As told to Raizel Robin

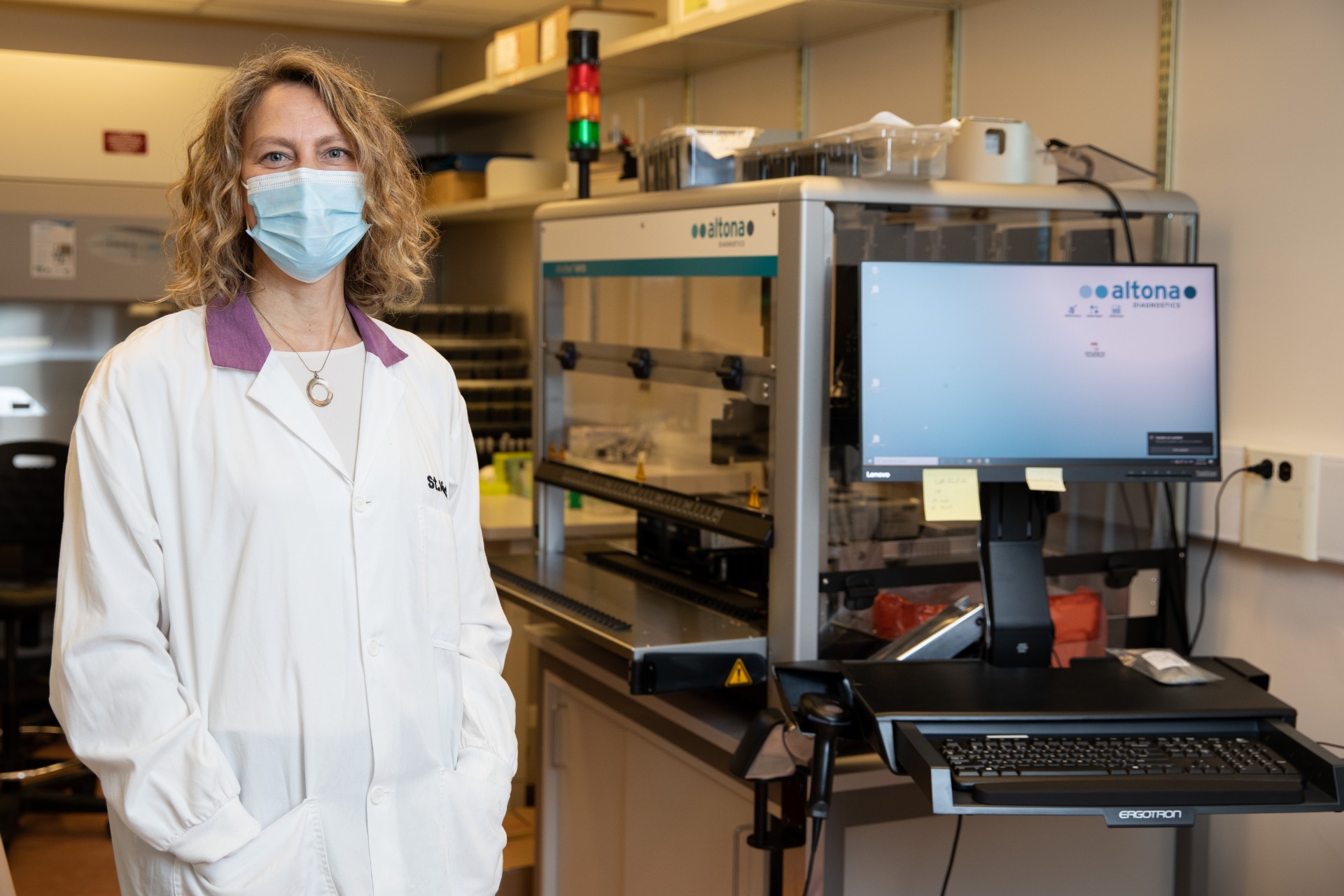

I’m head of microbiology and biosafety for St. Michael’s Hospital and Unity Health, a network of Catholic hospitals in Toronto. It’s my job to help us prepare and implement testing for COVID-19. My days are always busy but now more than ever.

You may unsubscribe from any of our newsletters at any time.

On a typical day during COVID, I wake up and make breakfast for my kids — they’re seven, 12 and 16. I’ll cut up some fruit, put out some yogurt drinks and the like. I used to just get up and go to work, but I’m finding now that my days are long, sometimes 15 hours, and I’m generally home late in the evening. Sometimes I work weekends as well. So I ensure that we eat together as often as possible and cherish our family time together.

At work, I spend some time checking on the labs I oversee but most of my day is in meetings. As a specialist in infectious disease and rapid diagnostics, I’m at meetings across the province — via videoconference, of course. My focus right now is getting the fastest turnaround time for test results. The faster we know if somebody is infected or not, the quicker we can act. It has a huge impact on how we manage the patient and on what types of precautions health-care workers need to use, including what personal protective equipment we should wear.

More on Broadview: How nearly dying prepared me for isolation

When a new infectious disease appears, scientists must first identify the pathogen and then they can develop a test to detect it. We have come a long way in medical diagnostics over the past 20 years. The time it took to identify the organism COVID-19 was so quick. It was unprecedented. Now we have a flood of tests coming on the market. We need to know how good they are at detecting who is truly infected, and which tests missed disease — in other words, how accurate and reliable they are. Ideally, we do a big population study to figure this out. But we don’t have the luxury of time to do those big studies.

Seventeen years ago, I was a resident infectious disease specialist on the front lines during SARS. I consulted with doctors to help them diagnose and detect the disease, and to see and manage patients. COVID-19 is worse than SARS was. It has spread more broadly and killed more people. Also, people might be spreading it before they have symptoms.

Like SARS, we don’t have a vaccine or treatment for this disease. The only way to stop it is to isolate infected people — whether that means keeping them quarantined at home or in isolation rooms in the hospital. Widespread testing is critical for this — it’s how we identify and contain it.

But we don’t have the ability to do widespread testing just yet. The whole world needs testing — right now. Diagnostic testing for infectious diseases is a niche market. Not everyone makes those tests and not everyone can interpret them. You need skilled people to perform and analyze the tests. And no place in the world has the same infectious disease at the same time. The flu, for example, starts in the Southern hemisphere and moves to the Northern hemisphere.

We need more experts; we need more lab professionals; we need more labs.

The test manufacturers don’t keep the amount of supplies and reagents to do the scale of testing we need right now. That’s why manufacturers and vendors haven’t been able to meet the current demand. Making lab tests isn’t like making hand sanitizer. You can’t ask your local ketchup factory to flip a switch and start making medical products. Manufacturers need to adhere to strict regulatory requirements. The people qualified to analyze test results are hard to come by, too. There are many factors at play.

A major factor is the lack of hospitals that have onsite microbiology labs. Many hospitals don’t have them or the experts needed to staff them. These labs have been shut down and consolidated over the past several years by the government, which limits access to lab testing. Not only that, we have witnessed a dwindling pool of medical lab techs and microbiology experts. They are the experts who figure out how to test accurately and quickly, so they play a vital role in addressing outbreaks and pandemics. We need more experts; we need more lab professionals; we need more labs.

The big question is: when will we have the capability to do widespread testing in Canada? I don’t know the answer. But if we reopen the country before we have that capability, COVID-19 will continue to spread like wildfire.

I stay as optimistic as possible. During SARS, I remember anxiously calling my mentor. I was walking into the hospital one cold morning and I was overcome with fear of the unknown and the weight of the responsibility I was carrying. I had never experienced an epidemic so devastating before. Neither had many of my colleagues. One sentence was all that it took to lift the burden: “All outbreaks burn themselves out.”

This one will, too. There is always a light at the end of the tunnel. It may be a long and dark tunnel, but we’ll get to the other side. We did then and we will again.

Broadview is an award-winning progressive Christian magazine, featuring stories about spirituality, justice and ethical living. For more of our content, subscribe to the magazine today.