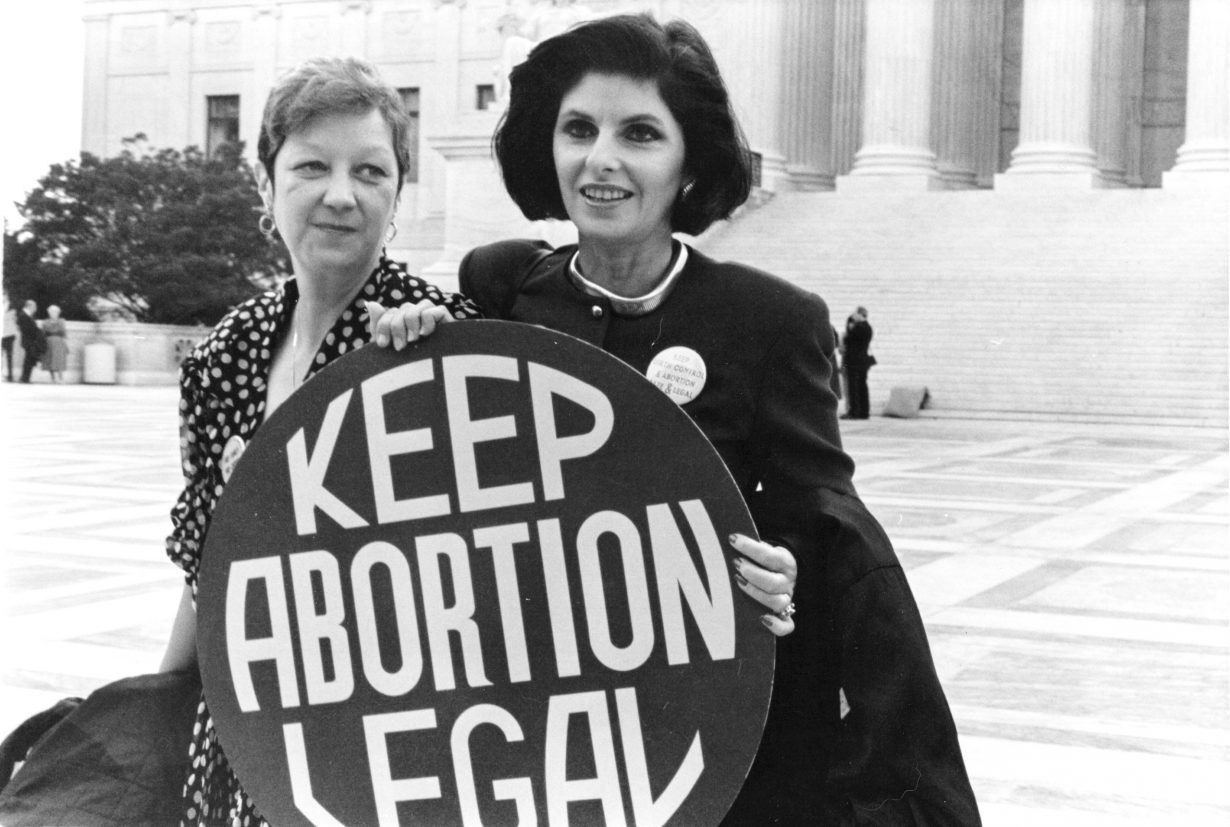

Norma McCorvey has dropped a lot of bombshells in her life. In 1973, she came out to the press as Jane Roe, the plaintiff in the landmark American reproductive rights case Roe v. Wade. In 1987, she spontaneously admitted during an interview that she had lied when she’d claimed that the pregnancy that led to Roe v. Wade had been the result of rape. Then, in 1995, after a decade of pro-choice activism, she was baptized as a born-again Christian and became an outspoken critic of abortion. In 2020, three years after her death, she had one last big reveal in the documentary AKA Jane Roe, which was filmed during her final months and released this past spring: her anti-abortion activism had all been “an act” for which she’d been paid. If nothing else, this “deathbed confession,” as she described it, marked an impressive end to a lifetime of chameleon-like transformations.

AKA Jane Roe is one of several films to come out in the first half of 2020 on the topic of reproductive rights. Others include The 8th, a documentary depicting the fight to overturn the incredibly restrictive abortion ban in Ireland, and Never Rarely Sometimes Always, a feature-length drama about an American teenager seeking to end her pregnancy. All three contribute meaningfully to the conversation about reproductive justice, and, although they are not all American-centric, each feels timely in its own way, especially now as the death of U.S. Supreme Court Justice Ruth Bader Ginsburg puts the future of Roe v. Wade in question.

More on Broadview:

- Why P.E.I. didn’t provide abortions for 35 years

- Katherine Hancock Ragsdale on the fight for reproductive justice

- New film sheds light on forced adoptions in church-run homes

The 8th is the strongest of the three films, though that might be in part because its crisis arc comes with such a powerful, historic resolution. The documentary traces the pro-choice movement in Ireland from the 1983 passage of the Eighth Amendment of the Constitution, an act that granted “the unborn” an equal right to life as pregnant women, up to the referendum to repeal it in 2018. Directors Maeve O’Boyle, Aideen Kane and Lucy Kennedy have clearly poured a lot of love into the film, which weaves in the reflections of present-day activists on both sides of the issue with archival footage of various reproductive flashpoints in the country. These include the tragic story of Savita Halappanavar, who died of sepsis in 2012 when doctors refused to terminate her pregnancy after an incomplete miscarriage, and the abuse inflicted on unwed mothers and their children at Catholic institutions.

The filmmakers’ care is also evident in their interviews with anti-abortion activists, many of whom come across as thoughtful people rather than dogmatic hardliners. One woman in particular describes her own experience with a friend who died by suicide after travelling to England for an abortion, and how she worries that the focus on pregnancy as a problem to be easily dealt with will divert resources and attention from mothers who are struggling to get by. Although her conclusions are a bit specious (she doesn’t seem to consider the fact that maybe it wasn’t the abortion itself that traumatized her friend but the culture of shame and secrecy that she returned home to, or that many pro-choice activists are engaged in other forms of activism to elevate marginalized groups), she’s shown as being pro-life in the full sense of the term.

While the on-camera subjects are all compelling, The 8th’s emotional heart isn’t their interviews, or the footage of young Irish women flying home in droves to vote, or even the positive outcome of the vote itself. Instead, it’s a short segment shown just before the footage of the day of the referendum. Over breathtaking aerial shots of the country, anonymous women narrate the stories of their abortions: the anxiety they had about travelling out of country for the procedure; the grief of hearing a doctor tell them their wanted child had fatal fetal abnormalities, but they must continue carrying the pregnancy; the fear they felt while taking black-market abortifacients; and their absolute shame and horror that they might be caught and revealed to their family and friends. But while there are parts of The 8th that will no doubt leave many viewers in tears, overall it’s a joyful film, proving what grassroots organizing can achieve.

By contrast, the tone of Never Rarely Sometimes Always is much grimmer. Faced with an unwanted pregnancy, 17-year-old Autumn Callahan has nowhere to turn. The main resource in her small Pennsylvania town turns out to be a crisis pregnancy centre, and after a predictably negative experience there, she learns that minors can’t obtain abortions in her state without parental consent. She and her cousin decide to travel to New York City together so that she can terminate her pregnancy, stealing money from the supermarket where they both work to pay for the bus tickets. Once there, Autumn visits a Planned Parenthood clinic, where she’s dismayed to discover that her pregnancy is further along than she’d realized and requires a two-day procedure that will have to be performed at their Manhattan clinic. During her interview with the counsellor, we learn that several, if not all, of her partners have been abusive, and the pregnancy is the result of coerced sex.

Never Rarely Sometimes Always can at times feel didactic, like its message is driving the plot and characters rather than letting them unfold organically. That being said, director Eliza Hittman has delivered a beautifully shot film with tight, well-written dialogue. Sidney Flanigan is astonishing as Autumn. If nothing else, it’s an exquisite demonstration of how abortions are made to be harrowing not because of the procedure itself, but because of all the dangerous and seemingly impossible barriers people have to overcome to obtain them.

AKA Jane Roe is perhaps the trickiest to unpack of the three films. It’s hard to know at what points Norma McCorvey is a reliable narrator and at what points she’s skirting the truth (or, perhaps more accurately, has created her own version of the truth). What’s clear is that she felt used by both the pro-choice and pro-life movements, although she was able to wield her work with the latter more to her advantage. She was a complex woman who came from an abusive family and struggled throughout her life with poverty, substance abuse and toxic romantic relationships. What she was looking for seems to have been love and acceptance, though it ultimately came at a high cost both on a personal level and on the much broader level of the credibility of the reproductive justice movement. Filmmaker Nick Sweeney delivers a balanced, if sometimes troubling, account of a life that has had an outsized impact on abortion in the United States.

All three films are important, each highlighting a different aspect of why the fight for reproductive rights is so important and so unfinished. If there is one take-away from all of them, it’s that severely restricting abortions will not stop them from happening — it will just endanger vulnerable lives. No one has ever been empowered by having choices taken away from them, but plenty of people have been, and continue to be, harmed.

This essay first appeared in Broadview’s November 2020 issue with the title “Abortion stories.”

Anne Thériault is a freelance writer in Toronto.

We hope you found this Broadview article engaging.

Our team is working hard to bring you more independent, award-winning journalism. But Broadview is a nonprofit and these are tough times for magazines. Please consider supporting our work. There are a number of ways to do so:

- Subscribe to our magazine and you’ll receive intelligent, timely stories and perspectives delivered to your home 10 times a year.

- Donate to our Friends Fund.

- Give the gift of Broadview to someone special in your life and make a difference!

Thank you for being such wonderful readers.

Jocelyn Bell

Editor/Publisher

Roe v Wade could be repealed by the Supreme Court of the U.S. in the near future. Trump has succeeded in loading SCOTUS with ‘conservative’ members.

What a rather simplistic view. Even if RvsW was reversed it does not make abortion illegal. It kicks the decision to the individual States to decide on the issue of weighting the right to life over the right to end life.

To paraphrase something I believe Ronald Regan once observed, I notice that everyone who supports abortion had already been born.