Content warning: This story discusses stalking and femicide and may be upsetting for some readers.

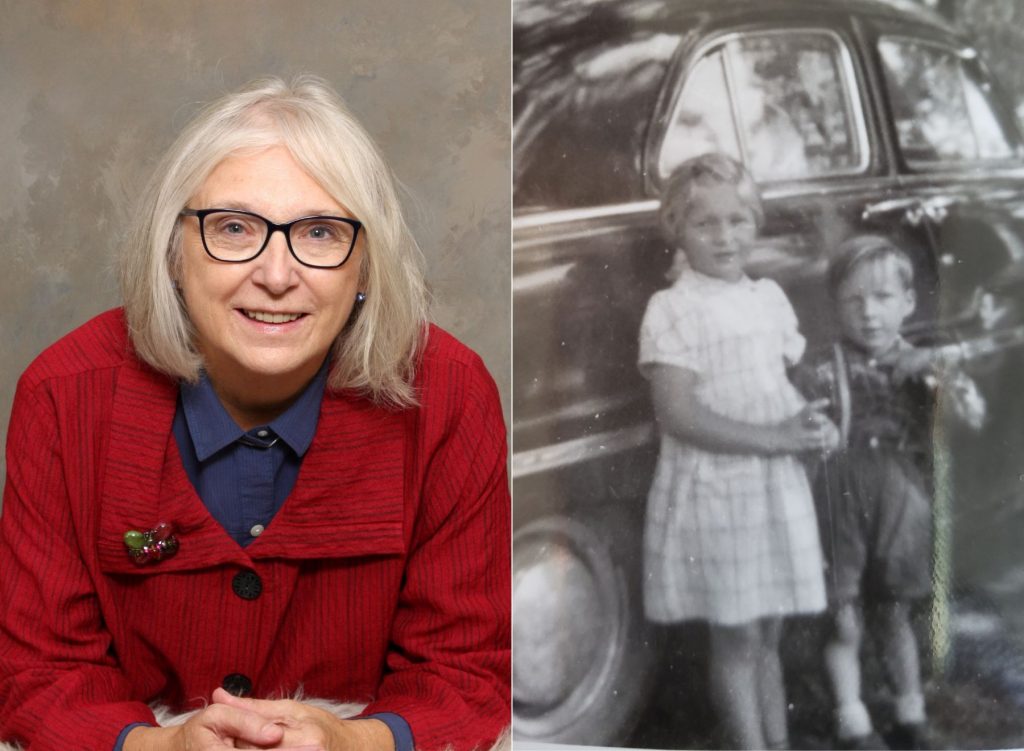

On a fateful day in 1963, in the rural hamlet of Castleton, Ont., a former United Church minister shot to death all the women in his family, save one. In a recently released memoir, survivor Margaret Carson bears witness to what her family suffered all those years ago. In vivid detail, she and her cousin and co-author, Sharon Anne Cook, painstakingly reconstructs the events leading up to the massacre, drawing on family memories, interviews with witnesses and archival documents. What would possess a once-respected scholar and cleric, they ask, to stalk and then slaughter his female kin?

You may unsubscribe from any of our newsletters at any time.

Far from a sensationalist crime novel, The Castleton Massacre: Survivors’ Stories of the Killins Femicide is an absorbing family memoir that shines a light on the history of femicide in Canada. It honours the voices of the victims —four women and girls, as well as two unborn children — while asking probing questions about whose lives get mourned and marked and whose merely forgotten.

It also humanizes murderer Robert Killins. No one emerges from the womb evil. How, it asks, did a beloved brother and son become a vicious killer? An impulse to make sense of the incomprehensible gives rise to meticulous research on the part of the authors.

Nothing remarkable surfaces about Killins’ childhood, though he was the uncontested “star” of his family. Glimmers of trouble first emerged when he began his studies at Queen’s University in 1924: he vilified some authority figures and revered others, was undisciplined to a fault, and became easily angered and sometimes explosive. Most concerning was the hatred he betrayed toward anyone of a different race or religion. In Cook and Carson’s words, “he disparaged evangelical Christians as ‘ignorant’ and Roman Catholics as ‘benighted.’” During the period of the 1920s, he was also an active member of the Ku Klux Klan.

Ordained in 1932, Killins became a so-called man of the cloth at a time when the newly minted denomination of the United Church was trying to instil the values of British Protestantism into the fibre of Canadian society. What might unsettle any current member of the church to know is that he would have deeply identified with the project of white civility at the heart of Canada’s largest Protestant denomination.

Killins wasn’t only racist but also recalcitrant. He sparred with church councils and committees, and couldn’t seem to make it work with any one congregation. But through his ministry, he, at 30, met 17-year-old Florence Fraser. From the start, Killins was condescending and demanding, treating her like a child rather than his future life partner. Fraser’s mother, however, was enamoured with his status as a minister, although his arguments with church officials would worsen after the wedding. Soon, Killins would break with the United Church entirely.

His career in ruins, he retreated further and further from society, and Florence Killins, by then a young mother, was increasingly isolated. Eventually, she fled, on foot, with their infant daughter. With no supplies or food, she made her way by train from Ruskin, B.C., to eastern Ontario, where she started over again. A new relationship followed, as did more children.

So too, did Robert, who terrorized Florence. He built a shack on the property she shared with her common-law partner. He also relentlessly threatened both her and their daughter for almost 25 years.

Compounding the burden for rural women is geographic isolation, fewer community resources, and other constraints in smaller districts and towns.

The fact that the Castleton massacre took place in an out-of-the-way enclave, away from the media spotlight, might explain why it remains a relatively unknown event in Canadian history. Arguably, class prejudice also plays a role in the obscurity of this specific case. As Cook and Carson point out, while Killins had once been “solidly middle class as a student and cleric,” he still “held an ambivalent class position.” Toward the end of his life, he was destitute and economically marginalized. Meanwhile, the authors speculate, community organizations like the local choir and United Church women’s group likely wouldn’t have embraced Florence Killins.

Cook and Carson’s memoir gives a voice to the victims. It honours the women and girls — four in total, as well as two unborn children — who died that day. It also asks us to listen to survivors. There is much to be learned from recognizing them as the experts in ending a scourge that has only intensified during the pandemic.

EDITOR’S NOTE: This story has been updated since publication for wording-based changes. There have been no fact changes.

***

Julie McGonegal is an associate editor at Broadview.

“No one emerges from the womb evil.”

YET – Romans 3:23 “For ALL have sinned and fall short of the glory of God.”

No one teaches a child to lie, but they know how to do it.