Content warning: This article discusses people’s experiences with residential schools, which may be triggering to some readers.

The date is July 17, 1849. The place is a field 30 kilometres southwest of London, Ont. The weather is warm and sunny. Anishinaabe and Oneida nations are present in significant numbers. The Province of Canada and the British Crown are represented. Kahkewaquonaby, an Anishinaabe chief and Wesleyan minister, assists the president of the Conference of the Wesleyan Methodist Church in Canada. Rev. Egerton Ryerson, superintendent of education for Canada West, looks on approvingly.

You may unsubscribe from any of our newsletters at any time.

Together, they are laying the cornerstone of the Mount Elgin Industrial Institute. Unbeknownst to them, they are also laying the foundation for the legacy of residential schools in the future United Church of Canada.

Many eyes are on Kahkewaquonaby. Known for his strength of character and physical endurance, he is somewhat stooped and frail from a recent illness. The passion he has for this endeavour, however, is in no way lessened. He is not alone in his commitment to the school, a fact that may surprise us today. Indeed, Indigenous people take ownership of the project, contributing the land and a quarter of the annual treaty money they receive from the government to pay for the school themselves. The Methodist church — to which many Anishinaabe people belonged — supports the venture as well.

The proceedings on that historic day are translated into Anishinaabemowin. The final blessing is said in Anishinaabemowin by an Indigenous minister, Rev. John Sunday. Following the ceremony, the settlers in attendance are guests at a feast provided by their Indigenous hosts. An article in The Christian Guardian — which would later become The New Outlook, The United Church Observer and then Broadview — said of the event that “Nothing was left to wish for — nothing to regret.”

But for us today, there is terrible irony in these words.

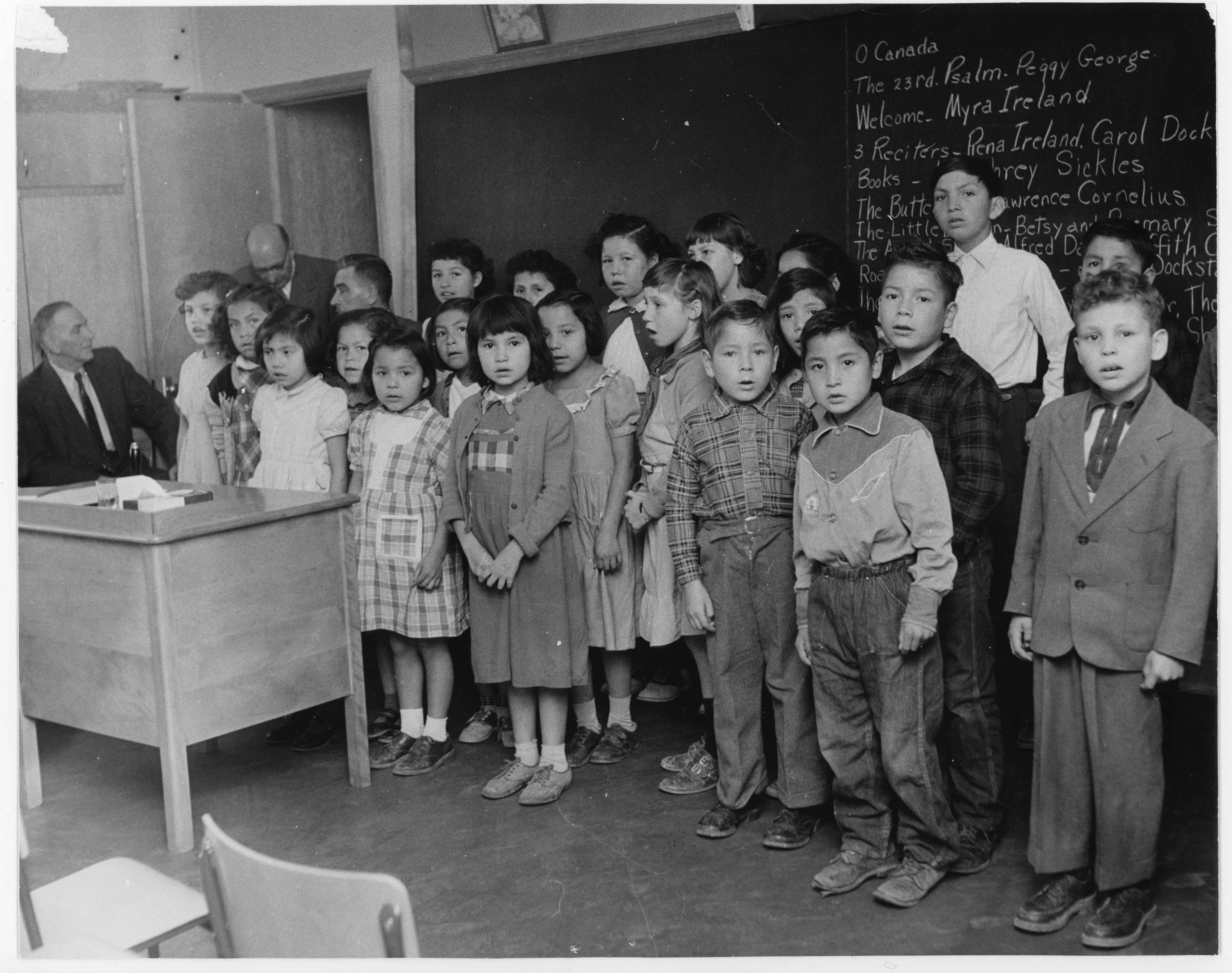

This story is the beginning of an answer to the question of how the United Church got into the business of residential schools. The images of Indigenous leadership and a happy feast stand in shocking contrast to the stories of residential schools that we hear today — stories of abuse, of forced abandonment of language and culture, and of unmarked graves at sites across the country.

This beginning, happy as it may sound, does not erase, lessen or justify the crimes of the United Church. Rather, it brings into sharp focus the betrayal suffered by the Indigenous people who participated in that cornerstone laying, and that of their descendants. In the end, what they hoped for, worked for and agreed to was replaced by something that had little to do with what they envisioned or wanted. It was designed instead to take from them what they had.

Some might begin the story of residential schools in 1879 with the Macdonald government’s scheme to settle the West. Some would begin in the 17th century with the first French colonies and missionaries. The Truth and Reconciliation Commission begins it in 1492 with the Doctrine of Discovery. We could keep going.

This is not to say we can’t identify the origins of residential schools. They are there for all to see and are not far from us. Many of the same impulses continue to reverberate through Canadian society and beat within our hearts today.

For the Indigenous people who helped found Mount Elgin Indian Residential School — as it would become known — and for other Indigenous communities who wanted schools for their children, western education was a carefully considered survival strategy. They found themselves sharing the land with more and more European settlers. Schools were a project they believed in.

They imagined that they would have an increasingly central role in them, and had plans to train and appoint their own teachers and principals. Kahkewaquonaby wrote of “our intention to select from each School the most promising boys and girls, with a view of giving them superior advantages.”

The earlier experiments with day schools by the Anishnaabeg in southern Ontario had a bilingual curriculum printed in both English and Anishinaabemowin. Indigenous communities imagined that they would benefit their children, allowing them to prosper as Indigenous people alongside the newcomers. But the forces of colonization and then of nationalism quickly suffocated those hopes.

Less than 10 years following the opening of Mount Elgin, many of those who had celebrated its beginning were already feeling deep regret and disappointment. Kahkewaquonaby, the chief they had hoped would be principal, died before he could start. All lessons thereafter were English-only. Children spent too much time working in the fields or learning religion and not enough time working on the three Rs.

The situation would only get worse. By the time of Confederation, the Canadian government felt little compulsion to listen to the concerns of Indigenous parents regarding any of the schools that had been established. It passed the notorious Indian Act that made Indigenous people wards of the state, and instituted a program of Indigenous education whose central pillar was the separation of children from their parents and culture. Roman Catholic, Anglican, Methodist and Presbyterian denominations were willing partners. Indigenous peoples themselves were never consulted.

The government-church partnership was toxic. Churches loved getting money to build and run schools and were jealous if competing denominations got more. The government, however, would never give the churches enough money to properly run the schools.

The churches were addicted to the funding and prestige of government support. They could neither refuse the money nor mount a serious criticism of the system in which they were entangled, even though they could see it was harming children. Indigenous communities, reeling from the loss of their land, way of life and freedom, protested but were ignored.

This situation reached its lowest point right around the time the United Church was born. And the formation of the United Church did nothing to make it better.

Strictly speaking, the United Church did not “get into” residential schools; it absorbed them. When the Methodists and two-thirds of the Presbyterian denomination joined with the Congregationalists in 1925, they brought their schools with them — 12 in total. The United Church took over these schools and inherited their legacy.

There are more schools that form part of the United Church’s residential school legacy not included in that total. Some opened and closed before the United Church had even come into existence. An example is the Regina Indian Industrial School (RIIS) that opened in 1891 and closed in 1910. Reports of sexual abuse and horrific conditions at RIIS had been sent to church officials in the early 1900s. Recently, the United Church, together with the Presbyterian Church in Canada, accepted responsibility for preserving the gravesite connected to that school. It is a shared legacy.

Two more, Morley and Teulon, were residences at the time of church union. Morley became an Indian residential school in 1926. Teulon remained a residence only, but was also the site of abuse and neglect of children under the care of the United Church.

(In addition to residential schools, the denomination ran dozens of day schools.)

Along with the residential schools, the church inherited the knowledge that they were ineffective and often dangerous places for educating children. There were accounts of students suffering terribly. The Canadian government had also received reports from school inspectors of extremely high death rates due to unhealthy living arrangements. Different church leaders and government agents who worked with Indigenous communities made shocking observations: more than half of the students were dying from diseases contracted at the school before they could graduate.

Despite these reports, it appears that few in the United Church knew or cared very much about the residential schools they had inherited. People were caught up in the triumph of church union. Their minds were captive to the dream of an English-speaking Protestant Canada.

The interwar period was the high-water mark for exciting overseas missions that promised to evangelize the world in a generation. Little thought was spared for the residential schools in Canada and their depressing record, even though a few voices in the wilderness had strongly denounced them as criminal.

Indigenous communities were not the only ones neglected by the new United Church of Canada. Those different in religion, language or culture, if they were considered at all, were thought to need civilizing. Immigrants, especially those from non-Protestant nations, were a source of anxiety in the church. Members worried they would undermine white Anglo-Saxon Protestant society, the ostensible foundation of a strong and prosperous nation.

French ministries were ignored and allowed to dwindle. If you didn’t speak English you didn’t seem to matter. In the first issue of The New Outlook magazine celebrating church union, Indigenous peoples and multicultural, multilingual Canadians were barely mentioned amid all the congratulatory talk about the new church.

The denomination may have had good intentions, but it was not wise or courageous enough to stand up to the darker impulses at work.

Mount Elgin kept running through the interwar years. There are stories of students who graduated and did well for themselves. But inside the historic barn building were messages engraved on the walls, a record to the misery many felt: “making a slave,” “walk on tracks for 2,000,000 miles,” “run away,” “L.E.W. was here on July 9th 1926 working like hell.” One survivor told the Truth and Reconciliation Commission of the “emptiness” that remained in the children’s hearts when schoolmates, sick with tuberculosis, were quietly taken away, never to be seen again.

The school was not closed until 1946. At this point, inspectors’ reports described it as “desperately understaffed” and “one of the most dilapidated buildings” ever inspected.

At about the same time, Canada began to wake up to the injustices suffered by Indigenous peoples. In the postwar stories of Nazi atrocities, many Canadians glimpsed a reflection of their own nationalism and prejudice. Many also noted the brave service that Indigenous soldiers had given to the war effort. They shuddered with shame when they realized how Canada was treating them and their families.

In 1946, the same year that Mount Elgin closed, the Canadian government created a special joint committee of the Senate and the House of Commons to re-examine the Indian Act and address historic wrongs. This was the beginning of the end of residential schools in Canada. In the process of the committee’s work, the United Church stated that it thought it was time to close residential schools and educate Indigenous children in public schools with non-Indigenous children. It took 23 more years for the United Church to completely extract itself from the running of residential schools and 40 more years before it began to apologize.

Very Rev. Stan McKay, former United Church moderator, records in his biography the way United Church residential schools made his family feel. For the McKays, who lived in the community of Fisher River in northern Manitoba, the only way for the children to get an education was to go to a residential school. The parents made a hard but necessary decision to enrol their children. Being United Church members, they chose the United Church residential school in Brandon for their two oldest daughters. To their consternation, the vehicle that arrived to take the sisters and other children on the long journey to Brandon over gravel back roads was a cattle truck.

At Brandon, the children very seldomly ate meat, and the education was not much use. The school did not adequately prepare the children to live independently in non-Indigenous society. But when they returned home, they found themselves on one side of a great culture gap that separated them from their parents.

How did the United Church get into residential schools? Perhaps there was love and a desire to help. The denomination may have had good intentions, but it was not wise or courageous enough to stand up to the darker impulses at work.

Turning again to the cornerstone ceremony at Mount Elgin in 1849, we see some of those impulses embodied in the dignitaries present. Lord Elgin, for whom the school was named, was governor general of the Province of Canada at the time and represented the British Empire, with the vast lands it conquered and exploited. Major E.T. Campbell, chief superintendent of Indian Affairs for the Province of Canada, stood for the Canadian state and the bourgeoning sense of nationalism that dreamed of a uniform culture, religion and language across a vast territory under its control. Rev. Matthew Richey, president of the Conference of the Wesleyan Methodist Church in Canada, represented the church that confused Christianity for western ways and values and sought to convert Indigenous people at the expense of just about everything else.

And of course, there is Ryerson, founding editor of The Christian Guardian, whose plans for the school became the blueprint for residential schools across the land. Slowly his name is being removed from churches, universities, schools and scholarships. But is the legacy he now represents truly being purged from Canadian society?

Impulses for power and conformity still reverberate throughout public discourse in Canada and throb in our economic centres. None of us are immune.

Support is available for anyone affected by their experience at residential school and those who feel triggered by this article.

A national 24-hour Indian Residential School Crisis Line exists to provide emotional support and crisis referral services for residential school survivors and their families.

It can be accessed by calling 1-866-925-4419.

It’s important to remember that even as the United Church was running residential schools, a significant number of Indigenous people identified as members of the church. Some of them, like Stan McKay and his sisters, attended residential school. Despite these experiences, many count themselves as committed members. It’s still their church, regardless of the fact that it inherited and ran residential schools.

When they are listened to, their words and experiences can form some of the medicine that heals — not only themselves, but the whole body of Christ.

Since the 1950s, more Indigenous voices have been heard in the church. Some have expressed anger at the way they’ve been treated. We Wai Kai Elder Alberta Billy’s demand for an apology from the 31st General Council in 1986 is credited with getting the ball rolling on truth and reconciliation in the United Church. Efforts at approaching forgiveness have also been expressed and heard.

The evil that the schools represent implicates the whole church, but for McKay, it’s also bigger than the church. It’s a mindset in Canada at large: that Indigenous people should be more like white people. It believes that rather than be taught to be part of a community, Indigenous children should be educated to be individuals who fend for themselves. “The church has been compromised,” says McKay.

Such rejection of loving community got the United Church mixed up in residential schools in the first place.

Going back to that fateful summer day in 1849, perhaps we can catch a glimpse of the road not taken. The Christian Guardian reported that “the Indians upon the mission had made arrangements for holding a commemorative feast.” Enough food, it said, was prepared for 300 guests. Here is a vision of abundance, sharing and fellowship.

How did the United Church get into residential schools? Too many of its members took the road of domination and competition over fellowship and sharing. Had more taken the second path, the history of the church would surely be different.

CORRECTION: A previous version of this story stated that it took until 1969 for the United Church to close its last residential school. That school was not closed, instead responsibility for it was passed to the Canadian government. This version has been updated.

***

Rev. David Kim-Cragg is a minister at St. Matthew’s United in Richmond Hill, Ont.

Vanessa Kennedy, who served as a sensitivity reader for this article, is an Indigenous consultant in Hillsdale, Ont.

This story first appeared in Broadview’s September 2022 issue with the title “A betrayal of trust.”

I enjoyed the article, it’s been a long while since I’ve taken Canadian history, and this was one of the topics of discussion set forth in the late 70’s (this is not current history).

“How did the United Church get into residential schools? Too many of its members took the road of domination and competition over fellowship and sharing. Had more taken the second path, the history of the church would surely be different.”

I don’t think the members had the concept of domination and competition. This was a good idea gone bad. Whether it was intentionally meant to go bad is a different story. If so most people would not have supported it, if they had known.

Myself included instead of “making disciples” we are “forcing beliefs”. Instead of letting God call others to Christ we try to do the calling ourselves. Often we forget that as Christians we have God’s Spirit, and those who do not are blinded to the Truth. It’s like a visually abled person yelling to a blind person not to cross the freeway, we know and see the danger, but the Spiritually blind do not.

I doubt the history of the United Church would be different if it did not take up the Residential Schools, it is too caught up in other social matters. One thing is for sure, there would be a lot less apologizing.

“The churches were addicted to the funding and prestige of the government support”. That fact is occurring today with the government financial support from the anti-racist programming and the “BLM Mission ” work, extracting time. talents, treasures and jobs to further the hate and anger in the church and all over the world. To the family, friends and co-workers of Andrew Hong I give my sincerest condolences. Loving God, when life leaves me road weary and thirsty thank you for the gift of your spirit, the living water, who dwells in every believer. Rest in sublime peace and in eternal love Andrew Hong.