Joey Brackenbury wasn’t expecting to debate a priest when he showed up to his Grade 8 classroom in Perth, Ont. It was 2007, Brackenbury was 13, and the clergyman was delivering a lecture to the room of pubescent teens as the class’s teacher looked on.

The talk took a turn when the priest suggested that same-sex attraction isn’t wrong but acting upon it is (a recurring tenet of the Catholic stance on queerness). Brackenbury, who has a queer aunt and would come out himself a year later, felt obligated to raise his hand. “I don’t think that’s true, what you’re saying,” he remembers telling the priest.

You may unsubscribe from any of our newsletters at any time.

The two had a tense back and forth, and when the priest refused to budge on his views, Brackenbury left the classroom. His teacher followed. “She was basically saying, ‘I’m on your side and I agree,’ but she was also still trying to justify what the priest was saying,” says Brackenbury, who is now 26. “I felt [that] happened because it was a Catholic school specifically and not a public school.”

Brackenbury’s dad, Phill, couldn’t agree more. He’s currently teaching Grade 4/5 at the same Perth school that Joey attended, and has worked in Ontario’s separate school system for over two decades. “From the day I started teaching in the Catholic board, I’ve always had some discomfort,” says Phill, citing his progressive social values that sometimes conflict with the Catholic values he’s required to teach.

He says he’s often defied Catholic tradition by teaching his young students about queer people, using his son as an example of how gay people can be themselves and lead happy, healthy lives. “I was working on the inside to undermine the Catholic hierarchy,” he says, then reconsiders, comparing the immensity of the Catholic Church to his small classroom. “But I can’t give myself that kind of credit.”

Thinking of his son and other queer kids who faced adversity in Catholic schools, Phill begins to tear up. A lot of Catholic kids “certainly grew up in a cone of silence about sexuality or their gender identification,” he says. “That’s what’s always bothered me about my job.…For many reasons, I would actually welcome the ending of the Catholic school board.”

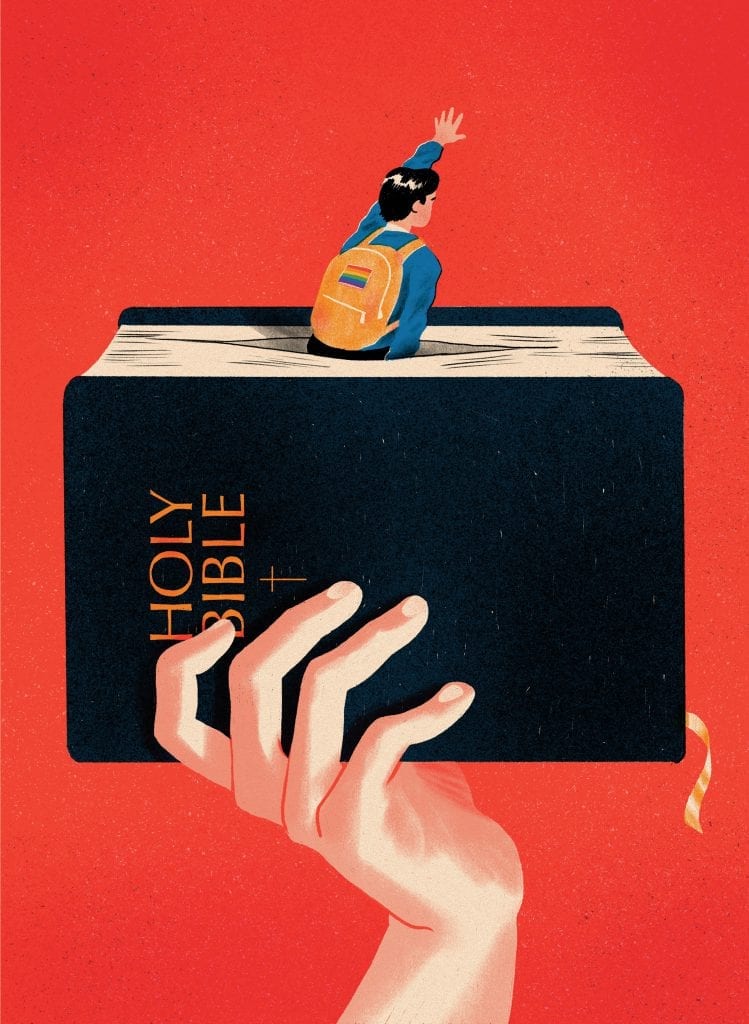

The obstacles faced by queer staff and students in Ontario’s publicly funded separate schools are multi-layered. An outdated sex-ed curriculum and a general lack of supports for queer people in all of the province’s schools have long been big issues. But in Catholic schools, these pitfalls are exacerbated by a religious doctrine that condemns homosexuality.

There has been some progress in the past few years, including an expanded provincial sex-ed curriculum, LGBTQ2-affirming policy decisions and increasing acceptance for the queer community. Recently surfaced comments by Pope Francis expressing support for same-sex civil unions are another hopeful sign, though the impact on official church policy is hard to predict. As things stand, academic research and anecdotal evidence suggest that those who are LGBTQ2 are still at greater risk of alienation and discrimination in Catholic educational environments than in secular ones. This is leading some advocates to join the call for the defunding of separate schools altogether.

Catholic schools in Canada have a long history. The idea of public funding of denominational schools is entrenched in the Constitution Act of 1867. Its 93rd section states that individual provincial governments have the unilateral power to fund (or not fund) “separate” Protestant and Catholic school systems.

Only six of the 10 provinces (and two of the territories) opted to fund separate school systems. Three of those eventually defunded theirs — Manitoba in 1890, then Quebec and Newfoundland and Labrador 100 years later. Only Ontario, Saskatchewan, Alberta, Yukon and the Northwest Territories continue to uphold government-funded separate school systems. (This does not include the church-run residential schools for Indigenous children.)

Currently, of the more than 4,800 publicly funded elementary and secondary schools in Ontario, over 1,500 are Catholic. And of the province’s two million students, about 670,000 attend separate schools. Catholic schools follow the Ministry of Education’s curricula just like secular schools — the difference is that the students must take additional religion courses. But for Catholic school graduates like Jena Kaplaniak, official curricula don’t reflect what’s actually going on in many classrooms.

Kaplaniak, 21, says LGBTQ2 issues were a taboo subject in her Grimsby, Ont., Catholic high school — queer people were scarcely spoken of, if they were mentioned at all. Grimsby is a longtime Tory stronghold nestled on the highway between Hamilton and Niagara Falls, Ont. Growing up queer in a conservative town of less than 30,000 people was a steep enough hill for Kaplaniak. She says attending the only Catholic high school made matters worse. “I remember being 15, and it was like, ‘I am straight, 100 percent,’” Kaplaniak says. “I think that’s from growing up in that silence.”

Kaplaniak didn’t come out until the day of her high school graduation in 2016. Had she gone to a public school, she believes that would have happened much sooner. She says the erasure of queer topics made her feel ostracized and isolated in her school. “Just to [have known] that there was anybody there would have been the biggest difference,” she says.

More on Broadview:

- Inside the fight for LGBTQ2 inclusion in evangelical churches

- The United Church-led fight against conversion therapy

- The West can’t lay claim to LGBTQ2 acceptance

As of 2019, all Ontario students had LGBTQ2 topics rolled into their health classes. For example, students learn about sexual orientation in Grade 5 and gender identity in Grade 8. However, the Assembly of Catholic Bishops of Ontario negotiated a loophole with the provincial Ministry of Education: separate school teachers are allowed to filter certain teachings through a Catholic lens.

Although Catholic trustees and school staff could easily interpret this leeway as an opportunity to ignore or even disavow the LGBTQ2 community, the Ontario English Catholic Teachers’ Association (OECTA) says this is not the case. OECTA, which advocates for Catholic teachers in the province, has made statements affirming that members of the LGBTQ2 community should be supported. “While there is undoubtedly progress still to be made in the Catholic education community with respect to LGBTQSI+ issues, OECTA is proud of the role we have played in changing attitudes and advancing rights,” OECTA president Liz Stuart said in an email.

Christopher Campbell’s research suggests, however, that efforts like these haven’t gone far enough. Campbell is the research program co-ordinator for the University of Winnipeg’s RISE (Respectful, Inclusive, Safe and Equitable) schools project, an initiative aimed at making schools safer and more inclusive for queer youth. Campbell worked on the Every Teacher Project, a large-scale study published in 2015 that surveyed educators from across Canada about the state of LGBTQ2 inclusion, information and acceptance in schools.

The survey revealed some alarming statistics: just 57 percent of Catholic school educators said they would be comfortable discussing LGBTQ2 topics with students, while nearly three-quarters of secular school educators said the same. Catholic school teachers also reported a greater fear of being fired for discussing LGBTQ2 issues with students compared with public school teachers.

In addition, the study found that Catholic educators were 12 percent more likely than their secular counterparts to have knowledge of LGBTQ2 students engaging in self-harm. More than half of respondents from Catholic schools knew of queer students switching schools for safety reasons. By contrast, just 38 percent of secular school respondents said the same. “Generally, schools are not safe for LGBTQ students,” says Campbell. “There are significant differences between what’s going on in Catholic schools and what’s going on in non-Catholic schools.”

Tonya Callaghan, an associate professor at the University of Calgary, echoes these concerns over safety. Callaghan’s research focuses primarily on the systemic mistreatment of queer people in Canadian Catholic schools. In fact, she wrote the book on it: Homophobia in the Hallways: Heterosexism and Transphobia in Canadian Catholic Schools. Published in 2018, it documents painful stories of Catholic school staff and students who identify as members of the LGBTQ2 community. “There’s a Catholic stance on what they call homosexuality,” explains Callaghan. “It’s okay if you’re going to identify as a gay person, but you’re supposed to be celibate.”

Her research was inspired by her work as an English teacher in a Calgary Catholic high school. In 2004, one of her openly gay students died by suicide after months of homophobic bullying. She found out after his death that he had approached the school’s counselling services for help. They told him to “tone down the gay” if he wanted to avoid being bullied. “Catholics are known for liberation theology and trying to help the poor. But they’re not good at other social justice issues, for example gender and sexuality,” says Callaghan. “They get a huge failing grade on that.”

For Callaghan, the path ahead is clear: revoke the public funding of Catholic schools. “There’s a reason we have the separation of church and state,” she says. “It’s just not good for a healthy democracy to have separate faith-based schools. No one will be able to understand one another if they’re constantly in their own little silo, swimming in the same ideas that have been circulating for a century.”

During her career at the Hamilton-Wentworth Catholic District School Board in southern Ontario, Jackie Bajus did her best to introduce new ideas and a better understanding of LGBTQ2 issues. Retired since 2014, Bajus worked at the southern Ontario board for nearly five decades, eventually becoming superintendent.

She says it was common knowledge that staff weren’t supposed to “rock the boat” on LGBTQ2 issues. “More and more people were talking about the whole LGBTQ situation, but it was still a no-discussion point within the board,” she says. “They hid it under a rock.”

However, social workers would come to her often, desperately seeking help to support a growing number of openly queer students who felt isolated and unsafe in Bajus’s schools. “Some of these young people were doing self-harm or thinking suicidal thoughts,” she says.

So Bajus decided to lift the rock. She booked a meeting with the board’s top bosses about the experience for queer students, and they began a series of difficult, emotional conversations. After working through a number of differences and several bureaucratic roadblocks, those meetings eventually resulted in concrete action, including the creation of gender-neutral bathrooms in some schools in 2014 to accommodate trans and gender non-conforming students. That decision was seismic for Bajus, who took it as a sign that progress is possible, however incremental it might be. “It takes a lot of work, but it can be done with the right attitude from the top down.”

Not all boards share Bajus’s attitude, though. The Toronto Star reported in 2019 that the proposed protection of “gender expression, gender identity, family status and marital status” from discrimination in the Toronto Catholic District School Board (TCDSB) code of conduct sparked an internal firestorm and a petition war. These are protections offered by the Ontario Human Rights Code and the Ministry of Education, but a subcommittee of the TCDSB, Canada’s largest Catholic school board, voted to keep gender expression and identity out of the official policy. After months of debate and a marathon meeting, however, the board did include the gender protections.

Catholic boards must also adhere to Ontario’s Accepting Schools Act, which passed in 2012. It guarantees students the right to establish and maintain LGBTQ2-affirming clubs like gay-straight alliances (GSAs) in any school, public or separate. For 22-year-old Ben Kwashigah, the new law presented an opportunity. After taking a leadership role with the GSA at his Oakville, Ont., Catholic school in 2015, he was hopeful about carving out a safe space for himself and other queer students.

His school seemed progressive enough in terms of LGBTQ2 issues — he learned about gender identity and sexual orientation in his Grade 9 health class, and a couple of teachers agreed to be GSA staff supervisors. But homophobic microaggressions began to percolate around Kwashigah and his club members.

GSA posters were pasted to students’ lockers in cruel attempts to pejoratively paint them as being queer. When Kwashigah and the other GSA members tried to get teachers to wear pins in solidarity with the LGBTQ2 community, they refused. Despite some support from the school, Kwashigah says dismissive and ignorant attitudes toward queer people hindered the club’s ability to thrive. “It wasn’t something that was accepted,” he says. “It felt like it was just tolerated.”

“It’s just not good for a healthy democracy to have separate faith-based schools.”

Tonya Callaghan

According to Renton Patterson, experiences like Kwashigah’s are still all too common in separate boards. Patterson is the president of Civil Rights in Public Education (CRIPE), a group that seeks to inform people about what he describes as discriminatory practices happening in Catholic schools. Besides the treatment of LGBTQ2 staff and students, Patterson points out that publicly funded Catholic schools reserve the right to hire only practising Catholics as teachers. Patterson, who taught in a high school in Pembroke, Ont., is not Catholic, and would therefore be disqualified from working at a Catholic school. “The government is using my money to discriminate against me,” he says.

CRIPE is calling for the defunding of Catholic schools — a sentiment that is gaining traction. According to a 2018 Ipsos poll, 56 percent of respondents support the amalgamation of Ontario schools. “It’s an economic disaster and a social disgrace for public money to go into the Roman Catholic school system,” says Patterson. “There’s absolutely no social benefit, no benefit to the public, no benefit to Ontario whatsoever.”

Reva Landau agrees with Patterson and is prepared to take the province to court. Landau is a co-founder of One Public Education Now (OPEN), another organization seeking the end of public funding for Ontario Catholic schools, although OPEN is not using the treatment of LGBTQ2 youth as an argument in its legal challenge.

“We don’t like to get into whether there are any specific practices or philosophies of Catholic schools [motivating our call for defunding],” says Landau. Such arguments only prompt Catholic schools to update their policies “just enough so they get over that barrier,” she says, citing the protection of gay-straight alliances and other LGBTQ2 clubs. “What we want to get into is the general principle that one religion should not be supported when [Canada is] supposed to be a multicultural, equal-opportunity country.”

OPEN is organizing a legal argument that seeks to rectify what it sees as an unfair favouring of Catholic schools. After filing freedom of information requests, OPEN says Catholic schools in Ontario receive about $1,620 more per student than public ones. “Either everybody should be funded equally,” says Landau, “or you should only have a public school system.”

In an email, Ingrid Anderson, a spokesperson for the Ontario Ministry of Education, confirms that English Catholic schools do receive, on average, more funding per pupil from the government of Ontario than English public schools, although French public schools receive more than French Catholic schools. “Cost structures vary from school board to school board, the average funding per student varies across boards,” writes Anderson. (At the time of publication, the Ministry of Education had not responded to questions about why this disparity exists.)

OPEN also claims closing the separate school board could save the province up to $1.6 billion. By contrast, a Catholic school promotional document, “168 Years of Success: Ontario’s Catholic Schools, An integral part of publicly funded education,” claims that creating a single school system will cost more time and money, not to mention “it would also unleash a period of great upheaval for students, parents, teachers and administration throughout the education system.”

Although she understands first-hand how tough it is to make Catholic schools safe for queer kids, retired Catholic board superintendent Jackie Bajus also doesn’t mince words when it comes to defunding them: “It would be a horrible mistake.” She believes Catholic schools are necessary because they provide a faith-based alternative to secular schools, which appeals to parents of all religious backgrounds.

Bajus acknowledges that some staff members still hold biases and says they need to remember Catholic schools are fundamentally inclusive. “One of the first big pillars that we have to keep in mind is that God created everyone equal. We are all his children and that’s the message that we in our Catholic schools continually give.”

Despite Joey Brackenbury’s negative middle-school experience, he and his partner — who still live in Perth — have surprising plans. “I know this is [ironic],” he begins, “but when we discuss having kids, and we discuss which school we’ll send them to, we actually have discussed sending them to the Catholic school in town.” That’s the same school where Joey and the priest exchanged verbal volleys all those years ago.

Defunding Catholic schools isn’t on Brackenbury’s radar — he just wants the best possible education for his future children. He believes the Catholic school could provide that, but he is nervous about what that might mean for his family. “A lot of what they could end up learning at Catholic school would fly right in the face of our kids’ dads,” he concedes.

It’s clear that Brackenbury and his partner are on the fence about Catholic schools. They realize institutions are notoriously tough to change, nevermind overthrow. Even the Pope’s recent endorsement of same-sex civil unions is no guarantee of a meaningful shift in church doctrine. “The problem with the Catholic Church is they don’t update their stances on things,” he says. “It would be a little naive of me to think that things will be different in five to six years when our kid is going to school.”

CORRECTION (Jan. 12, 2021): A previous version of this article incorrectly stated that no territories fund separate schools, when Yukon and the Northwest Territories do fund Catholic schools. This version has been corrected.

A version of this feature appeared in Broadview’s January/February 2021 issue with the title “The trouble with Catholic schools.”

KC Hoard is a writer in Toronto.

I tend to think that all faith based schools (including Roman Catholic) should not have funding (but perhaps some percentage of their taxes for education reallocated back to them). This seems to be a healthy middle ground (I’m writing as someone who is from Ontario so my comments apply to Ontario only):

1. Respects all faiths by not elevating one faith group (RC) to a status above all others;

2. Since Ontario’s public education is no longer effectively Protestant, there is no reason to uphold the original 1867 argument for funding;

3. Allowing people who don’t have a belief system or who are from another faith to not have to support one particular faith group (RC);

4. To provide a limited amount of refunding to any faith group or other minority group, so that the majority (public system’s secular education) does not impose its will on the minority;

5. To provide a reasonable amount of tax base for the public system to support secular based values and education system.

I educated my children mostly in a private faith based system (non RC) and didn’t mind having most of my money go to the public system. My reasons were primarily because the level of education I judged was better. However, I did see a problem with having one faith group (RC) have their entire tax educational amount go to their faith based education. I think this is the only philosophically fair way in a pluralistic society to deal with differences. Otherwise their will be some type of discrimination in favor of one faith or other type of group (including if it favors the public system which also has a particular view point on social, cultural and personal issues).

The priest had every right to be there in that classroom speaking on church teaching and the LBGTQ youth had every right to leave. Part of me says just take another option and go to a public school where this issue will not play out the same way. However, one must also realize that in many schools discipline is nonexistent and a LBGTQ youth might find that he or she is caught up in a situation where rules are not enforced so it is open season on them or anyone else the class bully decides to target. Another part of me says yes it is long past time for the province of Ontario to defund Catholic schools because Catholic teaching means absolutely nothing to those teaching or attending them.. Given the state of Ontario’s finances, it is probably this option that I support as a cost saving measure.

Thank you very much for covering this issue. It is a serious concern for so many students who attend Catholic schools and their teachers. As a young girl in a Catholic school, I was very troubled by the response from our teacher when asked why girls could not be priests. I could tell at about age 9 that she did not really believe the answer she gave us – that Jesus (and so God) chose only men for that role. I remain very concerned for girls who are growing up in a school system they are often told is superior to the Public system. They are told their teachers care more and that the moral teaching is superior in their Catholic school and behaviour is more considerate. If they take their religious education seriously it will trouble them for a long time. To experience misogyny wrapped in language of love and care is devastating. I am so grateful my parents allowed me to go to a public high school in grade 10 (many years ago). I am grateful I have found the United Church.

I look forward to the day Catholic schools are no longer funded in Ontario.