The Chowkidar recognized my mother as she stepped out of the car. He certainly had not seen her in a quarter century, perhaps as long as 40 years, but the sentry leapt from his post and rushed over to us. It was 1994, and we had just driven two hours directly north from Lahore on a national highway through the verdant and dense Punjab landscape. He greeted her warmly and begged us to wait at the gates to the seminary. Then he yelled at a boy to go inside and tell the principal that Miss Vazir Chand had arrived.

Seven decades earlier, my mother, Joyce, was born here at the Gujranwala Theological Seminary, where her father had once been the principal. The youngest of six children, she had grown up on this campus until her late teens, when she left for university and then teacher’s college in Lahore, Pakistan’s second-largest city. She told me the sentry was a bit older than her and that she remembered him. In fact, he had taken over the post from his own father.

You may unsubscribe from any of our newsletters at any time.

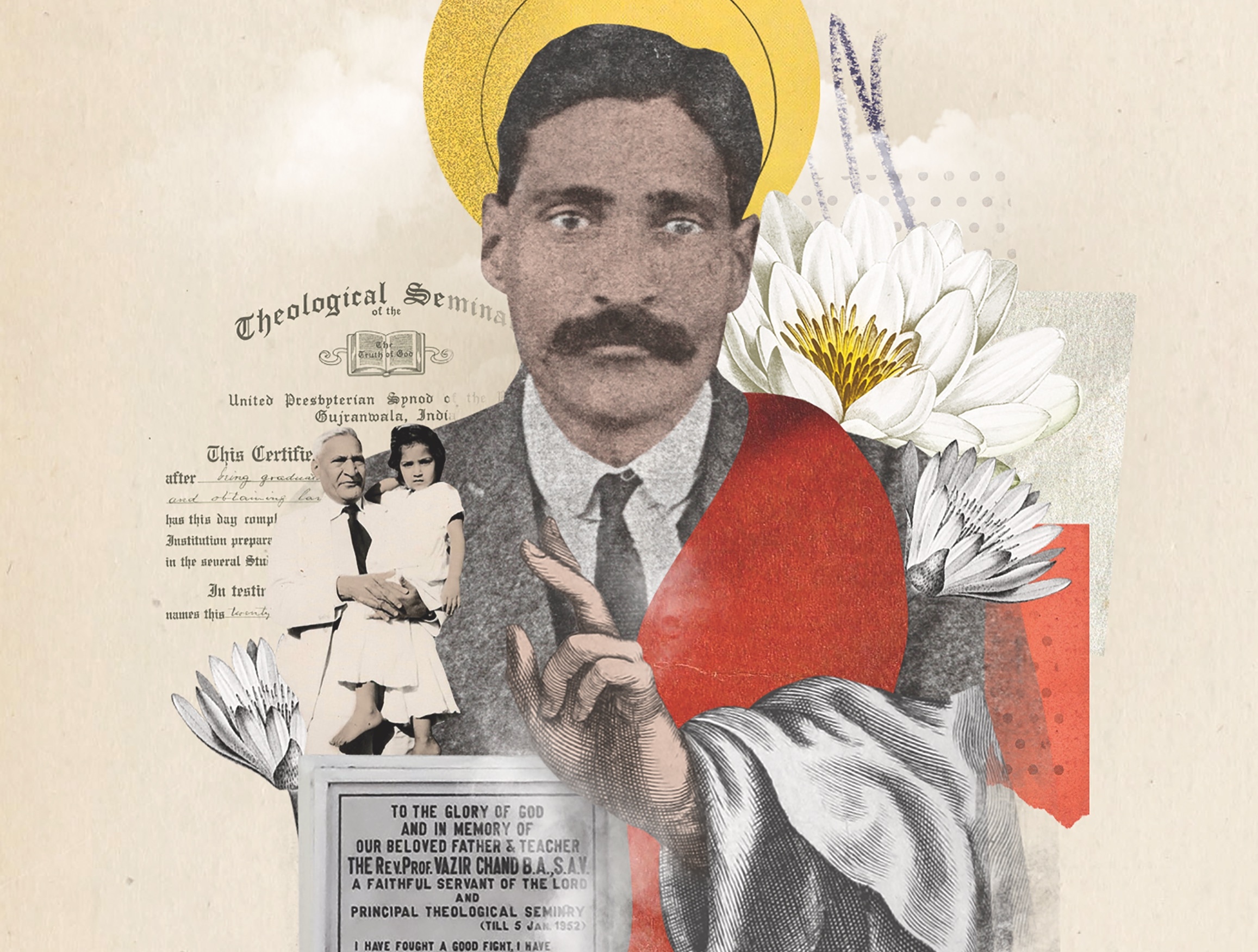

This seminary was founded by the United Presbyterian Church of North America in 1877. Walking along the boundary walls that day, I found an embedded marble plaque. I called to my mother. She read it and began to cry: St. Vazir Chand. Her father. That’s why, upon our arrival, we were asked to wait. She wasn’t just another person from the olden days dropping in for a nostalgia visit. The daughter of a saint had to be received formally.

More on Broadview:

- Sister Thea emboldened me to take on racism among my fellow Catholics

- Dear St. Teresa of Ávila, I love you but some of your ideas are nonsense

- How I learned to embrace St. Anne like my high-waisted mom jeans

My maternal grandfather was born in 1881. His father, Lal Chand, converted to Christianity, and a U.S. missionary mentored him to be an evangelist in the Punjab area, which was part of India at the time. By 1905, at the age of 24, Vazir Chand received a bachelor of arts, and then a certificate to become a teacher. By 1928, when he joined the Gujranwala Theological Seminary as a professor, he was an experienced teacher and parish minister. He eventually became the first Indian-born head of the seminary.

Vazir Chand died in 1952, almost a decade before I was born. Since then, the community he served deemed him a saint, not in any official capacity, but as an honorific for their first native leader. In an autobiographical letter, he wrote that the “story of my life…is a story of how God has directed my affairs in life according to His own plans.” Unlike Catholic saints, there are no miracles associated with my grandfather, other than doing well, being there and serving a long time.

My grandfather’s populist canonization is best understood as a reflection of Pakistan’s culture in which religious identity matters. The country was born out of religious strife. In 1947, British India was split into two countries: Muslims went one way, Hindus and Sikhs another, and during that partition, as many as two million people were murdered, some brutally, some hand to hand, Hindus by Muslims, Muslims by Hindus, along with others who got caught in the middle. This meant Vazir Chand was born in India and died in Pakistan. Through him, the community of half a million Pakistani Presbyterians declared: we can stand on our own.

Perhaps Vazir Chand is in my bones. I’ve never felt so. Immigration severed my connection to the past.

I experienced the significance of this declaration again in 2016. I was an editor with the now-defunct Presbyterian Record magazine, and I was invited to a visit with leaders from the Presbyterian Church of Pakistan at the Canadian church’s Toronto head office. At one point, the Pakistani moderator struggled to express an idea, and I, with my limited Urdu, translated it for him. That turned the Pakistanis’ attention to me, and in the ensuing conversation I mentioned my grandfather.

The atmosphere in the room changed. One of the Pakistanis said to me, “You know Padri Vazir Chand is our saint.” I said, “Yes, I remember the plaque when I visited the seminary.” He said, “You have to understand, he is our saint.” He used the Urdu word hamara. Ours. He is ours. Then the visiting Pakistanis asked if they could touch me; by touching me, they would be touching my grandfather. The same thing had happened at the seminary 22 years before. As my mother walked the grounds, I heard whispers, “She’s the daughter of the saint,” and some knelt to the ground to touch the hem of her sari.

Perhaps Vazir Chand is in my bones. I’ve never felt so. Immigration severed my connection to the past. My father, Victor, once told me he hesitated before deciding to come to Canada. His Christian friends had started leaving in the mid-1960s because of the religious tensions aimed at non-Muslims. “In Pakistan, I had a name. I had a history,” he said. “I knew in Canada I would have neither.”

When we arrived in Canada in 1971, we had to start all over again, forge a new name, a new legacy. My family’s histories are exotic or quaint in this country. That’s one of the costs of leaving the land of your birth. Immigration moved me into what I call a meta-colonial state. What I lost in being a Pakistani, I gained in being a Canadian. The agency I have here is different than what I would have had where I was born. My father knew that, and in my seventh decade I understand his wisdom. Still, it is nice to know, I suppose, that if my daughter ever wants a great cup of tea and delicious sweets, all she has to do is wait outside a seminary in Gujranwala, Pakistan.

***

Andrew Faiz is an associate editor at Broadview.

This story first appeared in the July/August 2021 issue of Broadview with the title “My grandfather, the saint.”

An incredible legacy of a great and humble saint!