He came 35 years before slavery ended. It would be more than a century and a half before segregation was over. But when Methodist minister John Stephenson arrived in Bermuda, he came preaching equality.

More than 200 years later, in the town of St. George’s, David Atwood got up in front of a crowd of 80 with Stephenson on his mind. The current chair of the Wesleyan Methodist Church synod was there to apologize: to the minister’s ghost, and to everyone since who’s suffered the sting of prejudice in the synod’s churches.

You may unsubscribe from any of our newsletters at any time.

“The Synod of the Wesleyan Methodist Church of Bermuda did not continue Rev. Stephenson’s ministry to all. We did not follow his example in the way he followed Christ’s example,” Atwood said in his speech last November. “We allowed the sin of racism to enter our churches in the form of segregation, and for this we are deeply sorry.”

It’s a moment that’s been compared to the United Church’s apology for its role in Canada’s residential school system. The comparison is more than an idle one — the Wesleyan Methodist Church has been a part of The United Church of Canada since 1930 and remains a member of the church’s Maritime Conference. As in Canada, too, the Bermudian synod was apologizing for wrongs of the past: in this case, years of segregation and the systemic racism that emerged in its churches as a result. The after-effects of that time still resonate in Bermudian society today, while other prejudices continue to create divides on the island. With the apology as a start, the synod hopes to bridge these divisions within its congregations, creating an ongoing example for equality.

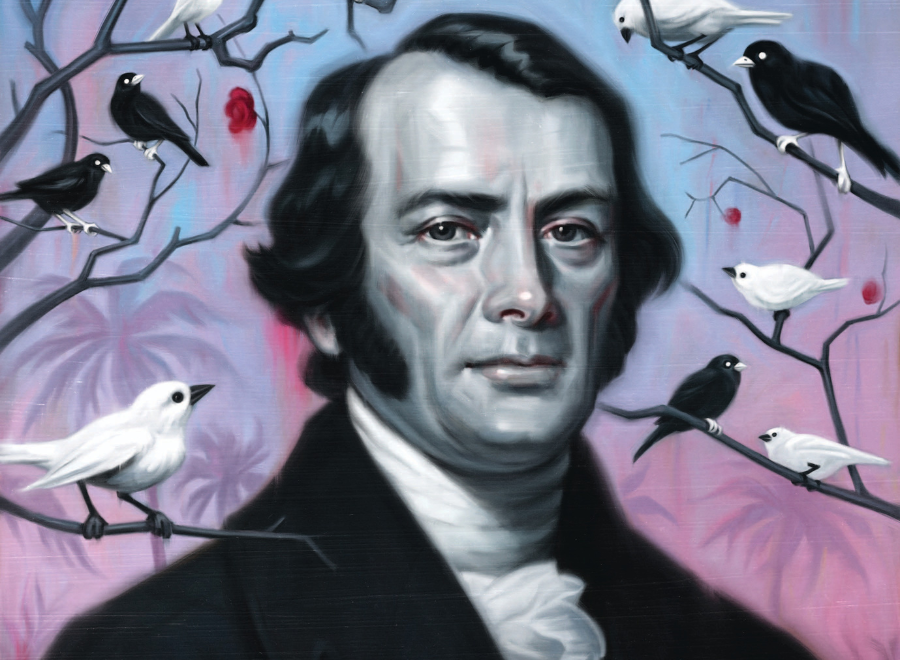

Stephenson set the standard for that equality centuries ago. “He came at a time when slavery still existed in Bermuda, and he had black and white Bermudians worshipping together,” Atwood explains in an interview months after his speech. Arriving in 1799, a time ripe with racial tension, the Irish-born Stephenson was arrested and jailed for six months in response to his race-blind ministry. That didn’t stop him: he continued to preach through the bars of his cell. Once set free, though, Stephenson didn’t last long in Bermuda, leaving in 1802, just three years after he first arrived. Today, a plaque — along with the original cell grating from the prison he was held in — is on display at St. George’s Historical Society Museum, memorializing the rebel Methodist.

Over the years, though, the church — which today is fairly evenly split between black and white members — got waylaid from Stephenson’s path. “We’re really not quite sure what happened and when it happened, but we started to be influenced by the segregation that was occurring in the community, and we lost that first inclusion that he established,” Atwood says. “There are people in Bermuda today who have experienced prejudice and exclusion within their own lifetimes.”

Segregation lasted officially in Bermuda until 1959, though it lingered in churches into the 1960s, leaving a lasting mark on the people who lived through it. Take, for example, Leo Mills, an active member in the Wesleyan Methodist Church. He still remembers accompanying a vacationing American family to church after meeting a new friend at a parade in Bermuda’s capital, Hamilton, 60 years ago; Mills — then six or seven — skipped to a front pew to sit alongside the white family. He was too young to know that by doing so he was making a statement. “I could feel thousands of eyes on my neck,” he says. “It was such a huge metaphor for how the gates suddenly sprang open and crumbled on that one occasion.”

For Mills, the incident is a distant memory, and he smiles at his unintended insolence now. For other black members of the congregation, however, those memories are still painful. Adele Halliday, team leader for Transformational Ministries with The United Church of Canada, visited Bermuda in November 2007, writing a report based on her findings. There, she called racism “the single most urgent issue facing congregations in the Synod of Wesleyan Churches in Bermuda today.” Many black members she spoke to still sat in the same pews they were forced to occupy during segregation, and “didn’t feel welcomed in positions of leadership”; some even left to join the African Methodist Episcopal Church. Despite the concerns congregants shared with Halliday, though, racial tensions weren’t acknowledged openly between members. “Some people certainly felt like, ‘We can talk about racial justice issues in society,’ but that it was no longer an issue in church because we’re all God’s children,” Halliday remembers.

Racial inequality is a fact of life in many Bermudian churches today, as it is in all aspects of Bermudian society, says Cordell Riley, president of Citizens Uprooting Racism in Bermuda (CURB), a group focused on combatting the island’s divisions. Racial disparities are especially evident in the financial discrepancies that exist between black and white, bred in part from advantages whites gained during segregation. There are more white homeowners than black, for example, and “voluntary segregation” based on wealth still happens in schools; if you’re a white parent, Riley says, there’s a 78 percent chance your child goes to private school, but if you’re black, there’s an 80 percent chance your child goes to public school.

While progress is coming, it’s slow, he says. “Participation by a church group could hasten that along.” Churches still play a major role in Bermudian life, giving church leaders an influential voice when it comes to fighting prejudice. The synod’s apology, Riley says, was a positive first move, but a first move all the same. “I think if they take that role, it has to be sustained, it has to be continued, and it has to have traction.”

Atwood himself agrees that the apology alone wasn’t enough. “It’s important not to rest on our laurels,” he says, and already the synod celebrated Black History Month in February to help foster a sense of inclusion. Taking a cue from Halliday’s report — which suggested the need for new black ministry personnel — the first Bermudian-born black minister was also appointed as a supply pastor at Ebenezer Methodist Church in St. George’s, not far from where Stephenson himself preached. Cyril Simmons started his position a month after the apology took place. “I believe it sets a course for the future,” he says of Atwood’s speech.

And as the church moves toward that future, racism is only one prejudice they hope to make right. During his speech, Atwood confirmed the Wesleyan Methodists’ commitment to continuing Stephenson’s “ministry to all” — no matter their race, but also irrespective of “political affiliation, religion, gender, sexual orientation or any of the categories that are sometimes used to divide or reject others.”

The inclusion of sexual orientation wasn’t by chance. Some churches in the conservative country have come out staunchly against homosexuality and the rights of the lesbian, gay, bisexual and transgender community. Discrimination based on sexuality currently isn’t prohibited in the Bermudian Human Rights Act. The synod, though, wanted to show that “our Gospel calling is to include all people, regardless of who they are,” says Atwood. He is planning to send a group to visit Bermuda’s Human Rights Commission, in an effort to find out how legislation excludes certain groups, including the LGBTQ2S+ population.

For the synod, it’s just the start in righting the wrongs that Stephenson himself was trying to right over 200 years ago. Leo Mills, for one, hopes actions like these will help make the church a role model in Bermudian society. “If the wider community looks at the church . . . and sees people there of different backgrounds, different races, different political parties, with different interests, get together around the cross of Jesus Christ, there’s a message — I think a very positive message — in that,” he says. “People will see ‘those Christians over there have got it right,’ and I think that’s a powerful lesson.”

***

This story first appeared in The United Church Observer’s July/August 2012 issue with the title “Another side of Paradise.”