Around 9:30 p.m. on a balmy night in Calgary, Simon Bondoc left the only life he had ever known. Under a star-speckled sky on Sept. 21, 2019, he pulled his car door shut and took deep breaths to settle his nerves. He remembers turning the engine on, air conditioning blasting as he sat with his thoughts. Ten minutes later, Bondoc pulled out his phone. Swiping to Instagram, he trained the camera on his face and held down the button to record. “So one of the hardest decisions in my life has just come to its full closure,” he said. “I’ve left my church of 14 years.”

He was idling in front of a fellow churchgoer’s house after saying goodbye to his favourite pastor and other church members at their Bible study gathering. Before Bondoc left, they all said a prayer to wish him well on his new journey.

You may unsubscribe from any of our newsletters at any time.

Leading up to this farewell was “a lot of uncertainty” about what came next, Bondoc says. The 23-year-old Filipino Canadian had attended a predominantly Filipino evangelical church in the Christian and Missionary Alliance since he immigrated to Calgary from the Philippines when he was seven. His mother is a longstanding member of the congregation, and he recognized everything that he was leaving behind in the church. A community he had known since he was a child, for one, and a tie to his culture. Yet he also knew he could not stay.

Breaking away from his church was one of the biggest decisions he had ever made, but Bondoc was steady in his resolve. “It felt like I cleared through something,” he says. That night in his car, before he pulled back onto the road and headed home to confront the questions clouding his future, he was at peace.

With that choice, Bondoc joined a long line of young Asian Canadians who have left the church communities they grew up in. A 2019 Ontario-wide study looking at Asian Canadian Protestant young adults found that 44 percent no longer attend their churches. Reasons for departure vary, but those leaving are illuminating a generational and cultural rift in monoethnic and culturally specific church spaces.

A 2011 journal article on the Italian Canadian Pentecostal community identified a similar pattern. Though these churches often start as “ethnic enclaves,” later generations tend to forgo exclusivity and “meld into the wider culture.” But some second-generation Asian Canadians do not want to part with their faith entirely. So after they leave, they must figure out where to go next.

In Canada, immigrants from Asian countries faced decades of systemic racism. In 1923, the Chinese Immigration Act passed, effectively prohibiting most Chinese immigrants from coming to Canada. Even after the act was repealed in 1947, rules still limited immigration of “Asiatics,” including those from Middle Eastern countries. It wasn’t until the 1960s that the last vestiges of anti-Asian immigration legislation were removed.

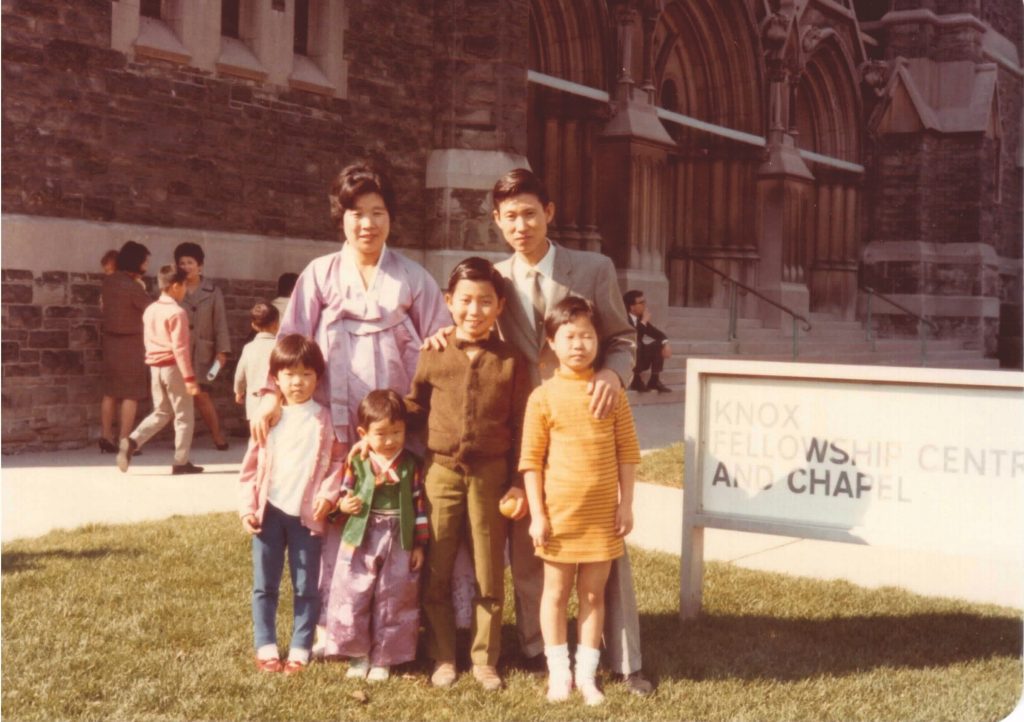

In 1965, among the first communities established by the newly arrived populations in Canada was a Korean United church in Vancouver. Since then, the number of Asian congregations in Canada has ballooned. By 2006, for example, there were approximately 350 Chinese Christian churches across the country.

But in 1996, a new term sprang up: the silent exodus, which Helen Lee popularized in a Christianity Today story. She was describing the emerging trend of young Asian Americans who were leaving their churches. “The second generation is being lost,” Allen Thompson, a co-ordinator for multicultural church planting in the Presbyterian Church of America, told Lee.

It wouldn’t surprise most Canadian churchgoers to learn that younger adults generally — even those raised in the church and from non-immigrant families — are less likely to be members today. A study commissioned in 2011 by the Evangelical Fellowship of Canada found that only one in five Catholic and mainline Protestant Canadians who attended church at least weekly as children in the 1980s and 1990s con-tinue to do so now.

This phenomenon has also been recorded in ethnically Asian churches, albeit unevenly. Asian American church leaders estimated in the 1990s that attrition rates from their congregations ranged from 70 to 90 percent. More recently, though, researchers have been challenging that narrative.

Nam Soon Song was the Ewart professor of Christian education and youth ministry at the University of Toronto’s Knox College when she retired in June. She questioned the so-called silent exodus in a 2019 study. Song surveyed 300 Protestant Asian Canadians, ages 17 to 29, who were either born or living in Canada before age 15 and had attended a church during their high school years. Eighty-one percent had attended their own ethnic church, while the remaining participants attended mostly Caucasian or mixed-ethnic churches.

Song’s study was conducted in two groups. The first was made up of 191 people who completed the survey on university campuses; their status as churchgoers was unknown to Song at the start of her research. The second group, of 109 participants, were church members surveyed in a church. Segmenting the participants in this way helped her better understand what drove young Asian Canadians to either stay or leave their churches.

Song found that of the university campus participants, only 44 percent had split from their churches. The rest stayed on to preserve their connection to religion and a cultural community. But her most striking finding was that many of those who had broken away from the church were still connected to their faith. According to her study, almost half of all non-attendees continued to practise some type of “spiritual life,” such as praying or reading the Bible.

In an interview, Song explains that while members of the second generation tend to be more progressive than their predecessors, religion still holds special meaning as a tether to their cultural identity. Instead of a silent exodus, she considers it a silent moratorium.

Rev. Daniel Cho never had a problem with faith, but he did have a problem with how his Korean church interpreted it.

A 56-year-old Korean Canadian, Cho is now the senior minister at St. Mark’s Presbyterian Church in Toronto. When he was two years old, his family moved to Toronto from Korea, and he attended Central Korean United until the end of high school. After some schooling in the United States, he returned to Toronto and worked with various Korean congreations — before leaving in 1999. “Growing up, the main message that got hammered into us all throughout Sunday school, junior high and even youth was you’re Korean first,” Cho recalls. “And Christianity helps you to be a better Korean.”

Central Korean United entered its heyday in the 1970s. With a congregation of more than 600 people, it was a major community space for the city’s Korean population. “During that time, there was continuing immigration,” Cho says. “So the Korean church was constantly being reinforced with Korean culture.”

In the 2016 census, there were reportedly 198,210 people of Korean origin in Canada, and the 2001 census estimated that approximately three-quarters of Korean Canadians identified as Christian.

Cho was part of the early wave of Korean immigration in the 1960s. In the 1980s, as he and his second-generation peers entered their high school and university years, Cho witnessed the exodus at Korean churches. Though his faith held steady, his friends became disillusioned. Some no longer felt connected to Christianity, and others questioned the way it had been taught in their ethnic spaces.

Cho says second-generation congregants turned away from the “childish way…of thinking about God” espoused by some Korean churches, eventually leaving them altogether. Nam Soon Song’s study also found that those aged 21 to 22 are especially prone to leaving, showing the highest attrition rate.

Cho’s rift with Korean churches was a slow burn. As he rose in their ranks, he began to feel that those in charge were more interested in maintaining their influence than teaching meaningful theology.

He calls it a “Sunday-school mentality.” People came to church to be reminded of how blessed they were and how many more blessings were waiting in the wings. The rewards of faith, it sometimes seemed to Cho, boiled down to getting a raise and a nice car.

He wanted to teach people the nuances of a less self-serving religion, but his ideas faced pushback. In Korean culture, respect for elders is paramount, and even though Cho was technically equal to other ministers in title, he was also the young man in his early 30s openly spurning their teachings.

After he concluded the people in power in his Korean church were not interested in giving the second generation any agency or leadership, he left the community altogether. He found new opportunities elsewhere in non-Korean churches where he could build meaningful connections with his congregations.

Song’s research confirmed the importance of leadership in church retention among Asian Canadians. Her survey respondents on university campuses were much more likely to stay with the church if they had participated in praise teams, for example.

Though Cho was given authority at his church, he felt unable to enact real change. He recalls one conversation in which a senior minister from from the last Korean church he worked at told Cho that he and all other second-generation Koreans should follow the instruction of their predecessors. Without any first-generation members to guide them through their culture and faith, the senior minister said, they are directionless, tethered to nothing, like balloons suspended in mid-air.

To illustrate his point, the senior minister lifted his hand in front of Cho’s face and dangled it by the wrist, fingers turned downward.

On a stuffy Sunday morning in July 2016, Rachel Chen listened to a sermon that struck a nerve. In Plano, Texas, the 25-year-old Chinese Canadian sat in a Chinese American church she had attended for years after moving from British Columbia. Earlier in the month, Micah Xavier Johnson, a Black veteran, had shot 12 police officers, killing five during a Black Lives Matter protest in Dallas after voicing his frustrations over anti-Black police brutality.

The pastor began by saying that there were some important current events to talk about. The line piqued Chen’s interest — her ethnically homogenous congregation didn’t often speak about racial issues. As a community, the pastor continued, we really need to support the police. And then for Chen, it all fell flat.

The pastor emphasized the importance of respecting the police, especially after the shooting. Chen empathized with the tragedy, but she couldn’t understand why the pastor framed the issue without discussing the systemic racism that preceded it.

The week after, she sat in on another sermon on the same subject — this time, at a friend’s multicultural church. Chen remembers looking up in awe at a Black pastor who spoke about reconciliation and the ways anti-Black racism hurts everyone in the church.

Rachel Chen split from her Chinese congregation because her progressive values weren’t reflected in the church. (Photo by Stephanie Bai)

Though these were not the only events that precipitated her eventual departure from the Chinese church community, Chen began to think about church differently. Maybe having a congregation that shared one culture meant existing in a bubble. Maybe the exclusivity of ethnic churches could insulate them from the rest of the world. “I don’t know if we should make faith spaces like that,” she says. “They didn’t really acknowledge race because they didn’t have to.”

Chen’s disillusionment was reflected in Song’s 2019 study. It found that when the church’s teachings don’t align with the values and experiences of second-generation Asian Canadians, this becomes another significant reason for their departure. But Chen understands how these communities came to be.

The Chinese Canadian Christian population is smaller than that of many other ethnicities; in the 2001 census, only an estimated 23 percent of Chinese Canadians reported being part of a Christian denomination. And after more than a century of discrimination against Asians in Canada, it makes sense that some Chinese Canadian Christians would turn inward for safety.

Since the COVID-19 pandemic started, research in major cities has found that reported hate crimes against Asian Canadians were significantly higher than in the previous year. The Chinese immigrant community in particular has faced vitriol over racially inflamed claims that they are all carriers of COVID-19 or entirely to blame for the pandemic. The importance of relief and safety found in shared cultural spaces like ethnic churches can’t be understated. “That’s something I’ve complicated now,” says Chen.

Although she knows why the Chinese Christian community often remains exclusive, as a queer woman who backs multiculturalism, Chen doesn’t usually see her own values reflected in its teachings. She’s still looking for a church to attend. After moving back to Canada and sampling a mix of congregations, she says none have stirred the instinctive sense of belonging she’s sought for years. It’s difficult, says Chen. “You go where it’s comfortable. But then sometimes, it’s too comfortable.”

In one month, Simon Bondoc took two of the biggest steps in his life. Near the end of September 2019, he left his church. A few weeks earlier, on the first Sunday of the month, he walked in a Pride parade.

September 2019 will always be bookended by these memories: the parade he marched in with other Filipinos and the night of farewell. “It felt really comforting knowing that I may have left one side of the community, but there’s also another side of the community that is there for me,” he says.

Bondoc realized he was queer around 11 years old. He can’t pinpoint the first time that he heard anti-gay sentiments, but the Alliance Church has always enforced a traditional view of sexuality and marriage, rooted in similar values in Filipino culture. Whenever he heard a minister or teacher say the words “gay” or “same-sex marriage,” his entire body would go rigid.

So he kept his secret for almost a decade, his faith warped by fear. “I grew up with needing to hide who I truly am,” Bondoc says. “I used religion as a mask.”

Song’s study showed that people’s unhappy experiences with church life were one of the top drivers for breaking away from the church. Citing a participant who was marginalized for her sexual identity, Song emphasized that some departed after facing “broken and hurtful” surroundings in their congregations.

In a 2013 study of 40 gay Filipino and Latino second-generation men in California, a majority of whom were raised Catholic, only two still practised their faith.

Leaving the church came at a cost for Bondoc. His departure initially strained his relationship with his mother. While he was firm in his choice to leave, she wanted him to stay. She remains in the church to this day.

Bondoc also grieves the loss of his cultural ties. Filipino Canadians come from a strong religious tradition; the 2001 census found that approximately 96 percent of the community identifies as Christian. Culture is often inseparable from faith. Even today, when he thinks about the Tagalog spoken at gatherings, the smell of Filipino food at Bible studies or the bright sound of laughter in church groups, it hurts.

“I did ask myself that question a lot: Okay, if you leave, you will lose the sense of community, but is it for your betterment? Is it for the good of you personally? And I said yes.”

Eventually Bondoc found his way to Central United in Calgary. Working through his religious trauma, he’s learning that love, not fear, drives his faith. He’s thinking about becoming a minister to help others realize that as well.

“There are people out there who are marginalized in my community that deserve their cultural connection, that deserve the community that is affirming of them,” he says.

He knows it’s possible. He’s seen it first-hand at his current queer-friendly church with a sizable Filipino membership. But he also knows everything it took to get there. Sitting in the car on that warm September night in 2019, Bondoc never could have guessed this is where he would end up, but he made peace with who he wanted to be. And that fullness was lighter than expected.

“It was really hard at first,” he says. “Also, at the same time, it was very, very freeing.”

Stephanie Bai was one of Broadview’s summer interns and is a student at the University of Toronto.

This story first appeared in Broadview’s January/February 2022 issue with the title “A different path.”

I attended the church in Vancouver mentioned in this article. The Korean congregation bought their own church 20 years later. The Korean minister wrote beautiful poetry. I Facebook and sing with one of his daughters.

Young people and old are leaving the Church because there is no longer love present. I’m a Marginal Mennonite but member of none.

On the first day of the Week of Prayer for Christian Unity, the decision to republish this piece on Christian disunity seems intentional and insulting to those who came together to pray for unity. Although critical, a piece on how leaving one Christian community for another affects ecumenical relations would fit better with the spirit of the week.