I entered quarantine with a broken heart.

It was one of those relationships that comes into your life with the velocity of a hurricane and disappears just as quickly, leaving you winded and hollow for months.

I took the month of February to lick my wounds, expecting to get back on my feet by the time I finished my undergraduate degree in March and started a CBC internship in April. After that, I would fulfill my dream of moving to Toronto to pursue a career in journalism, starting with an internship at this publication.

I had it all worked out – a stable recovery, a perfect end to my schooling and a promising start to the rest of my life. Then the apocalypse hit.

Classes were moved online, my convocation was indefinitely postponed, my CBC internship was cancelled, and I was stuck in my Ottawa apartment — heartbroken, separated from my friends, and forced to watch as my carefully plotted future melted away.

I slipped into a pseudo-catatonic state for the first few weeks of quarantine. Years of therapy unravelled before me, and I reverted to a self-destructive version of myself that I thought had receded a long time ago.

After several weeks of outright numbness, I started whittling away at little chores to restore some sense of normalcy. The most rewarding one was packing up my room – a fleeting attempt at pretending my move to Toronto was going to happen anytime soon. In my excavations, I found an old treasure from my philosophy degree tucked away on one of my bookshelves – The Consolation of Philosophy, the magnum opus of sixth-century Italian thinker Boethius.

A politically active philosopher, Boethius was accused by his rivals (under dubious pretenses) of conspiring to overthrow Theodoric, the king of Italy. He was subsequently sentenced to death, and spent two years under house arrest staring down an inevitable execution for crimes he didn’t commit. He was separated from his family, unable to interact with the outside world, and left alone in his home with only a crippling sense of dread to keep him company.

More on Broadview: Noam Chomsky on the private interests undermining democracy

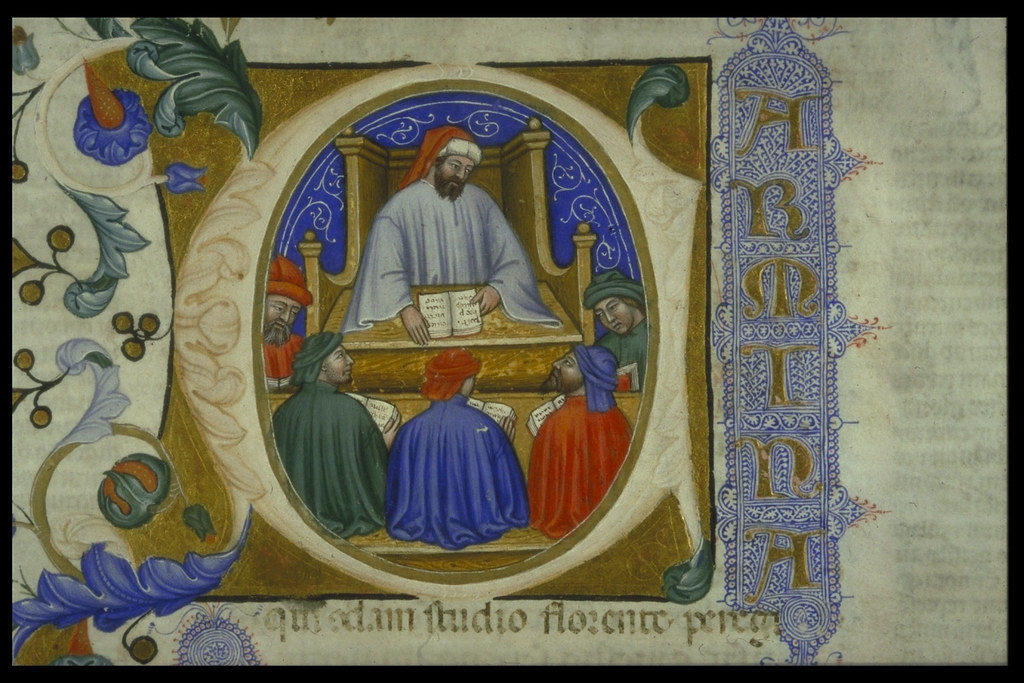

Consolation is an epic dialogue between a semi-fictional version of Boethius and Lady Philosophy, the latter a vivid personification of the author’s cumulative studies in classical thought. The book combines gorgeous poetry with cosmic philosophy as Lady Philosophy reasons Boethius out of his sorrow by showing him the pointlessness of his despair.

When I first read Consolation in 2017, a fate like Boethius’ seemed unimaginably painful and difficult. Now, the whole world is Boethius, but no intellectual apparition is teleporting into our quarantines to save us.

I stuffed the rest of my books into nondescript cardboard boxes, but I left Consolation to the side. I hoped that I, too, could partake in Boethius’s glorious consolation. Could Lady Philosophy also stitch together my heart and mind?

There was only one way to find out. I settled in my room, poured myself a cup of chai, flicked on the new Fiona Apple album, and readied my mind for philosophical rejuvenation.

Lady Philosophy begins her work slowly. Coming upon a distraught, frenzied Boethius, she applies a balm to his wounded soul. She gently reminds him that the source of his sorrow is the loss of his possessions – his family, his career, his reputation, his life. But the thing is, says Lady Philosophy, Boethius never owned any of that. It’s pure hubris to think that anything – even one’s own family – belongs to them. It belongs to Fortune and Fortune alone, explains Lady Philosophy. And Fortune gives just as much as she takes.

That was Boethius’s first mistake. His second, and much greater, mistake was thinking that impermanent things could bring him happiness. He thought things like fame, joy, riches and status would make him happy, but they never could, because those things were all given to Boethius by others. Happiness can only come from within, says Lady Philosophy, and a life spent pursuing external pleasure and validation will only ever result in misery.

Boethius now finds himself rid of his previous anguish, but unsure of how to secure true happiness. But Lady Philosophy, as always, has got his back. “I shall show you the way which will bring you back home,” she promises. “I shall also equip your mind with wings to enable it to soar upward. In this way you can shrug off your anxiety, and under my guidance, along my path, and in my conveyance you can return safely to your native land.”

I hoped that I, too, could partake in Boethius’s glorious consolation. Could Lady Philosophy also stitch together my heart and mind?

This promise of Lady Philosophy’s gave me pause. Acquiring wings which would let me “shrug off” my anxiety seemed lovely, but was a 1,500-year-old book really going to do that for me? Armed with healthy skepticism, I forged onward.

There is no such thing as evil people, Lady Philosophy explains. Only good people who use their free will to pursue false goods, like fame or wealth. Nobody wronged Boethius; they were just pursuing bad things thinking they were in the right, and Boethius got caught in the crossfire.

Following in the footsteps of Aristotle before her, Lady Philosophy explains that happiness is only possible if you are good in everything you do. If you trust that you are enough, and that the only thing that can make you whole is yourself, then you will be happy. “Once earth is overcome,” she explains, “the stars are yours for the taking.”

I closed the book, my mug empty, Fiona Apple’s voice long gone from my speakers. I glanced up, half-expecting to see a towering Lady Philosophy hanging over me. I checked in with myself; my mind was still scattered, my heart was still broken, and my body was still in quarantine. But a familiar warmth spread through me – little inklings of serenity nudging out what was once anxiety.

Lady Philosophy isn’t going to appear in my home and rescue me from myself. But she didn’t rescue Boethius either. She was just the personification of his own journey in remembering what’s important by way of the wisdom of those who came before him. I turned to Boethius, just as Boethius turned to Plato and Aristotle.

It was silly to think The Consolation of Philosophy – or any other external thing – could ever really console me. But it took the exercise of picking up the book to realize that only I am capable of conquering my circumstances. And now, I’m ready to take the stars.

Broadview is an award-winning progressive Christian magazine, featuring stories about spirituality, justice and ethical living. For more of our content, subscribe to the magazine today.