Truth and justice walk hand in hand, so the federal government, RCMP and churches must be held accountable for what happened at Alberni Indian Residential School, Tseshaht First Nation elected chief councillor Wahmeesh (Ken Watts) told Broadview. The comments came after Tuesday’s announcement that researchers have documented 67 deaths and geological scans have found 17 potential unmarked graves.

Survivors are clear that they want the United Church, which ran the school in Port Alberni, B.C., from 1925 to 1969, and the federal government to revisit previous apologies in light of recent information and research. Tseshaht is also calling for an independent investigation into the RCMP’s role in taking children from their homes, Wahmeesh said.

You may unsubscribe from any of our newsletters at any time.

“I hope people really heard the calls for justice. One of our survivors said that if nothing happens out of this and nobody’s held accountable, then what was the point in doing all the work,” he said.

Funding for projects such as demolition of remaining Alberni Indian Residential School buildings, continued research and scanning, construction of a wellness centre and memorialization of children who died are also priorities, he said.

Rt. Rev. Carmen Lansdowne, moderator of The United Church of Canada, said the denomination is committed to being accountable and ensuring that apologies are backed up by concrete acts of reparation.

“The church will not look away from the truth that continues to be uncovered,” she said. “We were wrong to participate in this colonial, racist and oppressive system.”

Lansdowne, a member of the Heiltsuk First Nation whose relatives attended residential school, said the information about Alberni is difficult for all Indigenous people.

“We [as a denomination] apologize to the children’s families and the communities for our actions and for not listening as we should have as we were told over and over again for decades about the children and the burial sites and the deaths that were taking place at the Alberni residential institution,” Lansdowne added.

All communities impacted by United Church-run residential institutions can apply for help from a special fund, she said.

“In addition, the Pacific Mountain Region has committed an initial $1 million — and are well on their way to raising that — for a healing centre. That’s been in conversation with the leadership of the Tseshaht First Nation,” Lansdowne added.

Help for all those affected by the research is in place on Tseshaht First Nation. While some are struggling, others feel relieved that their stories are being told, Wahmeesh said.

More on Broadview:

- Scan of area around Alberni Indian Residential School reveals evidence of potential graves

- Giving land back and other ways Canadians are making reconciliation personal

- These Indigenous groups are helping youth aging out of foster care

Nora Martin, who attended Alberni from 1968 to 1973, was anxious about attending the announcement, but found some relief in knowing that people are finally listening to survivors’ stories.

“I want revised apologies from the government and the churches and the police that took part in apprehending children and taking us away from our communities,” Martin said.

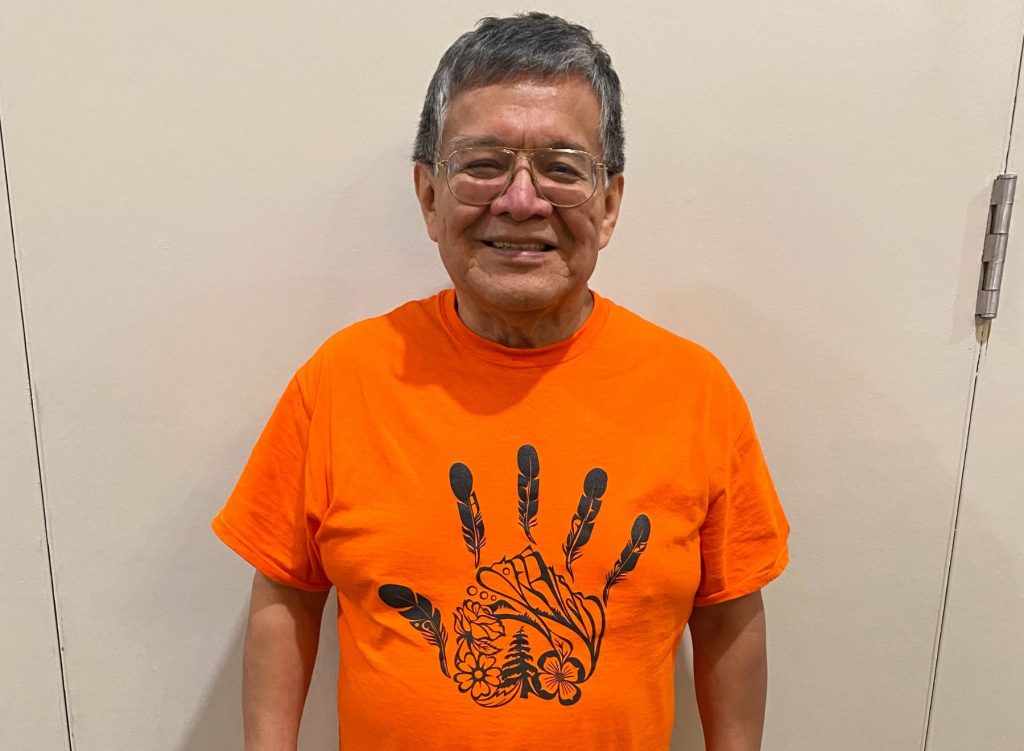

Chief Willie Blackwater (Tsa Bux), who was chief plaintiff in a historic 1995 court decision that saw Alberni dormitory supervisor Arthur Henry Plint jailed for assaulting 16 Indigenous boys, said news about the deaths and potential graves is painful.

“But I have done a lot of personal healing over the years,” said Blackwater, who, after leaving the school, was diagnosed with post-traumatic stress disorder.

“Personally, the teaching from my elders and traditional healers is that you can’t move forward if you don’t forgive.”

The ultimate test was to visit Plint in jail and offer forgiveness, he said.

Everyone has their own path to healing, said Blackwater, but he still has difficulty reconciling the role of the churches in residential schools.

“They knew full well what was going on and the government knew full well what was going on, but they did nothing,” he said.

If you are a residential school survivor or have been affected by the residential school system, you can call the 24-hour Indian Residential Schools Crisis Line at 1-866-925-4419.