WASHINGTON (RNS) — The worship service began with the sound of Beyoncé singing “Lift Every Voice and Sing,” a song also known as the “black national anthem.”

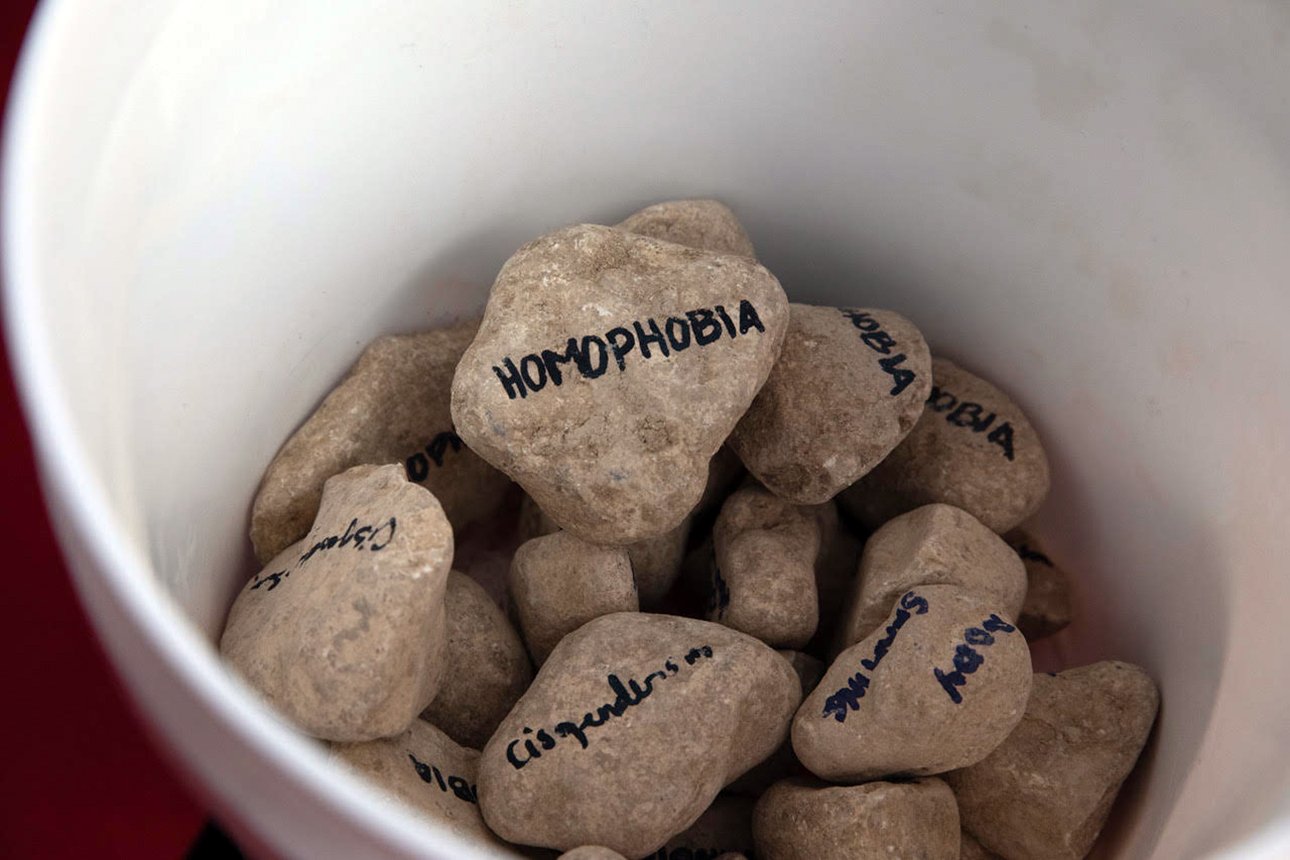

Over the next hour, a choir-backed quintet of black women singers belted out other songs in the pop star’s repertoire. Beyoncé’s music filled the air between prayers, a sermon and a Communion-like time when congregants dropped rocks labelled “homophobia,” “body shaming” and “racism” into white plastic buckets that were placed before an onstage altar.

You may unsubscribe from any of our newsletters at any time.

On Sunday (March 8), International Women’s Day, a theatre in the Kennedy Center was turned into the latest sacred space for Beyoncé Mass.

After the singers in the Black Girl Magic Ensemble sang “Survivor” — a song from Beyoncé’s days as a member of Destiny’s Child — Rev. Yolanda Norton greeted the crowd of more than 500 people.

“We don’t do frozen chosen here; this is not your grandma’s church,” she said, wearing a purple “Won’t SHE do it?!” T-shirt on the Eisenhower Theater stage. “Sing as loud as you can, dance, clap, love, live, understand this worship: You are welcome here.”

Norton, 37, created the womanist worship service after she gave her Hebrew Bible students at San Francisco Theological Seminary an assignment to tell black women’s stories using Beyoncé’s music in a worship setting. She then developed a full liturgy that was presented at her seminary’s chapel, and later at an event that drew about 1,000 people to San Francisco’s Grace Cathedral in 2018.

“We are not worshipping Beyoncé,” Norton said, twice repeating her answer to an oft-asked question. “It is a Christian worship service and we are focused on the mission movement of Christ in the world and we are trying to promote a gospel message of love, inclusion and justice.”

Norton discovered that people beyond her seminary were interested in the service that combines worship and women’s rights.

“Because of the response that we got in San Francisco, we have accepted invitations to go various places across the world to do the mass,” she said in an interview.

Beyoncé Mass has been presented, in partnership with churches and religious educational institutions, 10 times, including in New York, in Portugal and in early March as the kickoff to “Women’s Herstory Month” at the chapel of Spelman College, a historically black women’s school in Atlanta. In Washington, as elsewhere, it attracted a predominantly black female crowd but included people of a variety of ages, races and gender identities.

Norton said Beyoncé’s music is fitting for a service that focuses on womanist theology, the intersection of gender, class and race and the empowerment of the marginalized across the African diaspora.

“It represents something about the kind of stories that black women encounter in the world all the time,” said Norton. “In her music we see her as mother, we see her as mourner, we see her as wife, we see her as activist, a person struggling with their own body image and identity.”

After the ensemble sang a portion of Beyoncé’s “Heaven,” male and female worship leaders took turns reading names of black women, including Sandra Bland and Atatiana Jefferson, who had died as a result of police actions. Later, after the singing of “I Was Here,” a video played featuring women telling their stories of being among the first in their career fields and desiring to improve society for others.

Through a song like “Flaws and All,” a staple of Beyoncé Mass wherever it has been held, Norton said, the singer’s music can be sung as a prayer by women facing a range of emotions as they encounter God.

“The chorus of the song is, ‘I don’t know why you love me and that’s why I love you,’” said the Christian Church (Disciples of Christ) minister. “I don’t know about anybody else but that tends to be my refrain with God: I’m not quite sure why God loves me, but I really do love God.”

Dean Emilie Townes of Vanderbilt University Divinity School said Norton has used Beyoncé’s music to create a service that empowers the spiritual journeys of black women but also “is stirring, it is thoughtful, it is liberating, it is a holy mass that can free us all.”

“In her music we see her as mother, we see her as mourner, we see her as wife, we see her as activist, a person struggling with their own body image and identity.”

Others have been less affirming of the liturgical use of Beyoncé’s music in a service that includes a “Womanist Lord’s Prayer” that begins with the words “Our Mother, who is in heaven and within us, We call upon your names.” After the event at the Episcopal cathedral in San Francisco, author David Fiorazo wrote that “doing this at a church was both confusing and controversial.” Juicy Ecumenism blogger Jeffrey Walton called that same service “predictably over-the-top.”

Rev. Wil Gafney of Brite Divinity School, who noted that the secular and the sacred have always coexisted in church settings, said Beyoncé Mass seems to have raised more eyebrows than did the U2charist services that were popular among young Episcopalians in the early 2000s.

“I didn’t see or hear the accusation that people were worshipping U2 or quite the volume of ‘is this appropriate’ questions,” said Gafney, a professor of Hebrew Bible. “Black women are subject to a compounding of sexism and racism; that is why the Beyoncé Mass is received so differently than was the U2charist.”

Beyoncé, who has described St. John’s United Methodist Church in Houston as her “home,” has been known to represent a wide array of religious experiences. She sang “Ave Maria” on her 2008 I Am … Sasha Fierce album. She evoked Divine Mother imagery from various religious traditions during her 2017 Grammys performance. And, in February, she was backed by a choir dressed in white as she sang “XO” and “Halo” at the memorial service for Kobe Bryant and his daughter Gianna.

Just as there is an eclectic range in how Beyoncé has expressed religious themes in her music and performances, an array of people stood in line — some for two hours — to get the free tickets to the Millennium Stage performance that was part of the Kennedy Center’s two-week Direct Current programming focused on contemporary culture.

Marjorie Sims, a black woman from Washington who is a Zen Buddhist and a Beyoncé fan, was among those in line curious about how a theologian would view Beyoncé’s music from a religious perspective.

“I thought that it was a nice blend of the right combination of Beyoncé songs and the message, and I just appreciated the message around the Scripture focused on Esther,” said Sims, 60, a managing director at a Washington think tank. “Because Beyoncé has such a diverse kind of range of songs, I think they all really worked. They were all the right kind of spiritual ones.”

Johanna Lemieux, a white woman from Springfield, Virginia, who was raised Catholic but is no longer a churchgoer, was so excited about the event that she bought two T-shirts and a bag emblazoned with the same “Won’t SHE do it?!”phrase that was worn by the leaders onstage.

“I’m not a churchgoing person and that was a message for everybody,” said Lemieux, 37, an information technology staffer at a small financial firm. “It was very welcoming. It was very inclusive. It speaks to everybody and I feel like that’s a really important message.”

Every Beyoncé Mass is a little different. This one, due to coronavirus concerns, did not have its usual Communion service. It instead featured the rocks, which Norton told participants to use to “lay down the weight of our human failure and walk away with the grace of God.”

Just as she encouraged people to pass the peace in whatever way they felt comfortable — from elbow bumps to bows — Norton concluded by asking the Kennedy Center congregation, rich or poor, churchgoer or not, to keep lifting themselves up along with others.

“We have broken enough in this world. We have done enough harm and damage but I believe, through Christ Jesus, that we can start over,” she said. “Go into the world and do the good thing that God is calling us to. Go in peace and go with God.”