It’s the first night of Passover in the early spring of 2022. My husband, Dan Zimerman, and our adult children, Rachel and Sam, are gathered around our dining room table along with my mom, Agnes Moskot. In the centre of the table is our seder plate, the matzah wrapped in a silvery woven cloth, and a small bowl of salty water for dipping our parsley.

On the sideboard, just out of the corner of my eye, I can see a familiar envelope. My mom brought it to our home in Montclair, N.J., with the sole purpose of giving it to me just as her mother had given it to her. I had no idea this was her plan, but I know full well the chilling, yet holiday-appropriate, content that lies within it.

You may unsubscribe from any of our newsletters at any time.

We each read from our wine-stained Passover Haggadah, retelling the biblical story of the Exodus — a turning point for us as a people. We were slaves for 400 years before God rescued us as chosen people and called us to be in our own land. As Jews, we are commanded to tell the story of how we fled slavery at the hands of the Egyptians so that future generations will remember.

I’d heard this story every Passover since I was a child growing up in Toronto, where my mom still lives; I know that, for our family, slavery is not a thing of the biblical past. Our history lies within that protective plastic envelope on my sideboard, in the form of five postcards. Although I am not exactly sure what they say, their existence has captivated me for my entire life, especially on this holiday.

You see, Passover is also close to Israel’s Holocaust Remembrance Day or Yom HaShoah, both falling within two weeks of each other in April this year. Jewish people observe Yom HaShoah to commemorate the approximately six million Jews and others murdered by Nazi Germany and its collaborators, and the heroism of the survivors and rescuers. The two holidays are intertwined with one another and with my life.

After the blessings over the first cup of wine and after we explain the symbolism of each element on the seder plate, we soon reach that familiar passage: “We were slaves to Pharaoh in Egypt…” As Dan begins to recite the story of our enslaved forebears, my thoughts drift to a more recent story of slavery and one person in particular, my maternal grandfather, László Braun.

Almost 80 years ago, in 1943, the Nazis made him a slave when they sent him to the copper mines of Bor, Serbia. He never returned. For Elizabeth, his wife and my grandmother, the trauma of losing her beloved László drove a permanent wedge into her heart. Although I would sometimes see a smile on those Revlon red lips, it always quickly faded. It pained me that my mom, Agnes, affectionately known as Ágika, had never met her father.

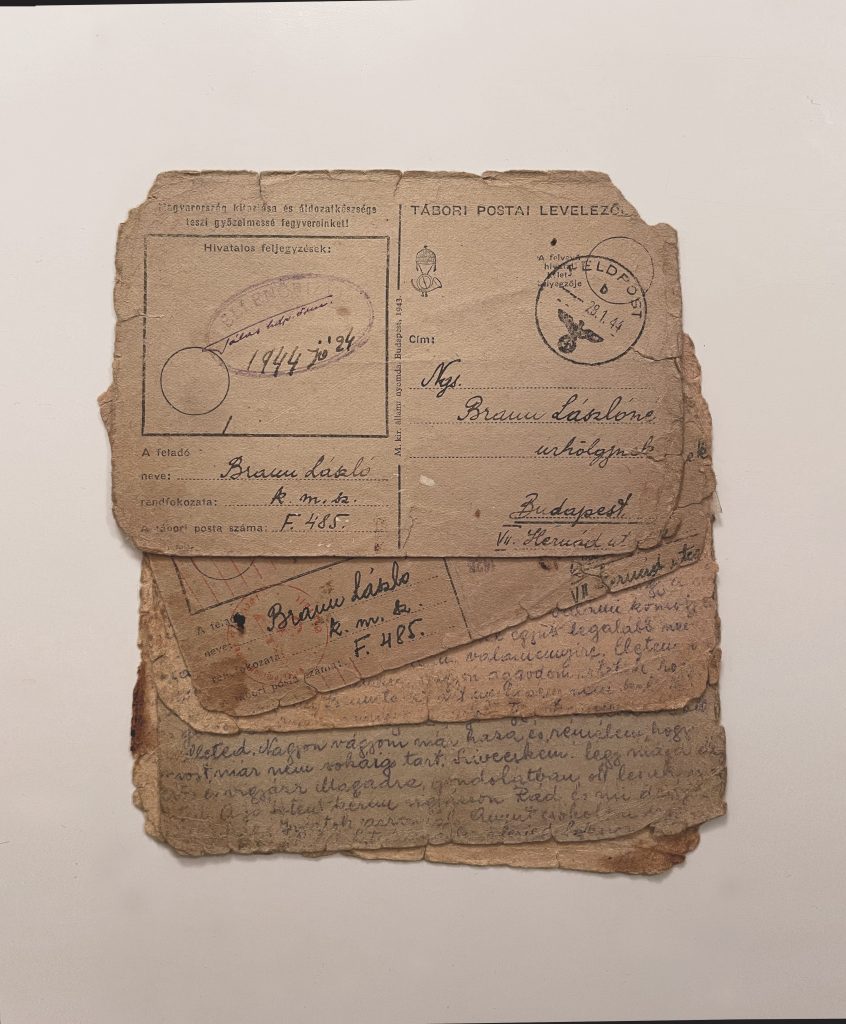

At the conclusion of the seder, my mother presses the envelope into my hands. It contains the last letters Elizabeth received from László — five fragile brown postcards filled with faded black ink, their edges frayed with time. I get shivers of dread at the sight of them, conscious of the responsibility that is being transferred to me. I see it as my duty to preserve the memory of our family members who were murdered. What I don’t realize at this moment, though, is that this gift will introduce me to the grandfather I’ve never known, revealing the warmth and love within a marriage cut short.

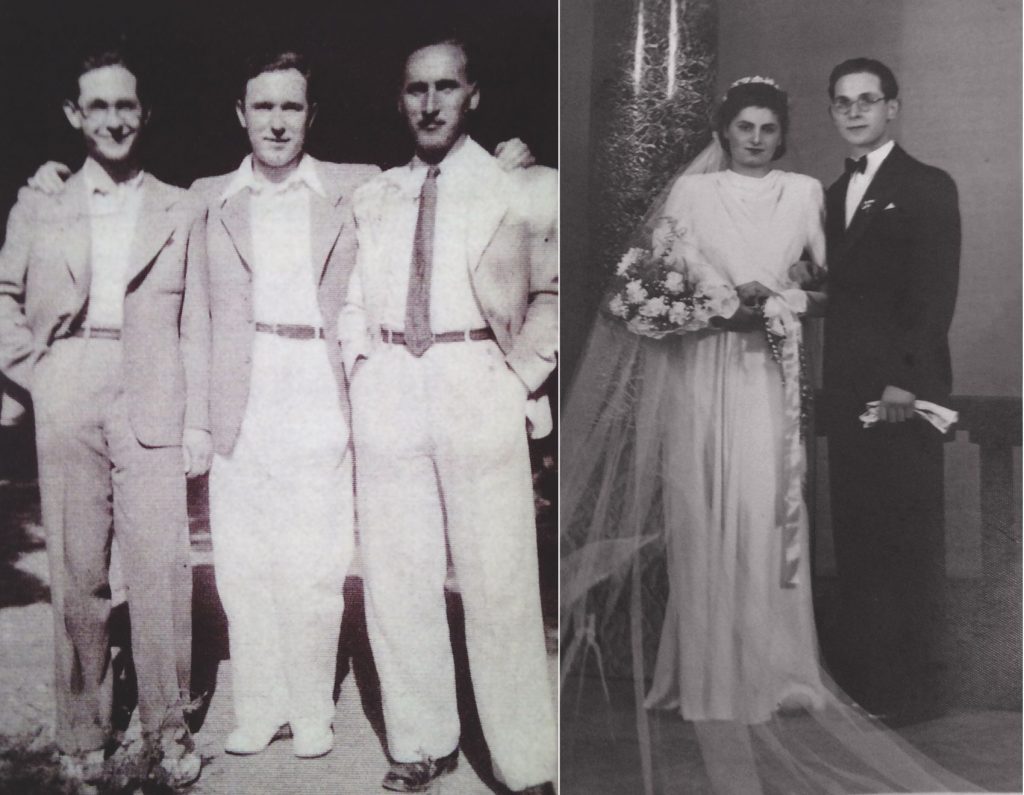

My grandmother, Elizabeth, rarely spoke about my grandfather. The only two photos of him hung on the wall of my mother’s apartment. In them, László was frozen in time — forever smiling. The fact that these images even exist is a miracle. Elizabeth protected them during the most brutal years of the Second World War and hid them during the 50-day siege of Budapest that began in December 1944. That was when the invading Soviet army, together with Romanian forces, sought to overrun the Nazis and destroyed most of the city.

The first photo, taken sometime between 1939 and 1941, is of a baby-faced, bespectacled László together with his brothers, my great uncles, Zoltán and Béla. All three Braun boys were brutally murdered during the last year of the war. Slight, with pale skin and black hair swept back to reveal big smiling eyes, László was a talented furniture designer and upholsterer. As the youngest, he was expected to stay in Budapest and take care of his widowed mom, Sára Márványkövi. Zoltán, the middle brother, left home to study architecture at the Sorbonne in Paris, returned and married the gorgeous Veronika Szilágyi. Béla, the eldest, married Magdolna Schwarz and had a baby son.

The second photo is a formal wedding portrait of my grandparents. László, 25, is in a tuxedo and stands next to my 22-year-old grandmother. Elizabeth Grün is wearing a dress that only a few years prior her sister-in-law Veronika had worn for her own wedding.

When Elizabeth was in her late 70s, I mustered up the courage to ask her how she and László met and what he was like. I didn’t want to bring up painful memories, but I wanted to learn about my grandfather, her one true love. Elizabeth grew up in the 7th district of Budapest, the city’s historic Jewish quarter. She and László met at a dance put on by the Jewish Women’s Club at the Bethlen Square Synagogue where they were both members. She explained that they got to know one another when they attended high holiday services and went for a walk on Yom Kippur. “That is when people walk,” she told me. “We first went to synagogue, and then some of us youngsters went for a walk so that time passed.”

When I asked what László was like, she flashed that rare grin. “He was a really nice guy, he wore glasses. He was a very handsome, good boy.” They were married on March 16, 1942, in the synagogue where they first danced together. Then our conversation quickly shifted and darkened. “But unfortunately, there came the war. That is why we could only live together for one and a half years.”

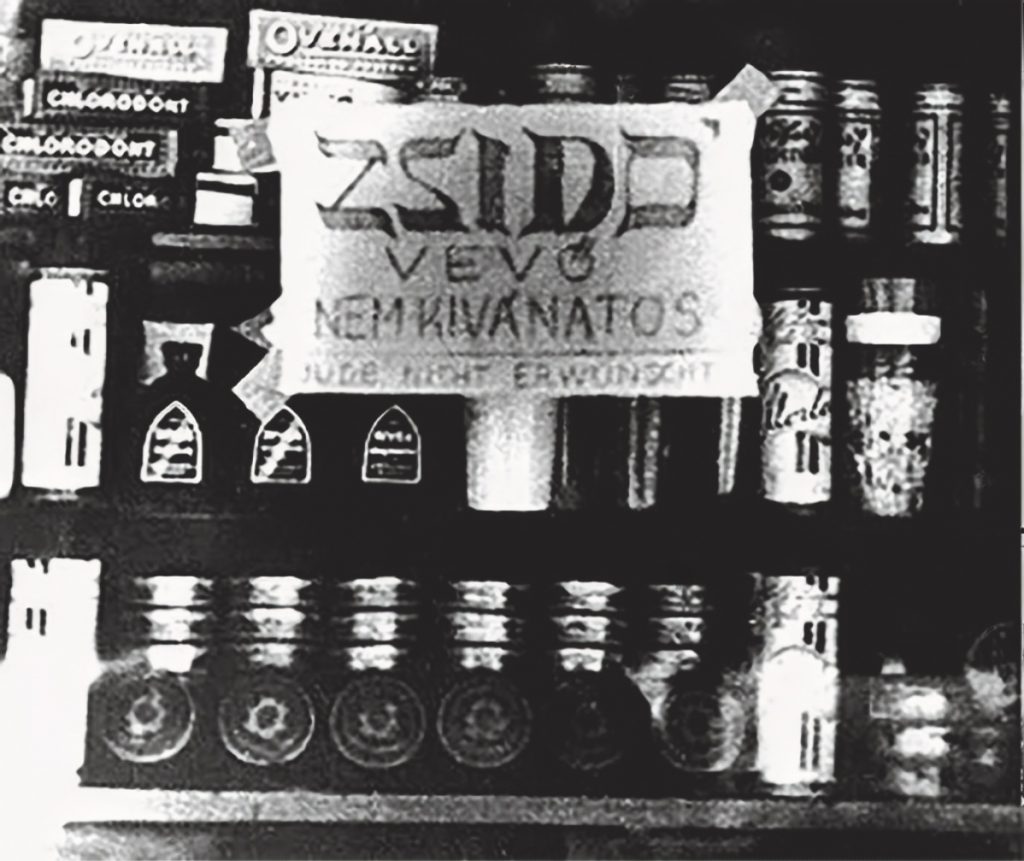

Hungary has a long history of antisemitism, dating back before the Second World War. The 19th and early 20th centuries were an era of transformation as the country moved from a feudal system to a capitalist economy. While many benefited from this shift, others were on the losing end. As is so frequently the case, frustrations were taken out on Hungary’s Jews, including hundreds of pogroms (violent attacks and massacres), often carried out by citizens.

In 1920, 13 years before the Nazis rose to power in Germany, the newly elected right-wing Hungarian government established by autocrat Miklós Horthy passed one of Europe’s first anti-Jewish laws. The Numerus Clausus Act limited Jewish enrolment in higher education (hence László’s brother Zoltán going to Paris for his education) and effectively quashed the legal equality of Jews in Hungary. The government continued to add more restrictive laws, including preventing Jews from owning property and participating in public and cultural life.

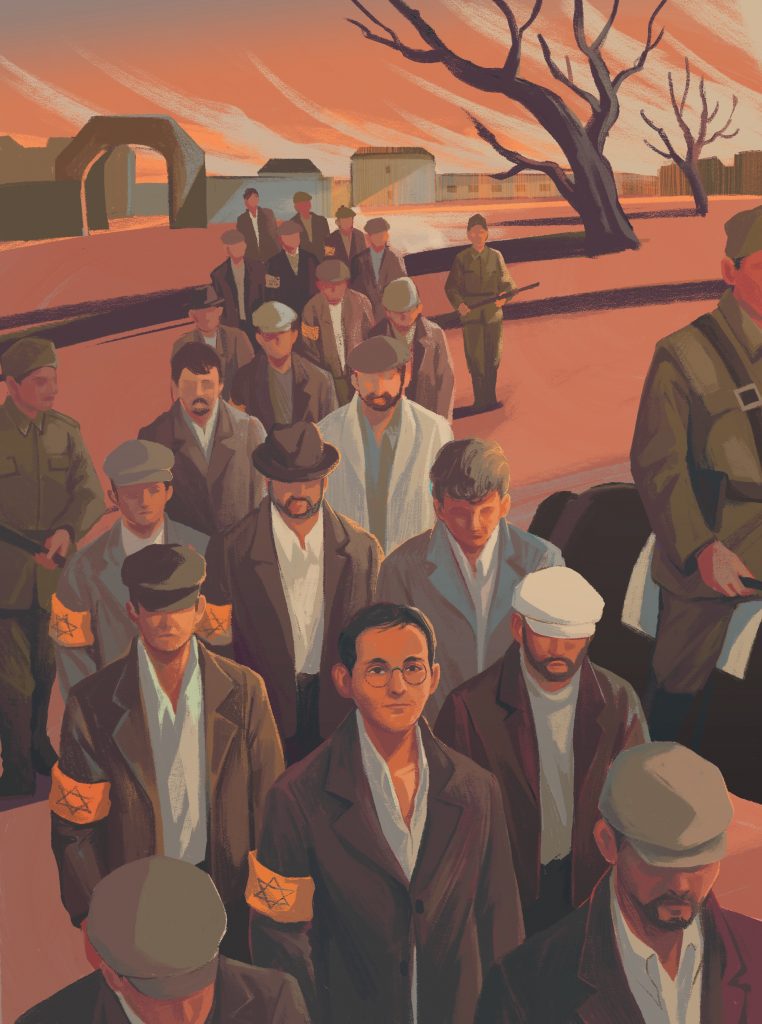

In 1940, Hungary allied with Germany. When Nazi forces invaded the Soviet Union the following year, Hitler eventually demanded that Hungary mobilize its military. For almost a century, Jews had proudly served in the Hungarian armed forces, including my great-great grandfather. But during the Second World War, Jewish officers were discharged because they were Jews. The Hungarian military created a new forced labour system that required Jewish males to serve at least two years. Deemed “unsuitable” to carry a rifle or wear a uniform, the men laboured in civilian clothing and wore yellow arm bands, making them open targets for both Hungarian and German antisemites.

Following France’s defeat in 1940, Europe’s largest copper mine in Bor, Serbia, was transferred from French ownership to the Germans. Nazi civilians operated the mine and used Jewish slave labour. Bor was an important source of copper for the Reich’s war industry to make cannonballs, cartridges, machine guns and tanks. The problem was that by 1942, the entire Jewish population of occupied Serbia had fled or been killed, so the Nazis turned to the remaining Jews of Hungary to supply that labour.

In 1943, the Hungarian government bowed to Germany’s pressure and sent three groups of mostly Jewish forced labourers to the Bor mines. On July 25 of that year, my grandfather received his call-up to Bor. Notices were delivered in person and had to be signed. László would have had a day or so to prepare. Newlyweds for just over a year, he and my grandmother, Elizabeth, said their goodbyes. He promised her he would return as soon as possible.

After Passover, my grandfather’s postcards sat on my desk for weeks before I got the courage to have them translated. My mother had read me snippets, but never a full card. I wanted to hire a professional translator so I could glean subtle details and gain some insight into the person my grandfather was. But part of me was terrified of the pain that was headed my way. I knew how László’s story ended. Would I feel his loss that much more?

My Budapest-based translator, Bence Kovacs, took approximately three hours to translate the postcards to English. In his email to me, he said, “I hope you will like them, however tragic it is indeed.” I had no idea what I would encounter or how I would feel as I settled in to read them, one by one.

POSTCARD 1

Dated Nov. 7, 1943, and stamped by Sgt. Talas

Mailed Nov. 9, 1943, by Nazi Feldpost

Sender’s Name: László Braun

Rank: Auxiliary Forced Labourer

Field Post Office Number: F 485

Sent to: Mrs. Lászlóné Braun

14 Hernád utca, District 7

Budapest

My Little Darling,

You must have been very worried that you haven’t received a card for a long time, but it was impossible to write, unfortunately. Thanks God, I am well…I’m not lying. I received the package a long time ago, I was very happy about it. It serves me well, because it is quite cold already. But that you want to send me my beige suit, I am not so pleased about it, because I do not need it. The pants I got from OMZSA [National Hungarian Jewish Aid Organization] I do not wear, but I will take it home, it will make a nice costume for you. My love! I always get your letters, keep writing to me, because I have not received anything this week. I am very happy that you are well, you are about to go to the hospital soon. I am very worried, you can imagine, it hurts so much that I cannot be with you…I am longing for home a lot, I hope this won’t last long. My darling! Be strong, and take care of yourself, my thoughts are wandering around you, I am asking the Almighty to look out for you and our little darling. Please write…I am sending my kisses to Mom as well.

Your husband,

Laci

I ran my eyes over the words written across the first postcard several times, absorbing László’s endearments, his longing for home and family, how he signed with his pet name. I felt as if I was meeting him for the first time. I took in his kindness, his concern and his affection. His thoughts were of his mom and Elizabeth, who was four months pregnant with my mother when they parted in Budapest. Each sentence begged another question. Why was it impossible to write? What was his day-to-day world like as a slave labourer? What kind of work was he doing? I felt an urgency to piece together a more fully formed picture of what happened to László at Bor — exactly what was hiding behind the carefully worded postcards?

To fully understand László’s experience as a civilian in the forced labour complex in Serbia, I read Ferenc Andai’s memoir, In the Hour of Fate and Danger. Andai was 19 and living with his mother in Budapest when he was called up for labour service in Bor. His first-person account described in detail the difficult work the men carried out, along with the severe deprivation they endured. He also describes the friendships and the necessity of trying to maintain a degree of normalcy while in this situation.

A shiver ran through me as Andai recalled one of his bunkmates telling biblical stories about Jewish slave labourers building the ancient Egyptian cities of Pithom and Ramses, being exploited and tormented and how they were miraculously set free. I knew there was no miracle coming to save the Jewish slave labourers of Bor.

Andai explained that travel to Bor took five stench-filled, oppressive days by train, starting in Vac, Hungary. Andai’s cattle car was crowded with 40 men. The train pushed through some of the most remote and beautiful forested landscapes of the Serbian mountains. The men arrived at a complex of 33 sub-camps ironically named after cities of the Third Reich.

Jewish slave labourers received three meals a day of thin soup and mouldy bread. They worked 10- to 12-hour shifts. Some repaired roads or built the Bor-Žagubica railway, but many worked in the mines, often standing knee-deep in water and breathing in dust and explosive gas. This work was always accompanied by death threats and antisemitic harassment by the Nazis who oversaw them.

By the time my grandfather arrived, he would have encountered Lt.-Col. Ede Maranyi, commander of the camp, along with a brutal regime of officers and subordinates who were encouraged to commit atrocities. They punished the labourers for alleged offences with beatings, trussing up and hog-tying.

I studied the date of Dec. 30, 1943, on the second postcard and realized László had become a father. Two months before, Ágika was born prematurely at seven months in a maternity hospital. She weighed 2.2 kilograms (less than five pounds). She and my grandmother stayed in the hospital for two weeks before going home to their apartment. László was hundreds of miles away, forbidden by the Nazis to take a short leave and see his newborn daughter and wife.

László wrote: “I have received your letters written until 15 December, I am very happy that you’re fine and our Ágika is growing well. I cannot express how much I want to see her. You always tell me…how beautiful she is and I still have not seen her, you know how annoying that is. I have received her birth record, but unfortunately, I do not need it, I cannot go on leave yet…It is Christmas Day today, and our little daughter is two months old, and I have to be here…this is so terrible that I want to cry. Exactly one year ago how happy we were…The only thing that keeps me alive is that I will get home one day, and then we will be so happy as no one has ever before, I dream about this all the time.”

László’s third postcard was written on Jan. 24, 1944. My grandfather was clearly trying to mitigate Elizabeth’s fears for his safety, writing to her: “Thanks God, I am fine, you do not have to worry about me. The weather feels like spring, one can walk around in a spring overcoat. If only it stayed this way until we get home, soon, I hope.”

He went on to imagine what life would be like when he returned, and asked after his brother Zoltán, who was held in a slave labour camp somewhere near the border between Ukraine and Hungary. “It is Sunday today and the weather is nice, it almost breaks my heart how much I am longing for home. How great would it be now in the City Park, walking just the three of us, which may happen sometime as well. How is Mom? I am sending many kisses to her. Any news about Zoli?”

The card ends with, “Please kiss our dear little Ágika for me, as she has just turned three months old. I am sending you my kisses. Your loving husband, Laci.”

As I read through the third postcard, I quickly began to piece together what was taking place in Budapest at that time. László would have been devastated had he known the immense danger his beloved Elizabeth faced, along with thousands of Jews in the city. In one of the few times I asked Elizabeth about this time in her life, she told me she had been extremely worried: “I was on my own [with a baby], and I had no support. I worked from home, sewing, and that is how we could make ends meet.”

During the war, Hungary was in the crosshairs of both Germany and Russia. On March 19, 1944, the Nazis took control of Hungary to prevent the country from negotiating a truce with the western allies. The Russians meanwhile advanced on the eastern front. Despite discriminatory legislation and widespread antisemitism, the Jewish community in Budapest was relatively secure until German occupation. The Nazis ordered the establishment of a Jewish Council, a group of Jewish leaders charged with relaying orders to the Jews, and severely restricted Jewish life.

All Jews were soon required to wear the yellow star. Jews living outside of Budapest were rounded up and forced to live in designated ghettos and camps in more than 200 locations. Police guarded the perimeters, preventing anyone from leaving, and they often extorted Jews. Food and water were in scant supply, and no one had access to medical care.

In May, SS Lt.-Col. Adolf Eichmann, chief of the Nazi team of “deportation experts,” worked with the Hungarian authorities to start deporting Jews. In less than two months, nearly 440,000 Jews were forced from Hungary in more than 145 trains that took most of them to the concentration camp Auschwitz-Birkenau, in Nazi-occupied Poland.

By mid-1944, about 25,000 Jews from the city of Budapest had been rounded up and transported to Auschwitz, including my great-uncle Béla, his wife, Magdolna, and their two-year-old son. Upon arrival, all three would have been sent directly to the gas chambers. Hungarian authorities suspended the deportations in July 1944, sparing, for the moment, the approximately 280,000 Jews still in the capital city. They were virtually the only ones left in Hungary.

Elizabeth was among those who remained. But she and Ágika had been forcibly moved from their home because of the antisemitic policies. The Arrow Cross, the Hungarian fascists, had confiscated apartments occupied by Jews, along with their belongings. About 170,000 Jews in Budapest, including Elizabeth, Ágika and Elizabeth’s mother, Teréz Kister, were herded into a handful of designated apartment blocks. Scattered throughout the city, these buildings were known as “the yellow-star houses” because they were marked with yellow Stars of David.

Elizabeth had heard the Swedish government, led by the diplomat Raoul Wallenberg, was helping Jews by issuing letters of protection, called a Schutzpass. She wrote to the Swedish embassy in fall 1944, explaining how she, her mother and baby daughter were living together in one small room. She had no job. She had no money to buy food. Could they help her?

Several days later, she had her own Schutzpass, which was typed on diplomatic letterhead, emblazoned with the Swedish coat of arms. It protected her and Ágika from immediate deportation to Auschwitz or other camps since the pass effectively made them wards of Sweden. Each month, the Swedish embassy also issued her a cheque for 250 pengo — enough to buy food for all three. That letter saved them many times from the fascist soldiers who roamed the streets of Budapest, often shooting Jews on sight or dragging them off for deportation. When Elizabeth showed her pass, they would harass her but let her return home.

Postcard number four, dated July 6, 1944, was mailed to the yellow-star apartment where Elizabeth, her mother and little Ágika lived with several other families. It is half the length of the other cards, written with a courteous formality and addressed to a Mrs. Blau, who would have been the head of the household.

László clearly spelled out his fears for his wife, whom he called by her pet name, Bözsi: “I would like to inform you that we are all well, thanks God. I am healthy, but I am very worried. I hope that you are fine, too. I am receiving the letters from Bözsi with much delay, I hope nothing bad has happened to her…I’m hoping that you will get this letter, because I know that you have not received any letter from me in the past three months.”

My heart fluttered with relief when he mentioned, “I have received the picture of our Ágika, I was very happy, but please send me more attached to your next letter.” László could finally gaze at the daughter he could not — would not — ever meet. He signs off, “I am sending my kisses to my Bözsike, please kiss Ágika in my name, I’m sending a million kisses to everybody.” I closed my eyes and imagined receiving one of those kisses myself.

I looked at postcard number five with dread. This was the last one Elizabeth would receive from László. I read it slowly, taking in the weight of his words as he tried to assure Elizabeth he was okay. Only he wasn’t.

They both understood their communication would be read by officers to ensure they were free of details that revealed the truth of what was truly happening in each of their worlds. What they received were sanitized versions. Each must have been terrified they might never see the other again. László knew the Nazis had finally arrived in Budapest. Elizabeth, Ágika and his family were in terrible danger, and there was nothing he could do to help.

The postcard was dated Aug. 14, 1944. By this time, the Soviet Army was swiftly closing in on Hungary from the east. The Nazis began to panic and ordered the Hungarian army to evacuate the Bor camp complex in two stages.

On Sept. 17, which was the eve of Rosh Hashanah, the Jewish New Year, the first group of about 3,200 forced labourers began the roughly 460-kilometre march to the Hungarian border under the supervision of 100 or so guards. They were each given only one kilogram of bread at the outset of their journey, marching 30 to 40 kilometres per day. The second group started to march on Sept. 29. All of these men had spent the last 14 months working in mines, quarries and construction sites, weakened by starvation and subjected to violence and torture. This was to be a death march. Men who collapsed from exhaustion were beaten or shot, as were those caught trying to flee or gather food along the road.

László was part of the first group of marchers. On Oct. 6, 1944, he was among 3,000 prisoners who arrived in Crvenka, Serbia, and were locked into a brick factory. SS men replaced the Hungarian guards. Beginning at around 11 p.m. the next day, the SS ordered the prisoners into rows of five and confiscated any remaining valuables. In groups of 20 or 30, the men were then marched beside a large trench and shot, one group after another, until at least 700 men had been murdered. The SS soldiers fired into the trench and tossed in hand grenades to make sure no one was left alive.

Between 3 and 4 a.m., the shooting suddenly stopped. The local German authorities had gotten word that Soviet forces were approaching, and the Germans were to evacuate Crvenka. László and the remaining prisoners were released from the factory only to be forced to march northwest, toward the Serbian town of Sombor. Along the way, at least 100 prisoners were shot on the side of the road after collapsing or stepping out of line, including László.

I searched the area between Crvenka and Sombor on Google Maps, looking at photos of rutted tree-lined roads surrounded by pastoral fields and forests. The images were sunless, bleak and eerily quiet. I imagined László being shot and left on the side of the road as the others kept marching. Did someone from a nearby farm bury him? What happened to the bodies of all those men who were murdered?

Among the prisoners in the Hungarian forced labour battalion at Bor was the celebrated poet Miklós Radnóti. Whether as a survival tactic or out of belief, he was a convert to Catholicism, but he still received his draft notice in May 1944. Radnóti wrote poetry about his experiences in captivity. He also wrote cards to his wife, Fanni. His last letter was dated Aug. 16 and included the words: “Thank you, my Dear, the nine years spent together…”

Like László, he survived the massacre at Crvenka but was later shot when he too collapsed on the march sometime in early November. He was 35. Radnóti was buried in a mass grave near a town not far from Gyor, Hungary. His body was later found with a notebook full of his poems written on the death march. His last poem was dated Oct. 31, 1944:

RAZGLEDNICA (Postcard) 4

I toppled beside him — his body already taut,

tight as a string just before it snaps,

shot in the back of the head.

“This is how you’ll end too; just lie quietly here,”

I whispered to myself, patience blossoming from dread.

“Der springt noch auf,” the voice above me jeered;

I could only dimly hear

through the congealing blood slowly sealing my ear.

On Oct. 16, 1944, the Nazis installed the fascist leader of the Arrow Cross, Ferenc Szálasi, as Hungary’s prime minister. In late November, 70,000 of the remaining Jews of Budapest were forced to march into a walled ghetto that was less than a square kilometre in size. The elegant Dohány Synagogue was on its western border. Elizabeth told me that when she walked into the ghetto with her mother and Ágika, “I [had] nothing. Just one dress, no food, no nothing.” Each day they would receive an eight-ounce can of soup. It wasn’t enough food to sustain one person, let alone a 13-month-old baby.

Life was full of violence perpetrated by the Hungarian Arrow Cross. No food was allowed in. Jews were shot at random. The dead lay in the streets. During December 1944 and January 1945, the Arrow Cross violence toward Jews escalated. Elizabeth was terrified to walk the streets in search of food in case she’d be hauled away and deported to a concentration camp or taken to the Danube and shot.

The words from László’s last postcard resonated deeply as I reread them: “Darling, I hope that you are fine, why did you have to [quit] your work, I hope that you do not have any serious problem. I am happy that you moved together with Mom, at least she is not on her own, and she can help you a bit. My dear, please take care of yourself and Ágika, I am very worried.”

Elizabeth described to me how she had survived one close call when she went out to find bread for Ágika. Arrow Cross Nazis in green army fatigues dragged her to the Danube, which was red with blood. She recalled looking down in terror, seeing bodies floating all around.

Elizabeth’s wrists were tied behind her back with wire. Groups of people would be tied together, some shot, while others were left to drown once they were pushed off the edge of the steep stone embankment. Elizabeth was tied to an elderly Jewish man. As a member of the Arrow Cross raised his gun to execute them, a group of low-flying Russian planes strafed the sky. The Arrow Cross ran for cover. Elizabeth stood in disbelief as she freed herself from her fellow captive and fled back to Ágika.

By December 1944, the Nazis, sensing the war was lost, continued with their plan to exterminate the Jews and encircled the ghetto with dynamite. The Soviet Army reached Budapest before the explosives were set off. Hitler commanded his soldiers to defend the city to the last man. This resulted in street-by-street battles. When the Budapest ghetto was liberated on Jan. 18, 1945, Elizabeth said she and her mother staggered out carrying Ágika, who at almost 15 months old was “too weak from malnourishment to even crawl.”

After the war, men from the labour battalions who had survived the death march from Bor returned to Budapest. Two men who had been with László told Elizabeth the news of his death. I asked my grandmother what her thoughts were when she heard this. She said she sat on a crumbling street curb and cried for a long while.

As a young widow and single mother, the only thing she could do was push past her broken heart. Her focus was ensuring their survival after losing their home, their possessions and László. The Hungarian and German fascists also murdered most of her immediate and extended family — her 16-year-old brother, Tibor Grün, their father, Vilmos Grün, her brothers-in-law, her maternal grandfather, aunts, uncles, cousins. She described building a wall around her heart to keep it from imploding. That wall remained in place for the rest of her life.

Life after the war was impossibly hard. There was no work. With the help of the American Jewish Joint Distribution Committee, both Elizabeth and Ágika received food, clothing and money, which is how they survived until 1948 when the Hungarian economy began to revive. However, Elizabeth feared the rising and virulent antisemitism she continued to experience in post-war Budapest. She and Ágika escaped Hungary in 1956 after the violent Hungarian Revolution.

Elizabeth died on Oct. 4, 2019. She chose a medically assisted death and left this Earth on her own terms. I cry when I say mourner’s kaddish for László and Elizabeth during Yom Kippur services — another holiday when Jews remember those we loved and lost during the Holocaust. I think about László a lot, somehow feeling his presence all year round. I trace the shape of my nose, the curve of my eyes and see some of him in my own face. I am weighed down by the guilt that I’m here and he isn’t; that I have outlived him. Giving myself permission to enjoy the big and little things in life that László never had a chance to experience has been a lifelong struggle.

László’s postcards remind me of how important it is to keep retelling the story of my family’s slavery and survival. Just as Jews are required to tell the story of Passover, I feel the need to tell the story of my grandfather — of modern slavery and its brutality. I’m sharing his story for this generation and the next, for those who think the Holocaust is something Jews should move on from and, most importantly, for those who deny it happened or that it could ever happen again. I owe it to László, who was 27 when he was murdered. It was because of him that I received the most precious gift: my life.

***

Carol Moskot is Broadview’s art director.

This story first appeared in Broadview’s April/May 2023 issue with the title “The last letters.”

Heart rending. But why in Broadview now? I have protested in the past about how Jews are selectively portrayed in liberal religious media (including back in Observer days). The best explanation for my “discomfort” with this article is to be found in Dara Horn’s now well-known book “People Love Dead Jews: Reports From A Haunted Present”. It is to cry.