On a sunny December afternoon in Kingston, Ont., about a dozen people gather by a massive white oak tree a few metres from the shore of the Great Cataraqui River. Poems and other written messages are attached to a fence in front of the oak. “She sits among friends/The targets of their stupid greed/Let their beauty be,” proclaims one message sealed in a Ziploc bag.

Laurel Claus-Johnson, a Mohawk elder, has organized a gratitude ceremony for the 220-year-old tree. The developer who owns the vacant property on which it stands won’t let anyone on the site, so Claus-Johnson and her friends have tied a length of yellow ribbon to the fence, signifying their solidarity.

You may unsubscribe from any of our newsletters at any time.

Midway through the ceremony, Claus-Johnson asks a woman lingering nearby if she’d like to speak. She is Latoya Powder, a planner and de facto spokesperson for the developer, who says she has come as a private citizen but seems eager to defend her employer. “Man has scarred this site for years, I agree,” she says. “It should be protected, and it deserves to be cleaned up.”

“Man does not know how to clean up,” Claus-Johnson retorts. “Man knows how to destroy.”

The sparring that ensues reflects years of discord over the future of the site, a 15-hectare parcel known locally as the Davis Tannery, after a leather-making factory that was located there. It closed and was abandoned in the mid-1970s, leaving a legacy of grievously poisoned soil and sediment. The wrangling has intensified since 2017, when a local developer submitted a proposal to the city that includes decontaminating the site and constructing more than 1,500 housing units in medium-rise buildings near the riverfront. In recent years, formal and informal groups have sprung up around the health of the river, the protection of trees and wildlife, gentrification and homelessness.

But it’s more than a local flashpoint: the debate over the future of the Davis Tannery echoes existential issues facing communities globally. Depending on your vantage point, it’s a story about economic inequality, the climate emergency, resource exploitation, environmental degradation, species bias and the denial of fundamental human rights. It’s a reminder that sometimes you don’t need to look any further than your own backyard to see the forces that shape our world, for better or for worse.

Over the years since it was abandoned, the former tannery lands have mutated into a site of contradictions and complexities. Atop the wretched, toxic soil and sediment, a thicket of vegetation, rushes and trees has sprouted alongside the faithful old oak. Squirrels, rabbits and birds scurry under felled limbs, and in the warmer months, turtles lay their eggs nearby and share the shoreline with huddling ducks and herons. More recently, they’ve been joined by unhoused people who’ve been evicted from community encampments and have made temporary homes on the tannery lands.

To the north, the site is bordered by Belle Park, which was a landfill and later a golf course before being turned into a public park. To the south are residential, commercial and recreational centres, including rowing facilities. Its eastern edge is located along the widening of the river known as Inner Harbour, while a mix of small businesses, light industry and housing borders its western perimeter.

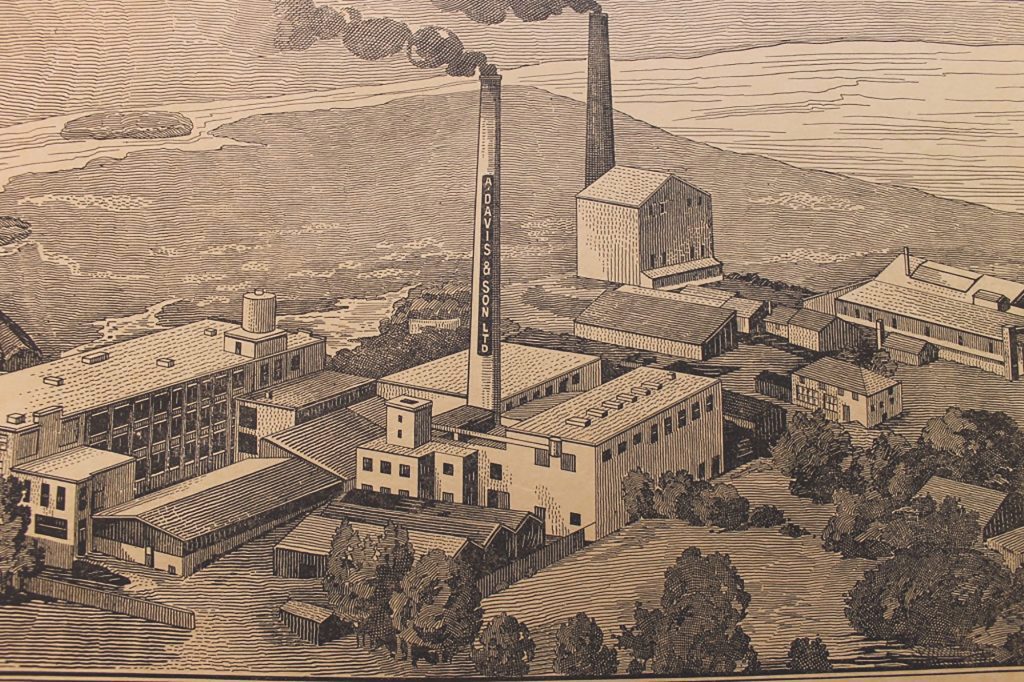

The site has been closed off since the 1980s, but the damage to its soil and groundwater had been done decades earlier. Tannery operations on the property date back to the mid-19th century. Its proximity to Lake Ontario, the Rideau Canal and rail transportation caught the attention of A. Davis and Son, which purchased an existing tannery operation on the site after a fire destroyed one of the company’s other plants in 1903. It was one of Kingston’s largest employers and one of the biggest tanneries in Canada. A lead smelter also operated on the site.

The tannery shut down in 1973 and was eventually demolished. The land was subsequently declared a brownfield site — a provincial designation for properties that are “vacant or underutilized places where past industrial or commercial activities may have left contamination (chemical pollution) behind.” Dangerous levels of chromium, lead, mercury and PCBs have been detected at the site. A 2019 report to Kingston City Council described it as “arguably the largest and most contaminated brownfield property within the city of Kingston.”

The Davis Tannery lands were the subject of numerous studies, consultations and community initiatives as they sat derelict and in tax arrears for decades. An attempt to clean up and redevelop the site failed in the 1980s. In 2004, the province passed legislation that allows potential developers to purchase brownfield lands and write off municipal taxes and other expenses against the cost of cleanups. The legislation breathed new life into efforts to rehabilitate the site. A developer purchased the property from the city in 2006 and spent several years trying to cobble together a redevelopment scheme. It failed to materialize, and in 2017 the site was sold to Patry Inc. Developments.

Owner Jay Patry is well known in Kingston as a multi-unit residential developer and property manager. In 2013, his company made national headlines when a student housing complex under construction near Kingston’s downtown caught fire and burned to the ground, stranding a crane operator high above the flames. The operator clambered out onto the crane boom and suffered burns to his legs, buttocks and hands before being rescued by a military helicopter. Patry’s company and three individuals including company owners later pleaded guilty to numerous workplace safety infractions and were hit with fines totalling $74,000. Patry made news again in 2018 when he climbed to the summit of Mount Everest, then less than 24 hours later, scaled nearby Mount Lhotse, the fourth-highest peak in the world. Patry, who was 39 at the time, claimed he was the first Canadian, and one of only 30 climbers worldwide, to have climbed both mountains in a 24-hour period.

His plans for the tannery lands are no less ambitious. To build the housing he proposes, he wants to clear the site of vegetation — including the oak tree that was the focus of last December’s gratitude ceremony — grub the ground of debris and remediate an estimated 550,000 tonnes of soil by disposing of it off-site, stabilizing it on-site or reusing it. One of the more contentious aspects of Patry’s plan involves capping a marsh area on the north end of the property — part of a provincially designated “significant wetland” — with a layer of clean soil, which could result in a redrawing of the wetland’s boundary and a revision of its zoning status. The price tag for the cleanup is estimated to be a staggering $70 million, with Patry eventually recouping up to nearly $64 million in tax rebates and other concessions under the city’s Brownfields Community Improvement Plan.

Kingston City Council unanimously approved the financial component of the cleanup plan in 2020. Patry’s development proposal, including adjustments to a number of local bylaws, is currently under review by city staff. Rob Hutchison, the councillor for the ward that includes the tannery site, thinks Patry’s asks are too grand. But he says the approvals process has to play out. “Staff would say it’s a new development application and we, under the Planning Act, have to consider it as such.…By law, we have to take this application on its face value.”

Requests for comment from Patry were directed to his staffperson Latoya Powder, who declined to be interviewed for this story.

Nearly everyone agrees that the site would be better off decontaminated. The devil is in the details — when you unpack them, you see a multitude of global struggles creeping into a local concern.

Case in point: Mary Farrar and her turtles. The president of a community group called Friends of Inner Harbour, the 81-year-old Farrar was at the December oak tree ceremony. A week earlier, she told me how she came to be known as Kingston’s “turtle lady.” For more than a decade, the city considered extending a street through a park next door to the tannery. Farrar, concerned about the impact of paving over part of a waterfront park, was looking for allies to help stop the extension. She found turtles.

Turtles are threatened almost everywhere you look on the planet. The northern map turtle — so named because the lines on their upper shells resemble the contours on a topographical map — was included on the list of species at risk in Ontario in 2008 and again in 2013. About 100 of them nest on lands that would have been decimated by the street extension project. Farrar dedicated years to studying the turtles and protecting their nesting grounds. Walking through the area, I noticed small wooden structures topped with chicken wire, testimony to her efforts to protect turtle nests from predators and stomping.

Farrar’s advocacy work eventually won out; the street extension is all but dead, and the turtles are beloved local fixtures. But they’re still threatened. Decontaminating and developing the tannery shoreline would uproot a favoured basking place. “If the development goes ahead, the turtle habitat will be obliterated,” says Farrar. Her group’s Facebook page urges residents to register their concerns with local politicians. “The shoreline should be left to Nature to remediate,” it declares. “It is arrogant to think that humans know better.”

Farrar also belongs to a group called No Clearcuts Kingston, which opposes the removal of an estimated 1,800 trees from the Davis Tannery site as part of the decontamination project, and which rebukes the city for allowing the site to be deforested when expanding the urban tree canopy is part of Kingston’s official response to the climate emergency. No Clearcuts shares common cause with another recently formed organization, River First YGK, an advocacy group focused on the impact on the river and wetlands of the tannery proposal as well as a proposed cleanup of lands owned by Transport Canada adjacent to the tannery site.

On a late November afternoon whipped by wind and wet snow, historian Jeremy Milloy, River First YGK’s co-ordinator, gestures past the chain-link fence along the tannery’s marshy northern side. “We live in a climate emergency, and what is this?” he says. “This is a wetland. It’s a river running through a wetland into a lake, and it’s extremely at risk of flooding as our weather becomes wetter and wilder over the next 50 to 100 years.”

Like his counterparts in No Clearcuts, Milloy worries that removing trees on the site will encourage erosion and increase the risk of flooding on the catastrophic scale experienced in British Columbia last fall. The challenge, he says, is to convince civic leaders and the local population that Kingston is a frontline community in the climate emergency. “There’s not a pipeline. But people here are river people. This is a watershed community.” Just as grasping the scope of the climate emergency demands a holistic appreciation of the planet and its natural systems, the city and developers need to shift from a top-down view of the local ecosystem, Milloy says. “We’re trying to take the river in all its complexity and contingency and conflict, between being a very beautiful, vibrant space and a toxic, compromised space, and have it dealt with on its own terms rather than just another parcel of land.”

A rendering of Patry’s proposed project in its finished form imagines four mid-rise buildings arrayed in the sunshine along the riverfront, with a green belt and walkway separating the structures from the shoreline. The development application calls for a total of 1,509 apartment and condominium units and about 5,000 square metres of ground-floor commercial space. It also includes private and public park space and a boathouse for a local rowing club.

Prices for the townhouse-style units envisaged in Patry’s plan jumped locally by more than 30 percent last year. Add to this the development’s prime waterfront location, and it’s a safe bet that the units Patry hopes to sell won’t come cheaply. Same with the units earmarked for rental. And that’s before the cost of decontaminating the site is factored in. “He has to be able to make so much money off the property in order to pay for the cleanup costs,” says Coun. Rob Hutchison. “Honestly, I don’t know why he bought the property.”

Housing — or lack of it — is a major issue in Kingston. In part due to large student populations at Queen’s University and St. Lawrence College, the city has historically registered one of the lowest rental vacancy rates in Ontario. A recent surge in housing starts has improved the outlook, but the increase in vacancy rates has been accompanied by a spike in rents.

Tim Park, Kingston’s director of planning services, says almost 4,000 new housing units are currently slated for construction in the city, but “like any commodity, it’s up to the owner to adjust rental rates.” While Park says the city has requested that the tannery development include affordable housing, he cautions that “right now, the city just has a statement that a certain percentage should be affordable units, but there’s no way to enforce or implement it.”

The tannery lands could eventually be home to several thousand people. At present, the only residents are people like Donnie. In late December, Donnie (who asked to be identified by a nickname as he’s camping on private property) spent his 28th birthday alone near the banks of the frozen Cataraqui River, in a green pop-up tent and some blue tarps set up among fallen trees. He’s been camped out for a few weeks after leaving a homeless shelter. A couple he knows is camping nearby, and he’s envious of the companionship. “I’d give my f—king legs to have someone to talk to and stay warm with in my tent,” he says. “Even just the heat from their body.”

Donnie was born on a First Nations reserve in northern Ontario but grew up in group and foster homes. After he was arrested and incarcerated in 2020, his marriage fell apart and he lost his kids. When he was released last fall, he had nowhere to go and no money. He stayed at the shelter for a while, but it wasn’t a great fit. In the woods, no one harasses him except the animals who also live there. A few nights after Christmas, Donnie skirmished with a fisher and raccoons who wanted his leftovers.

Donnie bristles when he hears about the proposed re-development of the tannery lands — and the suggestion that it could help with Kingston’s housing and affordability crisis. “Who’s it affordable for? It’s not going to be affordable for poor people and homeless people,” he says.

He even speaks up for his raccoon neighbours, asleep in a tree near his tent. Shouldn’t they be considered in this, too? “People already live here,” he says indignantly. “It’s where I live.”

Beyond the fences marking the edge of the tannery lie once-thriving working-class communities that slid into decline in the 1970s as industry closed or relocated. For years, the district was regarded as Kingston’s poorest, but like similar districts in countless Canadian cities, it’s now undergoing gentrification as house hunters and small businesses are lured by lower real estate prices.

In spite of the recent changes, the district is still where you’ll find most of Kingston’s unhoused population, many of whom gather and camp around the nearby Integrated Care Hub, a facility that offers food, safety, shelter and counselling services to the vulnerable. Only one adult emergency shelter remains in Kingston. In September 2020, after unhoused people set up an encampment in a park, the city evicted the residents and removed their belongings. Since then, the city has done little to address systemic housing issues, aside from funding a non-profit’s pilot project to provide 10 sleeping cabins and a warming centre during the winter months.

People who work with Kingston’s poor take a dim view of the time, energy and resources the city mobilizes in the name of private, for-profit developments like the Davis Tannery lands, but not for issues like the affordable housing crisis. An Inner Harbour man, who wants to be known only as Jordan because he fears for his job with a local shelter service, says arguments that laud the tannery development as a solution to Kingston’s housing problems ring false. “The people who are affected by the housing crisis are people who would never be able to even consider living [there],” he says.

In fact, he continues, it’s more likely that the plan would worsen the city’s already considerable wealth gap. “Building a luxury development in a traditionally low-income area is going to actually amplify the housing crisis when thousands of people with more money move into this neighbourhood,” he says. “It’s always the low-income areas near a downtown core that start to get more and more development until the people who have lived there for decades eventually have to move out.”

Canada and other nations recognize access to adequate shelter as a fundamental human right. But here as elsewhere, it often seems that it’s more of a right for some than it is for others.

A week before we met at the edge of the Davis Tannery lands, Jeremy Milloy of River First YGK had listened to a talk by journalist Andrew Nikiforuk. Something Nikiforuk said stuck with him: “The study of ecology is the study of consequences,” Milloy recalls. He continues, “The tannery is a really good example because of the legacies of colonialism and capitalism in this space, and how consequential each piece is to the other.”

On a map of the planet, the Davis Tannery is a tiny pinpoint. But it is a site of immense importance because it embodies such a wide spectrum of distinct struggles. It can feel overwhelming to parse through the site’s complexities, but that’s not a reason to avoid addressing them. “We’re not being called upon to solve,” says Milloy. “We’re being called upon to respond.”

Just as there’s no neat and tidy solution to global ills like climate change and economic inequality, there’s likely no silver bullet that will fix the problems of the Davis Tannery or scores of other hot spots across the country. But one thing is indisputable: failing to confront the ghosts of the past with a more just and ethical world in mind risks creating new ghosts for the future. The Davis Tannery can be a turning point or a point of no return.

The battle rages on. Meanwhile, the turtles lie dormant, hibernating in the riverbed while waterfowl go about their business along the shoreline. The rabbits and squirrels scamper through the bullrushes and around the trunk of the great white oak as it groans and creaks in the raw December wind, as if it’s trying to say something.

***

Luke Ottenhof is a writer in Kingston, Ont. This story first appeared in Broadview’s April/May 2022 issue with the title ”Wetlands vs. developers.”

This essay is over-the-top masterful. Would you kindly tell me how/where I can get a printable copy with all of its photos still in place in the text?

Hi Dugald,

You can find it in our April/May 2022 issue. You can buy a PDF copy of that magazine here: https://broadviewmagazine.myshopify.com/products/april-may-2022-pdf

Oh Wow. Thanks much for your very quick reply. I shall buy my own PDF copy right now and put it to good use tomorrow at 1000.