Asked what it means to recover, Old Woman — the persona of a humble and wise elder in Richard Wagamese’s new book, Embers: One Ojibway’s Meditations — says this: “It is to be reborn. We arrive here covered in spiritual qualities like innocence, humility, trust, acceptance, and love. But things happen and those qualities get removed from us. Those qualities get churched off, spanked off, schooled off and beaten off. Sometimes we rinse them off ourselves with drugs and booze and poor choices.”

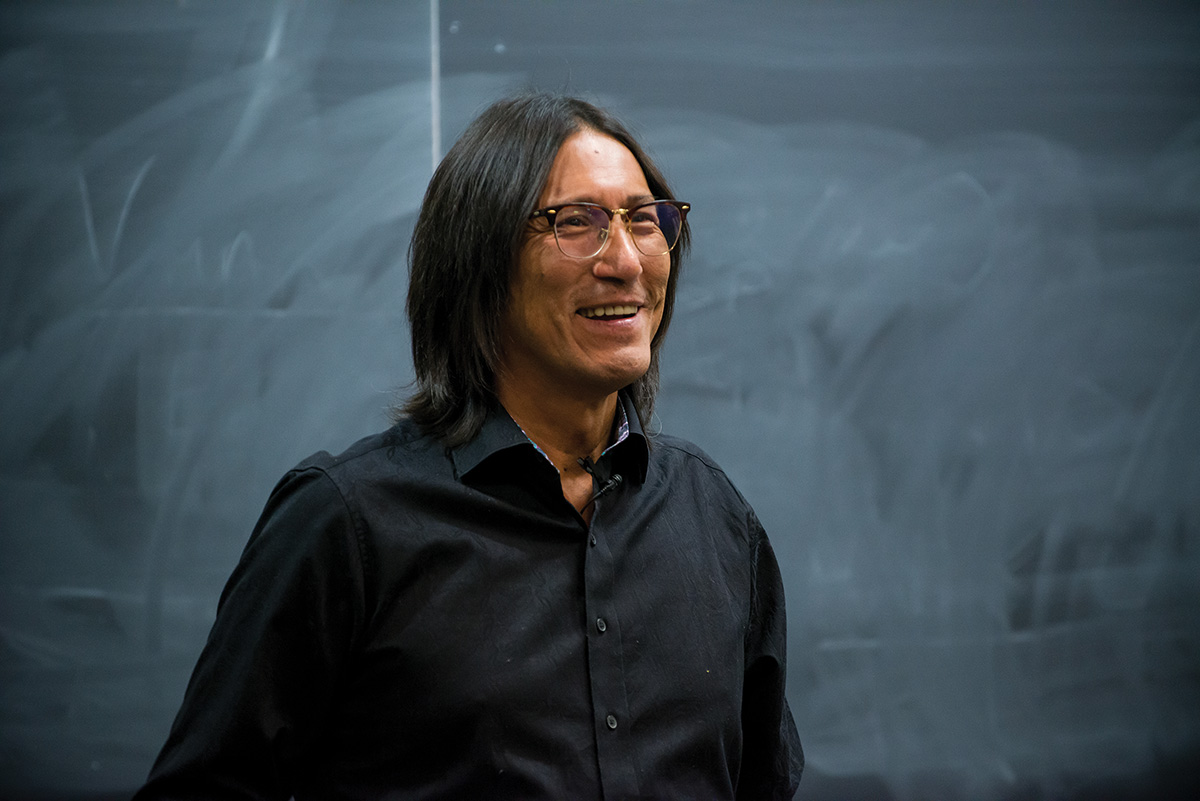

Wagamese knows what Old Woman speaks of here. Born into an Ojibwa family in the 1950s, he was taken from his northern community as part of the Sixties Scoop — a nationwide practice of “scooping up” Aboriginal children and placing them with primarily white adoptive or foster families. Always the outsider in the small city of St. Catharines, Ont., Wagamese felt culturally estranged for most of his life. He sought solace in alcohol and searched for companionship on the streets and later in prison. His path to recovery has been long and arduous, but somehow his brokenness makes his spiritual insights all the more brilliant. Now in his early 60s, Wagamese’s woundedness is part of his wisdom, his pain integral to his joy.

Readers of Wagamese’s fiction know that he is a storyteller equipped with a clear sensitivity for the spiritual ups and downs of living. While Embers, a collection of his personal reflections and insights, is nothing like his previous works, it is suffused with his trademark warmth, wisdom and way with words. Poetry is present on every page, guiding us toward both the Creator and gratitude for all of Creation.

His contemplations are printed on thick, glossy paper and paired with gorgeous images of the natural world — water, trees, animals, snow, sky and fire — that evoke his reverence for the miracle of life. The rich sensuality and spirituality of the reading experience will make you want to press this small book into the palm of everyone you know — to pass on this gift that Wagamese has given.

Embers is organized into thematic sections entitled Stillness, Harmony, Trust, Reverence, Persistence, Gratitude and Joy. It is particularly significant that Wagamese starts with Stillness. His book is grounded in the knowledge that the Creator becomes present in the silence between our words, that connections happen in the quiet. “It is in the splendour of silence,” he reflects, that we experience ourselves as “part of the great wheel of creative, nurturing, loving, benevolent energy that is spinning around us all the time.” Reverence for silence might seem strange for someone so devoted to building things out of language. But Wagamese is aware that the writer’s craft works best when it transports readers to what he calls those “small bits of silence” that allow “the surf of consciousness” to wash over us.

Wagamese’s meditations first emerged, as he relates in his introduction, in the silence of a morning ritual centred in the smudging bowl and the sacred medicines of his people. His embers, to borrow his metaphor, are drawn from the so-called tribal fire of Ojibwa spiritual practice and philosophy, such as the act of sitting and communing with one’s ancestors.

In its integration of Indigenous knowledge into a slim volume of spiritual meditations, Wagamese’s book shares much with Joyce Sequichie Hifler’s A Cherokee Feast of Days: Daily Meditations and Steven Charleston’s Climbing Stairs of Sunlight: A Spiritual Diary. Hifler delivers daily reflections in a blend of Cherokee and English, drawing on Cherokee songs, prayers and poetry, while Charleston, a bishop of the Episcopal Church and a citizen of the Choctaw Nation, draws on his dual traditions to offer teachings of hope and healing.

Taken together, these books challenge the reluctance among many Indigenous communities to write about sacred spiritual teachings, traditionally passed down orally through elders. But as Noel Starblanket notes in his foreword to Blair Stonechild’s The Knowledge Seeker: Embracing Indigenous Spirituality, there is a hunger among younger generations of First Nations people to learn about teachings that were nearly wiped out.

Stonechild, a Cree-Saulteaux professor of Indigenous studies at First Nations University of Canada in Regina, recognizes that colonialism has profoundly damaged what were once strong spiritual traditions. He situates The Knowledge Seeker — which delves into sacred teachings and laws on the purpose of Creation — within a larger project of spiritual recovery. Citing the final report of the Truth and Reconciliation Commission, which recognizes that residential schools interrupted the transmission of Indigenous spirituality, Stonechild shares this knowledge with the permission of elders who acknowledge that such a task is imperative in the face of widespread erasure. Still, the hesitance of other elders to disseminate spiritual teachings seems reasonable given historical persecution by governments, churches and schools — a history that Stonechild retells from his perspective as a residential school survivor, Indigenous activist and scholar.

Non-Native readers of Stonechild and Wagamese may initially feel compelled to reduce Indigenous spirituality to its points of connection with Christianity. After all, Indigeneity and Christianity share common ground: belief in a loving Creator; values of respect, humility and compassion; a tradition of living faith through stories and ceremonies. But they are also marked by important differences in stories and ceremonies, and imbued with distinct ideas of cosmology and Creation.

As elements of Aboriginal spirituality increasingly make their way into mainstream settler discourse, we need to keep discussing the capacity for diverse spiritual traditions to co-exist, and remain vigilant about missteps leading to yet another act of colonial assimilation.

Reading Wagamese’s Embers begs the question of how to engage dialogue between Christianity and Indigenous spirituality. In other words, how can we create what Cree philosopher Willie Ermine calls an “ethical space of engagement,” a space where Christian and Indigenous teachings mutually inform one another? For Christians, the value of engaging with Indigenous teachings is in seeing the Creator as fully present in all of Creation. As Wagamese writes, “Teachings come from everywhere when you open yourself to them. That’s the trick of it, really. Open yourself to everything and everything opens itself to you.”

This story originally appeared in the January 2017 issue of The Observer with the title “Break with tradition.”