In late September, Canada entered the small but worrying club of countries with extremely low fertility, joining South Korea, Spain, Italy and Japan in the so-called “lowest low,” with a national average of 1.26 children per woman according to Statistics Canada. Just a few weeks earlier, Parliament voted down Bill C-223, which aimed to create a national framework for a Basic Income. While Universal Basic Income (UBI) is often cited as a cure for deep poverty, research shows that it could also be a solution for many social ills — among them, the declining birth rate.

Low fertility, without high levels of immigration, has major consequences for a country: it shrinks the economy, generates less tax income for social programs and reduces the number of caretakers and other workers who keep society running. Without a solution, we could face economic depression, stagflation and an unraveling of our social fabric.

You may unsubscribe from any of our newsletters at any time.

So, how would it work? Most people want more kids, according to a 2023 Gallup poll. The reason why they aren’t having them is that they can’t afford it. Kids are really expensive: A middle-income family with two parents and two kids spends $17,235 per year on each child. That adds up to an average of $293,000 to raise one kid until the age of 17, according to 2023 data by Statistics Canada.

Handing out $17,235 per year to families obviously isn’t going to happen, but interestingly, the data shows that you don’t actually have to give people that much money for them to start thinking about storks and diapers.

Consider one of the longest running successful UBI programs in Alaska, called Alaska’s Permanent Fund Dividend. Funded by oil dollars, the state of Alaska has been giving every woman, man and child an annual chunk of its nest egg since 1982. The exact amount varies each year based on the oil market, inflation, stock market and a few other factors, but it works out about between $1,000–$2,000 per year per person—or roughly the cost of daycare for about one month.

The amount may not seem like a lot, but Alaskan birth rates have risen nevertheless. According to a 2020 National Bureau of Economic Research working paper, fertility in Alaska sharply increased by 13 percent for women between 15 and 44 years of age since the introduction of the UBI payments.

A similar payout could help Canada raise its extremely low birth rates, says Floyd Marinescu, founder of UBI Works, a non-profit devoted to making basic income a reality for all Canadians. As an example, he points to the Manitoba Basic Income Experiment, or Mincome for short. The UBI experiment, which took place in the town of Dauphin, Manitoba from 1974-1979, was one of the largest in the world. It gave any participating household $4,800 in 1975, or just over $25,000 in today’s money.

The results showed that poverty wasn’t just about how much people spent on consumer goods; it was about health outcomes and wellbeing. UBI changed how people ate (more fruits and veggies), how much time they spent on education, whether they got dental care and how they were able to care for their mental and physical health. In other words, it helped create optimal conditions for parents to raise children.

More on Broadview:

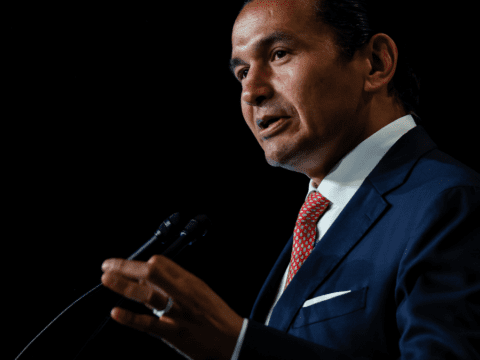

Marinescu, who grew up in Toronto, says a program like this would have changed his upbringing. As a child, his mother worked as a cleaner, and his dad was in auto manufacturing, but they lived paycheque to paycheque, and his parents would often fight about money.

Today, he runs a successful tech education business, which has allowed him to bankroll the UBI Works. The non-profit has drummed up support from business leaders, politicians, activists and others to turn it into a movement. They also funded a 2020 report run by the Canadian Centre for Economic Analysis that showed basic income could grow Canada’s economy $80 billion per year and create as many as 600,000 jobs.

“We need to convince politicians that there’s enough public support for this,” Marinescu said.

Other studies have found similar benefits UBI has on the economy, but whether you agree with them depends on how you think about economic growth. In short, if you subscribe to Keynesian or neo-Keynesian economics — a theory that highlights the power of government spending to boost demand and spur growth — you’ll recognize the enormous potential in those free-money cheques. If you are a fiscal conservative, you’ll probably dismiss them as being too expensive.

One of the problems with UBI, and the difficulty that it has with gaining political traction, is that funding the scientific experiments to prove, beyond a reasonable doubt, that it would be good for the economy is expensive. Consider the 2017 trial in the town of Lindsay, Ont., population approximately 22,000. Those living in Lindsay, such as town councillor Mike Perry, who helped bring the experiment to the town, fully expected that since most of the money was being spent on consumer goods inside the town, it wouldn’t just increase physical and mental wellbeing, it would have a stimulus effect on economy. But no one will ever know because the three-year trial was canceled by the Ford government after just one year.

The federal government has had its share of defeats, too. Three years before Bill C-223 failed, Liberal delegates overwhelmingly endorsed a resolution calling for the establishment of a universal basic income in Canada, which went nowhere.

Despite these setbacks, Marinescu remains optimistic that UBI could be the gateway to a more just and sustainable future. Think about what lies ahead: for the bottom 50 percent, the future looks increasingly unfair. Several studies predict rising unemployment due to AI automation, widening income inequality from technological advancements and worsening food insecurity driven by climate change. For the poor, simply getting by, let alone raising children, will likely become a struggle. The Silicon Valley version of the future may not be what we need or can stomach. Marinescu wants your consideration.

***

Alexandra Shimo is a writer and journalist in Toronto.