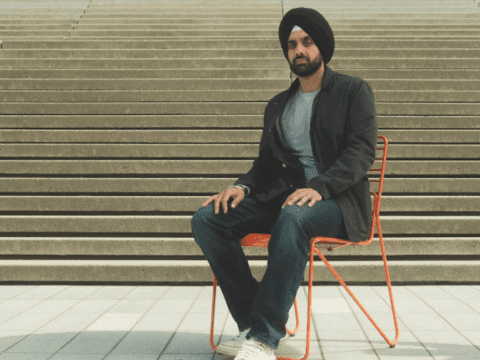

In what could have been the last moments of Steven Kabuye’s life, the Ugandan queer activist proclaimed on X, formerly Twitter, that if he died, it was because he is gay. Kabuye, then 25, was walking near his home in Kampala, Uganda’s capital, on Jan. 3, 2024, when two men surrounded him and stabbed him in the arm and stomach. Before fleeing on a motorbike, the men screamed homophobic remarks at Kabuye, an outspoken defender of gay rights in the country. Stranded on the rust-red earth, unable to reach his friends by phone, he recorded and posted a video on X, pleading for help. “If you can’t [save me], know that this is how I’ve died: the men have killed me for being who I am.”

A colleague saw his video, picked him up and took him to the hospital. But the attack proved to Kabuye that he needed to leave Uganda. Soon after, he arrived as a refugee in Canada — first to Toronto, then Vancouver — with the help of Rainbow Railroad, a Canadian and American organization that helps LGBTQI+ people escape state-sanctioned violence.

You may unsubscribe from any of our newsletters at any time.

Kabuye’s assault occurred just months after Uganda passed the Anti-Homosexuality Act in 2023, one of the world’s most oppressive anti-gay laws. Beyond the existing life sentence for having homosexual sex, the act introduced the death penalty for “aggravated homosexuality,” which is when someone with a terminal illness, HIV or disabilities is involved. It also added a 10-year prison sentence for “attempted homosexuality” and penalties of up to 20 years in prison for those convicted of the “promotion of homosexuality,” which includes LGBTQI+ human rights groups, their financial supporters and even those leasing properties to pro-gay groups.

Local groups reported a rise in hate crimes against LGBTQI+ Ugandans immediately after the act became law, as well as obstacles for people to get testing and treatment for HIV. Devon Matthews, head of programs at Rainbow Railroad, says requests from Ugandans seeking to flee the country more than tripled in the year after the act passed, rising to 1,400 from 400 in 2022.

Uganda’s anti-gay act happened after decades of lobbying from American right-wing evangelical groups, part of a campaign across much of Africa and other parts of the world. An earlier iteration of the law came briefly into force in 2014 until courts annulled it. But that didn’t deter campaigners. Uganda, known as the pearl of Africa for its natural beauty, diverse wildlife and cultural richness, plays a unique role in the evangelical campaign to entrench conservative values in international laws. The country’s young and religious population, turbulent political past and history of missionary-owned infrastructure make it ripe for religious and ideological influence.

More than a year after the attack, Kabuye is adapting to the cold Vancouver air, which he says he can tolerate better than Toronto’s winters. He’s working night shifts at a warehouse and takes college classes during the day, but he’s still deeply involved in gay rights back home. Working remotely for the Kampala-based non-profit Coloured Voices Media Foundation that he helped found, he and his colleagues are petitioning the Ugandan courts to strike down the Anti-Homosexuality Act. We watch ducks swim along a lake in an East Vancouver park, but Kabuye’s mind is on the pearl of Africa. In a country like Uganda, where most people live at or close to the poverty line, “people tend to run to religion for comfort,” he says. “White evangelicals have done much harm to LGBTQ+ Ugandans.”

How did American evangelicals gain so much influence in African politics?

A central tenet of evangelical thinking is the preservation of the nuclear family, says Haley McEwen, a researcher at the University of Gothenburg in Sweden and author of The U.S. Christian Right and Pro-Family Politics in 21st Century Africa, published in 2023. Homosexuality, reproductive rights and abortion are threats to that traditional family system, according to the Christian right. The movement’s “wake-up call,” says McEwen, came in 1995 when the United Nations adopted the Beijing Declaration, the most progressive advancement for women’s rights at the time and a catalyst for gender-based rights. “They realized they needed to be more organized,” she says.

Losing traction at that point on American soil, evangelical groups began looking internationally, playing the long game. Uganda was an ideal place to gain a foothold. The country was faltering after the overthrow in 1979 of dictator Idi Amin; the HIV/AIDS crisis was mounting. Evangelical groups came in to build schools, churches and orphanages, which helped them instil conservative values among the country’s young and religious populations. In the early 2000s, U.S. President George W. Bush mandated that some HIV-prevention funding go through faith-based organizations across Africa. They promoted abstinence instead of condom use. “This ended up funnelling a lot of money into U.S. Christian right groups,” says McEwen. “[It was] the first moment when [they] started to gain a lot of power and influence in U.S. foreign policy.”

Over the past 20 years, U.S. Christian right groups have sent the equivalent of more than C$70 million to Africa, with more than C$28 million coming from the Fellowship Foundation, an evangelical group known for its presence in American political circles, according to a 2020 investigation by openDemocracy. The investigation couldn’t determine how much of the money, if any, originated in federal government funding. In 2009, the foundation’s Ugandan associate, parliamentarian David Bahati, introduced the first version of the Anti-Homosexuality Act — known then as the “kill the gays” bill — under the mentorship of American evangelist Scott Lively, a man connected with several anti-gay groups that link homosexuality with pedophilia. Though the bill was overturned by the courts, anti-gay sentiment in the country remained rampant.

It’s not only Uganda. In recent years, a wave of anti-gay legislation has passed in Africa and Europe, including Ghana, Kenya, Georgia, Hungary and Poland. Christian right groups are lobbying actively around the globe, McEwen says. Their aim is not only religious salvation, but also gaining influence at the United Nations, which sets standards for human rights around the world. When international norms are more conservative, it’s easier to sway local policy to the right.

That influence is already having an effect. In 2020, the United States submitted the Geneva Consensus Declaration — created by Valerie Huber, a White House adviser during the first Trump administration — to the UN General Assembly. Uganda was a co-sponsor. Under the guise of protecting women’s rights and the family unit, the declaration affirms that there is no international right to abortion. It has more than 35 signatories.

In 2021, then-U.S. President Joe Biden withdrew from the declaration. The United States rejoined in the first week of President Donald Trump’s second term.

The conclusion is that queer rights and reproductive rights are intertwined and that lobbyists will go to enormous lengths to see those rights eroded. “The evangelical ethos is that the job isn’t done until you’ve spread the word to every person on Earth,” McEwen says.

It can be easy to blame all anti-gay ideology in places like Uganda on the influence of evangelicals, but that might be giving them too much credit. The legacy of colonialism also plays a role in why these sentiments take root so strongly. According to the U.K.-based non-profit Human Dignity Trust, 65 countries have jurisdictions that criminalize same-sex relationships; almost half once belonged to the British Empire.

Colonial governments used heteronormativity and racial hierarchies to establish power, says McEwen, and anti-gay laws were one way to enforce that. The traditional family model — with women in domestic positions and men working at manual labour jobs — became the standard in colonized places, even though a range of gender and marriage dynamics were practised in pre-colonial and ancient times.

More on Broadview:

At the same time, homophobia is not exclusively a post-colonial issue. “It’s easy to slip into this idea that before colonialism, everything was fine. That there was no male dominance or heteronormativity,” says McEwen. Those did exist. But colonialism just made them the prevailing zeitgeist. And yet while countries like India repealed their colonial-era anti-gay laws years ago, Uganda is still far behind.

The key strategy for U.S. Christian right groups in Africa, according to McEwen, is to connect with existing conservative political and religious figures, then press them on anti-gay and anti-sex-ed agendas. Conferences are key. Shortly before the introduction of Uganda’s first anti-homosexuality act in 2009, for example, evangelicals held an influential three-day seminar in Kampala titled, “Exposing the Truth Behind Homosexuality and the Homosexual Agenda.”

For Kabuye, money plays a role, too. “In a country where corruption dwells, politicians will do anything when money is on the table,” he says.

Rather than trying to find the men who attacked him, Ugandan police tried to arrest Kabuye while he was recovering from his injuries. Nurses stopped them, so they arrested the colleague who rescued him instead. When the colleague refused under questioning to admit that Kabuye is gay, police beat him so brutally that he needed clips in his jaw to reposition it. Kabuye said he would give a statement of his attack in return for his colleague’s release. Police complied, then arrived at the hospital demanding to know who financed Kabuye and how many children he recruited a month.

Kabuye escaped to Kenya the next day, still dangerously ill with high blood pressure. From a hospital in Nairobi, he was able to contact Rainbow Railroad.

He’s still healing emotionally, in part with the help of professional mental health-care experts provided by Rainbow Railroad. Though he’s made friends “who are like family” in Canada, he misses his mother, siblings, closest friends — and Ugandan food. He knows he can’t return to Uganda until LGBTQI+ rights are recognized in the country. In the meantime, he continues his fight from afar. “I never lose hope, unless I’m dead,” he says with a grin. “The future is bright.”

***

Ayesha Habib is a journalist in Toronto. With files from Mzwandile Poncana.

This article first appeared in Broadview’s July/August 2025 issue with the title “Escaping Hate.”