embracing a charity model, harnessing technology to develop readership, and putting strategies in place for financial stability and growth. Bell says that “hope and a lot of hard work” will help Broadview chart a path forward, clarifying its vision and purpose for 2025 and beyond.

The Christian Guardian began on a wing and a prayer and a used printing press — and still managed to make its mark. Can Canada’s oldest continuously published periodical continue to make a difference?

Maybe it’s best to conclude that this very old and very storied publication, led by crusading, passionate and committed editors, lives on hope — hope that what began with such grit and faith in 1829 continues to evolve and thrive and guide critical conversations about Canadians.

“One thing I’ve learned in my time as editor/publisher is that our readers and supporters are willing to take risks with us; they’re willing to evolve,” says Bell. “We all cherish and celebrate the past. But we also all know we can’t cling to it, and there are critical points at which you have to let it go and keep moving. This publication has been reinventing itself for 195 years. We intend for that adventure to continue.”

***

Shelley Page is a long-form feature writer, editor and content strategist in Ottawa who has won multiple awards.

This story first appeared in Broadview’s October/November 2024 issue with the title “195 Years.”