Two dozen people — including a longtime Quaker, a Muslim woman, several ex-Catholics and a humanist officiant — sit in a circle in a room at the multifaith centre at the University of Toronto. Incense from a nearby Hindu meditation group wafts through the open door. The gathering is the newest of 11 (mostly U.S.) chapters of the Oasis Network, a secular organization that seeks to unite people based on their shared lack of belief.

They meet on Sunday mornings, listen to speakers, play music, pass the offering plate and drink coffee. It may look like a church and be organized like a church, but whatever you do, don’t call it a church.

You may unsubscribe from any of our newsletters at any time.

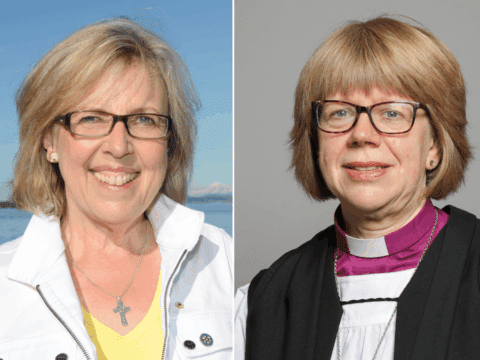

“We don’t see ourselves as a church. We’re building a community,” says Eve Casavant, who was inspired to help start the chapter after hearing Rev. Gretta Vosper preach at West Hill United in suburban Toronto. (West Hill has a formal affiliation with the Oasis Network, and Vosper serves on its board.)

Oasis is part of a growing trend of formal secular communities, including the Sunday Assembly, the Centre for Inquiry and independent groups such as the Calgary Secular Church, that appeal to atheists, agnostics and questioning theists who want the structure of old-time religion without the doctrine.

They meet in libraries and community centres and convene for Sunday “services” as well as pub nights and potlucks. They have their own commandments (although they prefer to call them principles), such as “People are more important than beliefs” and “Question everything.” They’re also fond of slogans: “Empowered by reason. Connected by compassion” (Oasis) and “Live better, help often, wonder more” (Sunday Assembly). Attendance is small — at least in Canada — but media attention has been big. “Atheist church” makes a good headline.

Sunday Assembly, which began in England in 2013 and has grown to 70 chapters in eight countries, has had only limited success in Canada: several chapters either failed to launch or stopped operating, although one is thriving in Halifax.

Seanna Watson, who was an active member of Kanata (Ont.) United for years until she realized she was an atheist, helped found the Ottawa chapter of the Centre for Inquiry, where she attends

the regular Secular Chat and Living Without Religion meetings. She also served as an adviser to the struggling Sunday Assembly Ottawa chapter. “What was needed was a dozen people willing to put in 10 hours a month. So far we haven’t been able to find that.” Without the real estate and staff resources of traditional churches, it remains to be seen whether these secular communities will survive.

Maria De Leeuw travels an hour one Sunday a month from Olds, Alta., to attend the Calgary Secular Church. She admits the word “church” has been problematic for some atheists who associate it with what they’ve disavowed in the first place. “We’ve discussed getting rid of the word ‘church’ in our name, but that’s what we are — we gather to talk about ethics and how to live our lives. Isn’t that that the purpose of church?” she asks. “For centuries, Christian churches have been moving towards secularism. We’ve just skipped right to the end.”

Back at the Toronto Oasis Sunday gathering, the focus is on identifying causes the group wants to advocate for, including Indigenous issues, helping refugees and political engagement. The discussion descends into crosstalk and interruption. Finally, the Quaker says, “There are a few people who we haven’t heard from at all — how about we let them do some of the talking?”

Secular communities, it appears, are just as complex as any church.

This story originally appeared in the October 2017 issue of The Observer as part of the regular “Spiritual but Secular” column.