Homelessness has surged in recent years, aggravated by the COVID-19 pandemic. In Toronto’s Kensington Market, St. Stephen-in-the-Fields Anglican Church became host to an encampment in 2022, when a community began to form in the yard beside the church.

For Mother Maggie Helwig and her parish, the encampment allowed its residents to survive and support each other. For others, it was a problem to be solved.

You may unsubscribe from any of our newsletters at any time.

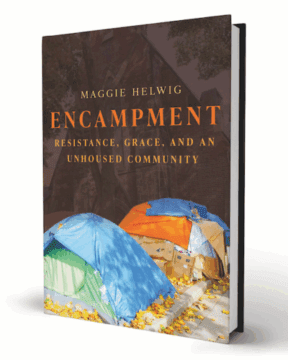

Encampment: Resistance, Grace, and an Unhoused Community is Helwig’s story of caring for the residents and defending the encampment from the legal and political forces that sought to dismantle it.

Today, the churchyard has only two remaining permanent residents, as well as two others who come and go frequently. After the city removed the residents’ belongings and placed a large fence around the churchyard in fall 2023, most relocated to encampments elsewhere. But the church continues to be a site of community and connection for former residents and others experiencing homelessness.

Amarah Hasham-Steele spoke with Helwig about Encampment and the events that informed it.

AMARAH HASHAM-STEELE: In addition to being a priest, you’re also a novelist and poet. How did you approach writing a non-fiction book?

MAGGIE HELWIG: I’ve been given access to this world of encamped people, and that put me in a position to communicate some of the realities of that world. I should note that I spoke to the people in the encampment who are primarily featured. They were aware they would appear in the book, and they gave me direction on whether they wanted to use their real names or other things to include. They gave me permission to write as I saw fit, for the most part.

AHS: One of your tasks as pastor was responding to neighbourhood complaints about the encampment. You write, “My answers came from the land of affliction, and the land of the well seemed unable to hear me.” Can you elaborate on this?

MH: I don’t want to be overly critical of the people who were hostile to the encampment, or who continue to be hostile to overdose prevention sites or supportive housing. I think people often have a great deal of privilege of which they are unaware. Not just economic and racial privilege, but the privileges of being reasonably able-bodied, reasonably neurotypical, fitting in with society without too much friction, or able to operate in our current matrix of late capitalism without a lot of suffering.

Illness, suffering, difference — all of these things are frightening if you haven’t lived in that world, and people will go to tremendous lengths to block themselves off from things that frighten them. They have a really hard time telling the difference between what is frightening and what is actually dangerous.

AHS: What do you want people to take away from the book?

MH: There are encampments everywhere now — in Canada, in the States. Most people walk by them and think, “This looks like a horrible, terrifying place.” And if the book can play any role in making them think differently, that’s what I would like to achieve. To help people look again and say, “I see how people in here are supporting each other and building a community and actually creating something in a very difficult situation.”

AHS: Why did you choose to include homilies from holiday services in Encampment?

MH: I have tried not to make the book particularly religious. But the way that my parish responded to the encampment reflects a profound theology of the incarnation. To say that God became flesh means that God is here with us, encamped.

In one of the homilies, when John says, “The Word became flesh and dwelt among us,” the actual Greek word means, “the Word became flesh and pitched a tent among us.” The themes of exile and displacement echo through scripture. God is with the displaced and the suffering.

Many people also supported the encampment from other perspectives. We have a church community that includes atheists and practising Jews. But for the part of the community that goes to church, there was very much a theological impulse behind our response to the encampment.

More on Broadview:

- Tent cities are growing in Canada — so is the call for meaningful change

- Community support helps refugee family find home amidst Canada’s housing crisis

- Uncertainty clouds future of tiny cabins for Kingston’s unhoused

AHS: What role does hope play in your story?

MH: I’m not sure it does play a significant role. Hope requires an orientation toward an imaginary better future. If people cannot imagine a better future, that’s not a failing on their part. Many of us, in our different ways, are focused on survival, on building community — things that are positive, but the word “hope” doesn’t enter into it much.

I’m critical of people calling for hope or talking too much about hope in troubling times. I don’t think it’s a good motivator. I think it will let us down.

AHS: If not hope, is there a word you would use to describe the book’s emotional undercurrent?

MH: Community. It’s a story about community.

***

This interview has been edited for length and clarity.

This article first appeared in Broadview’s July/August 2025 issue with the title “Tent Sanctuary.”

Helwig captures (sometimes beautifully) the day to day brutal grind that is to be unhoused. Her observation that ‘answers’ to the unhoused crisis (and there are answers) seem not able to be heard is as honest an assessment as it is poignant. The sad fact is we know how to solve the unhoused crisis. Politicians have the reports, the best practice models, the Scandinavian examples for eliminating the crisis. Yet, we choose not to. This is not just about ignorance. It is a willful indifference. An aspect of our culture – and I would argue it is an “Old Testament” attitude – that prefers a desire for punishment over resurrection.