I started to pray when I learned my wife, Jocelyn, was pregnant. She did, too. We held hands every night and called down to the bottom of that deep, dark well where the little ember that would be our child clung. I had long ago given up praying to a God who might look kindly upon me if I said the right words, so instead I peered into that black space beyond my mind and implored: “Hold on, Bubs. Be well. Stick around.”

They don’t tell you that brand new fetuses are as likely to die as not. The chance of miscarriage in the first two weeks can be as high as 75 percent, if you trust a statistic commonly reported on the internet. Most of the time, the mother will never know she has miscarried. The risk falls quickly, but by the time we confirmed the pregnancy, it was still a chilling 43 percent, according to an online miscarriage probability chart that my wife and I studied nightly. It was a masochistic exercise, but we couldn’t resist. Even as the risk continued to drop, I never shook the feeling that the baby was coming to us from the other side of life, and could just as easily turn around and go back.

You may unsubscribe from any of our newsletters at any time.

After trying to conceive for more than a year and already miscarrying once, it felt right to perform the concentrated, half-crazed hoping that people call prayer. To will an unselfish good, by whatever powers exist in the universe, is an antidote to personal powerlessness and a balm for fear. For that reason, I also started to pray for Mother Earth. It seemed to be the only activity that could contain the terrible feelings I was having about the ecological calamities looming over our planet, a crisis that seems to worsen with each passing day.

I soon realized I wasn’t very good at praying. I thought I might do better with other people around, so I asked a nearby church if I could borrow their space to hold prayer meetings for Mother Earth. But I was told the church could not afford to make its facilities available to people who weren’t prepared to pay to use them. “We can no longer permit ourselves any charity,” I was told. “It is us who need charity.”

I now think I might have been asking too much of prayer. For not only did I want our prayers to protect the fetus in Jocelyn’s womb, I also wanted them to address a question that troubled me more deeply the more the pregnancy advanced: why would anyone want to bring a baby into the world in these times? If there were answers hidden in the silence that greeted my prayers, I couldn’t find them.

Before we conceived, the womb always struck me as a relaxing place: no responsibilities, nothing to do — just a hot sack in which to wait for life to start.

After we conceived, an app on my phone kept me abreast of fetal development, marking each week by comparing the growth of the fetus to the size of a fruit or vegetable, and I came to realize that life in the womb is less like an amniotic trance and more like a psychedelic wormhole of ceaseless, mind-bending novelty. From the get-go, the fetus was sprouting appendages and vital organs on fast-forward, logging an average of 250,000 new nerve cells every minute. Jocelyn’s womb was like a hyperspace accelerator, capable of turning a non-existent nothing into a multi-dimensional being.

During its journey across the murky edge of reality, a fetus is a tiny traveller belonging to another world: not the upside-down, but the in-between. For most of its time in the womb, its skin is translucent, like a jellyfish rising up from the darkness of the ocean, sometimes sinking back down.

Our perception of the fetus’s fragility changed at eight weeks, when Bubs was the size of a raspberry and just developing lips and eyelids. That’s when we went for an ultrasound.

We’d been going to a fertility clinic for almost a year by that point, and these trips always made us giddy. We would treat ourselves to McDonald’s on the way in and joke like kids in the reception room. On this particular trip, our giddiness ended when the technician arrived and waved her wand. Suddenly, a humanoid form materialized from the grey fuzz on the screen. Its tiny heart pulsed like a distant star. We gasped. “That’s the beat! Oh my God, you can see the heart!” Jocelyn exclaimed. “Oh shit!” I shouted, pointing at the screen. I pressed in to get a better look, and the technician asked me to move out of the way.

But it proved to be a bittersweet moment, because just beside our little person was the body of another, whose journey had ended only a week or two previously. “You can see there were two,” the technician said, pointing at the tiny dark shape. “It’s dead?” Jocelyn asked. “Yes, it stopped,” the technician replied, gently.

My happiness at having one living baby on the way couldn’t be dislodged, but at the same time I felt sad for our little somebody, whose first experience of life was to lose a twin. Had it registered, the other berry? Had a friendship begun in the darkness, before it stopped? That evening, I tried talking into Jocelyn’s belly, to say something cheerful and reassuring, but all I could think of was “Hi!”

More to read: This is the world our children will inherit, and it’s not looking good

A long time ago, the world was covered with oceans, and the oceans were full of algae, which filled the air with oxygen so animals could live here, like us. The algae absorbed light from the sun, and when the algae died, they took the light deep into the earth, where they stored it as energy. For hundreds of thousands of years, humans lived on the land, never guessing that all that energy was down there. But then we found it, set it on fire and the fire become our superpower. We flew through the air, turned night into day and built giant robots for our service. But by burning it, we released a gas into the air that quickly covered the Earth, like a blanket that we can never remove. And even though we’re starting to bake under the blanket, we can’t stop using our power. The blanket is getting heavier and heavier, and we’re getting hotter and hotter, but even so, we can’t seem to stop.

Something like that.

Only a few weeks after we conceived but before we knew we had, I travelled to the Saint John River in New Brunswick, where a record-setting spring flood had damaged thousands of dwellings a few months earlier. By the time I arrived, all the wrecked and rotting buildings had been removed, while the rest were in various states of repair. As I toured one community hit hard by the flood, I happened across a stone fireplace standing alone in the middle of a small plot of land overlooking the water, like a snail that had lost its shell.

Talking to neighbours, I learned that an old cottage had stood in that flood plain for half a century. It had always seemed impervious to floods. But it was no match for the flood of 2018. By the time the clean-up crews were done, only the fireplace remained. Some odds and ends had been placed inside it — a pair of pliers, a toy tractor, someone’s keys, a small wooden sign that read “No Vacancies.”

The image of that fireplace haunted me the rest of the summer — including the morning a few weeks later when Jocelyn and I stood shoulder-to-shoulder in our tiny Montreal bathroom staring at two pink lines in the little display window of a pregnancy test device, and the next five mornings when we repeated the test, still not quite able to believe it was registering positive. The fireplace symbolizes hearth and home, but that one in New Brunswick felt more like a shrine to an era we never believed would end. Or maybe more like an altar for the time that has now come, with more powerful and more frequent storms; with more people displaced by floods and forest fires and droughts; with hotter days and rising waters; and with our child in it, figuring out who and how to be.

The heartbeat exploded through the receiver. “Is that it?!” I called out, and I heard Jocelyn reply, “Yes,” in the voice she makes when she’s crying. My eyes instantly filled with tears.

We stopped praying when we actually heard a heartbeat for the first time. It was just too good.

It happened when the fetus had grown to about the size of a lime. I was out of town, so Jocelyn called me from the doctor’s office where she was having another ultrasound and put me on the speakerphone. I was cradling my phone against my cheek, trying to catch every noise, when the doctor placed the doppler wand on Jocelyn’s stomach. “It can take a few minutes,” she started to say, when the heartbeat exploded through the receiver. “Is that it?!” I called out, and I heard Jocelyn reply, “Yes,” in the voice she makes when she’s crying. My eyes instantly filled with tears.

Even through a tinny smartphone speaker more than 500 kilometres away, I’ve never heard a more vibrant sound than that baby’s heart — like the rumbling boulder that tried to crush Indiana Jones. “This thing is happening!” I realized with a jolt. There no longer seemed to be any point in praying for the baby to live; it would be like asking a speeding elephant to run faster.

But even as my paternal anxieties were replaced with pleasure and excitement, my existential fears about the fate of the planet were growing noisier. They had taken on a new urgency with the news that Jocelyn was pregnant, and began to follow me around in the daytime, and shake me awake at night. Worsening news seemed to greet each stage of fetal development.

The fetus was seven weeks and the size of a blueberry, sprouting nubby little arms and legs tipped with webbed hands and feet, when United Nations Secretary-General António Guterres warned that climate change represents a “direct existential threat” and that “we are careening towards the edge of the abyss.” A month later, when the fetus had grown to about the size of a strawberry and its vital organs were all newly functioning, the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change warned that if we hit 1.5 degrees of warming, most inhabited regions of the Earth, particularly the tropics, will see increases in the number of extreme hot days. Some places will see more precipitation, others more droughts. Unless things change in some dramatic and perhaps unlikely ways, my baby and I will witness the melting of the polar ice caps.

The fetus was about as large as a pomegranate and growing eyebrows and eyelashes last January when RCMP officers crossed a barrier on a logging road in British Columbia, in the territory of the Gidimt’en clan of the Wet’suwet’en First Nation, and arrested 14 people who were protesting a proposed $6.2-billion natural gas pipeline. A few weeks later, a study by the American Geophysical Union reported that the release of carbon dioxide and other greenhouse gases into the atmosphere is happening nine or 10 times faster than during a period when palm trees grew in the Arctic and acidification and oxygen depletion caused mass extinctions in the oceans.

By the time the fetus was the size of a cauliflower and starting to smile, news media were reporting on a scientific review that warned of an insect Armageddon caused by overuse of pesticides, urbanization and climate change. Insects are rapidly going extinct, threatening no less than a complete collapse of nature. “Unless we change our ways of producing food, insects as a whole will go down the path of extinction in a few decades,” the authors of the report concluded. “The repercussions this will have for the planet’s ecosystems are catastrophic to say the least.”

When I should have been reading guides about birthing and early childhood development, I was drawn to Sheila Heti’s 2018 book, Motherhood, because I was dogged by the question of why I desired a child, even if it meant bringing it into a world of growing peril. Heti’s book is ultimately about not wanting to parent.

My own desires are clear: I want to re-experience the world from the perspective of my child; I want to be filled with a greater and more selfless love; I want to advance to a new stage in life; I want Jocelyn to be fulfilled in her wish to be a mother; I want to obtain the social benefit of fatherhood; I want to take care of someone and make them feel safe; I want a cute and interesting friend to do fun stuff with; I want to walk very slowly down the street beside someone with tiny legs. And so on.

But, as Heti’s book reasons, desire itself doesn’t negate the moral mathematics of conceiving. “There is no inherent good in being born. The child would not otherwise miss its life,” she writes. “Nothing harms the earth more than another person — and nothing harms a person more than being born.”

She’s right about the “harming the earth” part. The most effective action for fighting climate change is to have fewer children. A 2017 study reported that having one fewer child equates to 59 fewer tonnes of carbon dioxide emissions for each year of the parent’s life. The next best thing — living car-free — only reduces carbon emissions by 2.4 tonnes per year.

Evidently, I’m not alone in wrestling with the question of bringing more children into a warming world. Last summer, the New York Times released the results of a poll about why Americans are having fewer children. One-third of respondents cited climate change.

Ultimately, I convinced myself that whatever happens to the world, it will still need good people. But if I were to be completely truthful, I’d say the biggest reason for having a baby is that we wanted one.

“Nothing harms the earth more than another person — and nothing harms a person more than being born.”

Sheila Heti in “Motherhood”

As I drew nearer to fatherhood, I found myself wondering about what is really real. Back when I was simply becoming a man, I thought of reality as something heroic. I read T.S. Eliot’s line, “Human kind cannot bear very much reality,” and I thought, “Exactly!” Later, when I entered that ugly period that some men go through in their 20s, and others never leave — when greatness escapes us and goodness does not come easily; when we become martyrs to our disappointment — I lost interest in reality, and got stoned a lot. But now that I had participated in stewarding a new human into existence, I began to think more carefully about the stuff of living. One wintry day, after filing long-overdue income taxes, a thought settled in my head like a stone dropped into a pond: I belong here, and that means I’m not free. I’m accountable for the space I take and for what I use. I have to do my part and pay my share. I receive so much, and so I must give what I can. Not to be a good person, but simply to be part of this world. When my child arrives, my life won’t be mine anymore. But the fact is, it never was.

Another day, I met a bird researcher at a photography class. He was there to take better pictures of the birds he captures live, in what he described as large volleyball nets. I mentioned an article I once wrote about bird strikes — when birds get confused about a reflection in glass and crash into windows.

“Yeah, the bird world is very tragic,” he said. “Their populations are tanking.” We were walking into the metro as he said this, and at that moment he swiped his card and found that he had run out of funds. “Nice to meet you!” I called out as he went back to refill it.

These days, moments of sudden bleakness seem to occur almost offhandedly: “The birds are all dying.” “Okay, bye!”

Later that same week, I watched a video about Arctic amplification — the process whereby Earth’s north pole is heating much faster than everywhere else. The researcher said, if we keep going as we’re going, there won’t be any ice left in the Arctic in the summer by the middle of this century. In other words, by the time our baby is my age.

That night in bed, I shared this with Jocelyn. We stared at the ceiling. “Let’s go,” she said. “I want to go to the Arctic.”

A while later, I attended an ecological grief circle at McGill University. Nine people, most in their early- or mid-20s, sat on the floor in a circle. We introduced ourselves and, over the next 90 minutes, shared our feelings about the end of the world.

When it was my turn to pick up the little wooden mushroom that stood in for a talking stick, I told the group that I was having a child and I was freaking out about it. They nodded knowingly, but I did not believe they really understood. I remember my 20s too well. Back then, my life was constantly changing, and I came to believe I had the power to move around and start over at will. Unconsciously, I thought society should be like me — easily transformed. I did not yet know that the best things need stability and security to grow. I felt the need to tell the group, “I like society. I want it to be okay.”

As the evening continued, I realized that most in the gathering held a much bleaker outlook than I did. I had thought I was taking climate change pretty seriously, but here were people for whom impending ecological and societal collapse was a matter of deep personal conviction.

There’s a division in environmental circles, I learned, between those who embrace “catastrophism” and those who reject it. Many mainstream environmentalists prefer to focus on hopeful progress, positive scenarios and the possibility of meaningful social change. Others, like most of those in the room that evening, assume a position of sombre realism: the situation is already bad, and it’s about to get much, much worse.

U.S. Congresswoman Alexandria Ocasio-Cortez acknowledged the burden climate change is placing on people of child-bearing age in a widely reported Instagram video earlier this year: “There’s scientific consensus that the lives of children are going to be very difficult. And it does lead young people to have a legitimate question: Is it OK to still have children?” Subscribers to a movement called #BirthStrike have decided it isn’t. In their declaration, they say their choice not to have children is “a radical acknowledgement that our planet has entered a 6th Mass Extinction event due to man made impacts on the environment.”

Also on Broadview: 6 acclaimed Canadian authors write letters from the heart to their grandkids

One morning, when the fetus had grown to the size of a butternut squash and was consuming a pint of amniotic fluid every day, my wife and I met our doula at a café. I was concerned I wouldn’t like her. But this birthing coach was smart and professional; she made us cry happy tears. Up until then, the physical part of giving birth had loomed ominously, but the doula offered us an alternate vision: she made it seem like there was a chance the baby’s arrival might actually feel, well, special.

Later that same day, I attended a meeting of the Quebec chapter of Extinction Rebellion, an international organization that promotes non-violent action to pressure governments to reduce carbon emissions to net zero by 2025. About 20 people gathered into a dimly lit café to listen to a talk on the ecological crisis and learn how to get involved in the group. On the wall, a large pink flag proclaimed, “Hope dies / Action starts.”

A college professor and activist named Simon Bertrand gave an hour-long rundown of the planetary situation. I felt my chest tighten with alarm as he described the consequences of the permafrost in the Arctic melting and quickly releasing vast amounts of stored greenhouse gases. About 6.2 million square kilometres will become a long-term source of carbon, and when that happens, it will be irreversible.

Bertrand also told us a bunch of other terrifying stuff: millions of people displaced by rising temperatures and sea levels; crops dying; oceans acidifying; feedback loops reinforcing other negative effects that could accelerate the consequences of climate change. After the talk, the organizers handed out a form asking us what we can offer the movement. “Are you willing to be arrested?” the form asked. It offered three choices: Yes, No and Maybe. I checked Maybe. That night, I told Jocelyn I wanted to go to more marches and protests. “Okay,” she said, rubbing her belly. “Me too.”

Swept along by tangled currents of joy and panic, I decided it was time to reach out to Dave Courchene — Nii Gaani Aki Inini (Leading Earth Man) — an Anishinabe elder and knowledge-keeper who founded the Turtle Lodge International Centre for Indigenous Education and Wellness at Sagkeeng First Nation, on the shores of Lake Winnipeg. I was introduced to him five years ago. Whenever I have an opportunity to write an article that touches on the environment, I usually ask to talk to Courchene because there’s nobody whose perspective I trust more.

“We will never change out of fear,” Courchene told me, when I mentioned my anxieties. Instead, he said, we need to start from a different position. That means going back to the beginning and teaching our children to align with the Earth; it will provide what we need to survive, he said. “The earth will never betray those that have a reciprocal love and respect for her.”

After talking to Courchene, I began to think about how to spend more time and energy directly loving nature. Activism and education are essential, but when I face the realities of climate change, I need to feel rooted in a positive expression of care. I’m still in the beginning stages of a transformation in my relationship to nature, which I feel is part of a collective re-rooting of our civilization. We won’t save the planet unless we love it.

This may sound pathetic and stupid, but I figured I’d prepare myself to become the parent I’ll need to be in these times by practising on our cat. I began to look at him differently — how he’d hug Jocelyn’s belly-bump like a shipwrecked sailor clinging to a buoy — reflecting on the extent to which the quality of his life depended directly on how we treated him, how we were the defining feature of his existence.

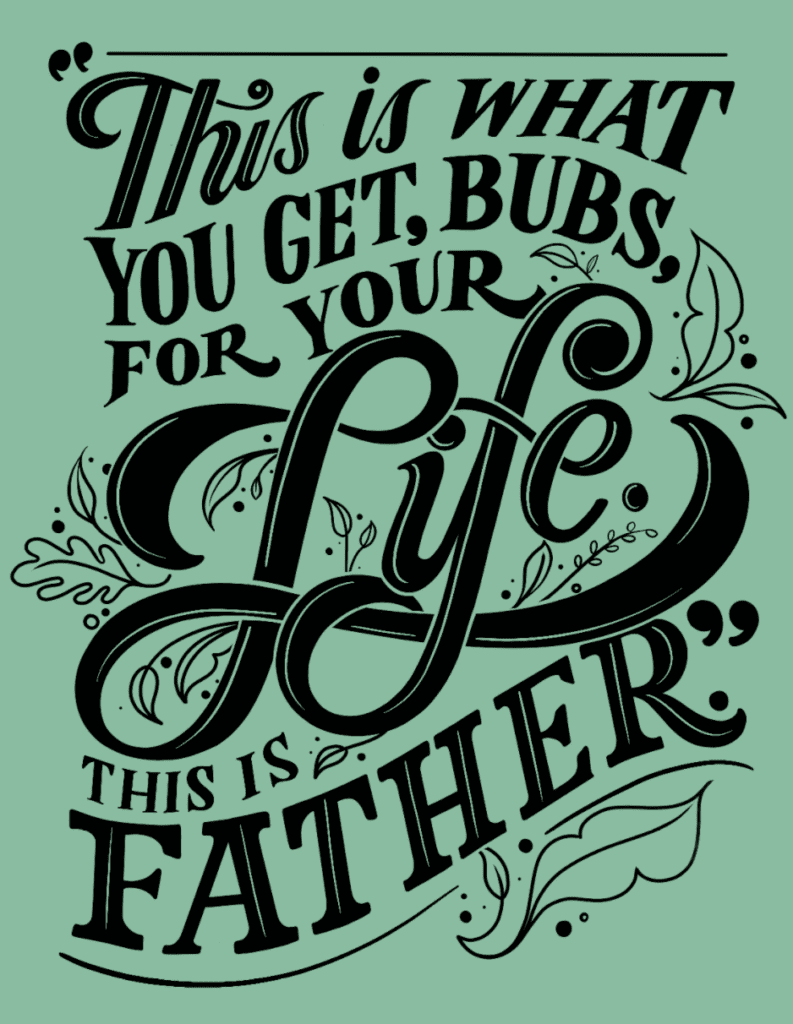

The thought was strangely exhilarating, and it led me to think about my child, who was by then barrelling toward birth, and also about our gorgeous, suffering biosphere. This is what you get, Bubs, for your life. This is father. This is mother. This is cat. There is sky. These are trees. Here is Earth. This is love. You’re okay. It’s good to be you. Take your time. Have fun. Be well.

“The earth will never betray those that have a reciprocal love and respect for her.”

Dave Courchene

Postscript: As I write this, my baby boy is still preparing to be born, in just over a month. Jocelyn can’t wait to have him out: he writhes in her stomach like a python and keeps her up at night with his calisthenics.

I’ve taken to telling people that if it weren’t a miracle, pregnancy and childbirth would be more like a horror movie. Even so, I daydream all day about playing with my son, and I watch other parents with jealousy, because they get to hang out with their kids.

Jocelyn and I stayed up late the other night talking about our planet’s desperate future. She’s scared, too, but she expects society to be forced to change in ways that are positive. Hopefully, our child will play a role in creating a more equitable world, where humans honour their dependence on Mother Nature. In the meantime, we just need to surround him with unshakable, unquenchable love.

And I finally did organize my prayer meeting, except I dropped the word “prayer.” I’m calling it “Sit for the Earth,” and it’s just a basic space — 30 minutes of silence, plus a few minutes of sharing — for people to perform the interior work we all need to do as we adapt to our changing planet. The first gathering is next week, and it looks like three or four people might come, which is fine.

This story first appeared in the June 2019 issue of Broadview with the title “Parenting in the Age of Climate Change.” For more of Broadview’s award-winning content, subscribe to the magazine today.

Mark Mann is a writer in Montreal.

If you stopped praying to a God, why were you praying? You theoretically just changed gods that’s all.

Funny, as a parent, the first child you pray: Let it live through its term; Let it be healthy; Let it be a girl/boy. By the third child you’re praying: What, another one; Do I need a bigger house; Do I need a better paying job.

Then later you are doing it all over again with Grandkids – tweaking the questions. Life is full of wonder.

When I read a story such as this (parents struggling for a child), I ponder the question: Why would anyone what to abort a fetus?

Children are a command, blessing and an heirloom from God. Gen 1:28, God blessed them and said to them, “Be fruitful and increase in number; fill the earth and subdue it. Rule over the fish in the sea and the birds in the sky and over every living creature that moves on the ground.” and Psalm 127:3 Children are a heritage from the Lord, offspring a reward from him. (Although I will admit, they don’t always feel like a blessing)

Finally, when I was born in the 50’s, many thought the big “bomb” was going to drop very soon. Mom always said “I was sure it would be the next day”. But here we are. Climate change theory is man saying: “We are in control of our life and destiny, not God”. Isaiah 46:10, I make known the end from the beginning, from ancient times, what is still to come. I say: My purpose will stand, and I will do all that I please.

We also have the great promise in Matthew 6:24, Therefore do not be anxious about tomorrow, for tomorrow will be anxious for itself. Sufficient for the day is its own trouble.

If you stopped praying to a God, why were you praying? You theoretically just changed gods that’s all.

Funny, as a parent, the first child you pray: Let it live through its term; Let it be healthy; Let it be a girl/boy. By the third child you’re praying: What, another one; Do I need a bigger house; Do I need a better paying job.

Then years later you are doing it all over again with Grandkids – tweaking the questions. Life is full of wonder.

Children are a command, blessing and an heirloom from God. Gen 1:28, God blessed them and said to them, “Be fruitful and increase in number; fill the earth and subdue it. Rule over the fish in the sea and the birds in the sky and over every living creature that moves on the ground.” and Psalm 127:3 Children are a heritage from the Lord, offspring a reward from him. (Although I will admit, they don’t always feel like a blessing)

Finally, when I was born in the 50’s, many thought the big “bomb” was going to drop very soon. Mom always said “I was sure it would be the next day”. But here we are. Climate change theory is man saying: “We are in control of our life and destiny, not God”. Isaiah 46:10, I make known the end from the beginning, from ancient times, what is still to come. I say: My purpose will stand, and I will do all that I please.

We also have the great promise in Matthew 6:24, Therefore do not be anxious about tomorrow, for tomorrow will be anxious for itself. Sufficient for the day is its own trouble.

Mark must mean June 2018……we’re only in May of 2019.

On another note, yes, this planet is having alot of difficulty but does the Bible not make plain that after Jesus return, He will re-make it…..new heavens and new earth, spoken of in both Old and New Testaments? So Christians are to be good stewards of their little part of the world, but also have faith and trust that God will look after His people. No need for panic. Thoughts?

Thank you for this beautiful and beautifully-written reflection on this moment in Earth’s life. You touch on so many important themes and remind us of vital facts with a gentle and heartwarming simplicity.

When coping with my own temptations to surrender to alarm, you remind us that each of us can only do our best to live loving and ethical lives. I believe your son is blessed to have you as parents, and will be a blessing for all of us.

I regret that the church did not see your initiative as an opportunity to grown in circles of mutually- affirming forms of faith, and celebrate that you have found a welcoming host.

Namaste.

This is a remarkable article and I’m so appreciative that Broadview has published it. Thanks to all, and especially to the expectant mother and father who have shared their intimate journey with us. Thank you very much.

– A thankful great grandfather – Dale Perkins (whose youngest daughter told me she has decided not to have a child. So attempting to accommodate that knowledge into my spiritual life.)

I am deeply moved by Mark Mann’s entire piece, but his conclusion brought a joyful smile to my face! Not only do I applaud his extensive research and relentless, exact, tender recording of his experience of impending parenthood in a world that seems to be ignoring the cries of the earth, but I fiercely embrace the reason for hope in the end. From the wisdom of a First Nation’s scholar, Leading Earth Man, we hear, “not fear, but love” will strengthen us in the Way. Love the earth I have done since my earliest days, and yet I am heart-sick about what is happening, and fear for the future safety and well-being of my children and grandchildren. Thank you, Mark and Leading Earth Man, and Broadview for restoring my vision.