UNRAVELLING THE MYSTERIES OF PRAYER

By Trisha Elliott

Prayer is powerful. No surprise there. The spiritually inclined have been testifying to the power of prayer for millennia. But now science is proving it. For a little over a decade, a growing number of neurotheologians (researchers who study the brain science behind religious and spiritual experience) have brought prayer into the lab. The results are stunning. Not only is prayer proving to be incredibly healthy — right up there with eating right and exercising — it is rewiring our brains. What’s more, the neuroscience behind prayer is reigniting old debates about nature or nurture, exploding dualistic body-versus-spirit theology and sparking controversy over the reality of consciousness.

You may unsubscribe from any of our newsletters at any time.

Andrew Newberg has been studying the neurological effects of prayer and meditation since the late 1990s. The director of research at the Jefferson Myrna Brind Center of Integrative Medicine in Philadelphia, Newberg is the author of several books, including How God Changes Your Brain. His pioneering experiments involve inserting radioactive dye into the brains of both spiritual novices and high-achievers like Franciscan nuns, Buddhist monks and evangelical Christians when they’re hard at prayer.

“The thing that has always been so striking to me is just how rich and diverse spiritual experiences are for people, how they activate so many different parts of the brain,” he says. “There isn’t just one part of the brain that makes us religious or spiritual. If there is a spiritual part of ourselves, it’s our entire brain and how it works when we have these deep experiences, because it seems to be a complex pattern of activity in different directions.”

Newberg reports increased activity in the frontal lobes (the part of the brain that helps focus attention) and, depending on the kind of prayer, increased activity in the language, visualization, emotional and motor centres. The difference between prayer and other activities lies in the ignition. “With religious activity, you seem to engage many other parts of the brain you typically don’t see with simply trying to solve a math problem or driving down the street,” Newberg says. “Prayer creates for the person fundamentally different experiences than any other experiences we have. The distinction comes with the pattern of activity and the intensity of activity.”

While prayer revs up certain parts of the brain, it shuts down others. Several studies show that at the height of prayer, the parietal lobes (the portion of the brain that normally takes our sensory information, orients us in the world and gives us a sense of ourselves) go dark. In other words, when people describe “getting lost” in prayer or “feeling at one with the universe,” that’s exactly what’s happening neurologically. The research has potentially wide consequences. Newberg wonders if losing ourselves in prayer may help us find compassion. “The impact of prayer on violence is an area that hasn’t been studied. But if you get into an existential state where you feel connected to all of humanity, at one with all, then it almost by its very nature has to foster a sense of inclusion and connection,” he speculates.

There’s more good news. Various studies have demonstrated that prayer helps us manage anxiety and depression, boosts the immune system, enhances our capacity to absorb and maintain information, makes us more open to new ideas and increases our pain tolerance. It can even make us less prone to the effects of aging. The longer you meditate, the greater your gyrification (“folding” of the cortex, the part of the brain that helps us process information). These wrinkles are a thing of beauty: the more there are, the better the brain is at making decisions, governing emotions and forming memories.

But what qualifies as prayer? Does our brain expand if we mumble a prayer while washing the dishes, or do we have to sit cross-legged for hours to reap the physiological rewards?

Newberg says it’s complicated. “Not all types of prayer affect the brain in the same way, and these practices are dynamic processes in and of themselves. So let’s say you started out doing the rosary. Well, when you first start doing the rosary, after the first minute or two, your brain is doing something different than if you are doing it after a half hour, an hour or two hours. You can get to a deeper state, a more powerful state . . . even while doing that same exact process.”

No matter the form of prayer, sincerity counts. One study that compared the brain activity of atheists and religious people deep in meditation showed dramatically different activity in the frontal lobes. However, Newberg argues that by contemplating God, non-believers can achieve the same neural benefits as the faithful. “It doesn’t matter if you’re a Christian or a Jew, a Muslim or a Hindu, or an agnostic or an atheist,” he writes in How God Changes Your Brain, co-authored with Mark Waldman.

You don’t have to be the Gretzky of prayer to get results. Neuroscientist Richard Davidson, who teaches at the University of Wisconsin-Madison, wondered if ordinary people could achieve the same results as the spiritually elite. After just two months’ practice, amateurs had “a systematic change in both the brain as well as the immune system in more positive directions,” he told an NPR reporter. The brain is proving to be more flexible than once thought. “You can sculpt your brain just as you’d sculpt your muscles if you went to the gym. Our brains are continuously being sculpted, whether you like it or not, wittingly or unwittingly.”

If prayer can be observed in the brain, can scientists flip the process — stimulating the brain to invokea feeling of prayer? Canadian researcher Michael Persinger, who teaches at Laurentian University in Sudbury, Ont., made waves when he invented what a British tabloid first dubbed the “God Helmet.” The device fits over the head and stimulates the brain’s temporal lobes, generating weak, fluctuating magnetic fields similar in strength to those of a landline phone. Persinger says that 80 percent of people who test drove the helmet experienced a sense of presence, a sentient being in some form. “How they interpreted it varies with their culture. Religious people would say it was God or a deceased member of the family. Atheists would say, ‘It’s in my brain, but I still feel it,’” he reports.

Persinger’s studies have come under fire, particularly from a group of Swedish researchers who say that his experiments are flawed and can’t be duplicated. “The Swedes couldn’t replicate it because they used the wrong kind of computer, they distorted the signal, and despite the fact that we pointed out their technical limitations, this became a really big political hot potato,” he says, adding that his research is a flashpoint in debates between atheists and religious stakeholders. “The truly religious people I’ve met — the priests, imams, Jesuits — they are curious. They say, ‘Let’s find out.’ They are open. But [other believers], if you challenge their belief system, they try to get rid of you,” he says.

Persinger isn’t the only neuroscientist on the frontier whose work challenges traditional notions of spirituality. Neurotheology as a discipline nips at the ankles of a broad spectrum of beliefs, including the traditional notion of free will, mind-matter dualism and the nature of consciousness.

Traditional theology solves the problem of an all-powerful, all-loving God’s decision not to end violence and suffering by chalking it up to free will — in short, God so loves us that God gives us the freedom to choose to destroy ourselves. But how much free choice do we really have when much of what we take in flies beneath our cognitive radar? In Strangers to Ourselves: Discovering the Adaptive Unconscious, for example, Timothy Wilson writes that the human mind registers roughly 11 million pieces of information per second, yet we can only be conscious of about 40. What’s more, our choices may be predictable. In a 2008 study, scientists looking at brain scans were able to predict whether subjects would press a button with their left or right hand up to 10 seconds before the subject became aware of having made that choice. “How can I call a will ‘mine’ if I don’t even know when it occurred and what it has decided to do?” asks study co-author John-Dylan Haynes, a professor at the Bernstein Center for Computational Neuroscience in Berlin.

But before we jump to the conclusion that when it comes to prayer — or anything else — our brains “make us do it,” many scientists say otherwise. Mario Beauregard, a Canadian researcher with a PhD in neuroscience and the co-author of The Spiritual Brain: A Neuroscientist’s Case for the Existence of the Soul, is at the head of the pack, arguing that humans “aren’t biological machines controlled by physical processes in the body.” Beauregard cites neurotheological studies on the impact of prayer to bolster his argument, along with the placebo effect, evidence of consciousness during cardiac arrest and various studies related to near-death experience. “Our beliefs alter our brain. The mind and consciousness affect us on an atomic and subatomic level,” he says.

While Persinger says his work is attacked by the religious right, Beauregard claims mainstream thinking is controlled by secular humanists. “It’s an ideological battle. Young scientists are afraid to come out in support of the new science because they are afraid for their jobs and losing grants.” Last February, he launched an online petition called the “Manifesto for a Post-Materialist Science” urging academics to put their non-materialist world views on record. So far, of the 61 academics who have signed, most hold professor emeritus positions and, according to Beauregard, have less at stake in the debate. “It will change in 20 or 30 years anyway. We are in the midst of a scientific revolution. There is no stopping it.”

There is no doubt that prayer has a powerfully positive effect on the brain. How it works remains a mystery; why it works, even more so. While the studies raise a broad range of philosophical issues, at the heart of the debate is the very nature of God. Newberg’s conclusion is cautious: “Maybe it’s not the brain that’s creating the spiritual experience, but it may be the way God interacts with us. There really is no way to tell from a brain scan what the reality of the prayer experience is.”

Rev. Trisha Elliott is a minister at City View United in Ottawa.

CANADIANS AT PRAYER: 4 SURPRISING FACTS

By Cory Ruf

A rosary clutched between clenched fists. A head bowed reverently in the direction of Mecca. The low moan of a centuries-old mantra sung to summon blessings from the gods. Prayer, in its many forms, is an ordinary sight in many Canadian homes and places of worship.

But despite its ubiquity, the extent to which prayer pervades Canadian life remains something of a mystery, even to academics studying the country’s religious landscape. According to Michael Wilkinson, director of the Religion in Canada Institute at Trinity Western University in Langley, B.C., there is a dearth of fine-grain empirical research on precisely how prayer is practised across the country. Public opinion polls only occasionally ask about spirituality, he says. And when they do, “none of the research is focused specifically on prayer. It’s always been, ‘Do you pray? Yes or no. If so, how often?’” Wilkinson laments. “The problem with that is we have no idea who is praying, where they pray or how they pray.”

The 2012 General Social Survey (GSS) offers some of the best and most recent data on prayer in Canada (though it, too, leaves many questions unanswered). Statistics Canada conducts the survey annually, each time polling more than 20,000 Canadians about their lifestyles and cultural attitudes. The focus of the survey changes regularly — volunteerism and family are examples of recurring themes — but questions about religion pop up in every cycle. Using results from the survey and a few other measures, one can paint, in broad strokes, a portrait of the state of prayer in Canada. Here are four findings:

1) Many of us pray. According to the 2012 GSS, nearly two-thirds of respondents reported praying, meditating or undertaking religious worship on their own in the previous year. More than half (55.8 percent) said they engaged in this kind of solitary spiritual reflection at least monthly, while 30.5 percent said they didn’t pray at all.

Canadians, however, are not as prayerful as their neighbours to the south. A 2013 study by the U.S.-based Pew Research Center suggests that 55 percent of Americans pray daily.

2) New Canadians pray more often than their Canadian-born counterparts. Around 40 percent of the GSS respondents who were born outside Canada said they pray, meditate or engage in individual religious worship daily. Among Canadian-born survey takers, that number was 29.4 percent.

Perhaps it shouldn’t come as a surprise that born-and-bred Canadians don’t pray as much as their immigrant counterparts. GSS data compiled by the Pew Research Center shows that, between 1998 and 2011, the proportion of foreign-born Canadians who attended religious services at least monthly remained roughly stable at 43 percent. During the same period, attendance rates among non-immigrants fell by more than a quarter, from 31 percent in 1998 to 22 percent in 2011.

3) Canada’s religious landscape is becoming more diverse. Immigration has affected nearly every aspect of Canadian society. Religion, and by extension, prayer, is no exception. In 1981, census data show, 88 percent of the Canadian population identified as either Catholic or Protestant. Only four percent reported belonging to other religions, including, for example, Hinduism, Islam, Sikhism and Buddhism, as well as strains of Orthodox Christianity. By 2011, according to the National Household Survey, the “other” category had swelled to represent 11 percent of Canada’s 33.5 million people. All of these traditions, needless to say, come with their own distinct beliefs and rituals.

4) Prayer (or something like it) is common among people with no ties to religion, including atheists. Around 17.5 percent of the respondents to the 2012 GSS reported having “no religion.” Among that block, 22.7 percent said they participate in solitary spiritual practice at least monthly. “I think there is a desire for what I call the ‘off-label benefits’ of religious community,” says United Church minister Rev. Gretta Vosper, a self-described atheist and author of Amen: What Prayer Can Mean in a World Beyond Belief. Citing the work of American neuroscience researchers Andrew Newberg and Mark Waldman, she notes that meditation and deep self-reflection evoke the same positive feelings — of compassion, calmness and focus — in the brains of non-believers as prayer does in people of faith. “The benefits are physiological, neurological, social and emotional — all of those things are part of what we’re doing [when we pray],” says Vosper, minister at Toronto’s West Hill United. “People who have no religious belief can experience those benefits as well.”

Cory Ruf is a journalist in Burlington, Ont.

THE MYSTICAL SIDE OF PRAYER

Science can examine your brain at prayer, but it can’t help you connect with God. That’s where an ancient tradition comes in.

By Bruce Sanguin

Entering seminary 36 years ago, I naively assumed that my education would go beyond merely learning about God. I expected help to know God. But the curriculum was aimed squarely at my mind: systematic theology, liturgy, Bible history and so on.

Courses on contemplative prayer were offered at the Roman Catholic colleges down the road. But few Protestants enrolled. That form of prayer, we worried, led to “quietism,” a withdrawal from engagement with the real world. We were more focused on knowing God through scripture and preaching — mostly about social justice. Over the years, however, I’ve found that folks in the United Church congregations I’ve served do want to learn how to pray and to know God.

Among liberal Protestants, there is general agreement that the lowest form of prayer is petitionary — asking God for stuff. Petitionary prayer raises questions that drive the rational mind batty. For one thing, does it have any meaning in a world informed by science to pretend that God is out there somewhere, like a satellite dish to whom we beam our prayers, hoping that they are received? Do we imagine that without our prayers, God doesn’t know our needs? Or that our prayers move God to act in a way that God wouldn’t otherwise? It doesn’t matter whether the prayer is for a new car, Aunt Sally’s healing or world peace. For the postmodernist churchgoer, this kind of prayer has a high cringe factor.

And yet, we shouldn’t be so quick to dismiss petitionary prayer. Prayer is all about transcending the rational mind. At best, it’s transrational or beyond rational in a way that transcends, but includes, reason. Prayer is about tapping into higher forms of mind such as intuition and, ultimately, into the divine mind.

I recently accompanied the love of my life through a surgery. The first few days of recovery were excruciating because the painkillers heightened her anxiety. In her desperation, she asked me to pray with her. I prayed unhesitatingly that Jesus be present and use me as a channel of healing. The room filled with an energy that I experienced as a sweet stillness. For the duration of her recovery, Jesus was a more effective painkiller than all the opiates on offer. Don’t ask me to explain it.

Jesus encouraged us to ask for what we need. The Lord’s Prayer itself is an extended petition — for daily bread, forgiveness, to be saved from temptation and delivered from evil. Jesus tells his disciples that just as any father wants to give his children good things, so we can ask God for whatever we want and expect to receive it. “Ask and it will be given to you; seek and you will find; knock and the door will be opened to you” (Matthew 7:7).

But if it’s your ego making the ask, don’t hold your breath. The trick seems to be submission to the divine will. “Seek ye first the Kingdom of God, and God’s righteousness, and all these things shall be added unto you” (Matthew 6:33). Before any petition is mentioned in the Lord’s Prayer, God is confirmed as actual (who art in heaven), hallowed and submitted to (thy will be done).

When this pattern of prayer is sincere, it’s safe to say that we’ve exited the realm of ego. Submission to the will of God establishes connection with the divine heart and mind. To use a metaphor from John’s Gospel, when the branch is connected to the Christ vine, we will bear fruit in the world, and God will give us “whatever we ask” (John 15:5-8). By feeling our connection to the ever-abiding Presence in prayer, our ask is coherent with what God wants to give.

Prayer, then, is a response to a pre-existing condition of being intimately entangled with the reality that religions call God. It is initiated by the soul’s love of the most true, the most beautiful and the most good. Prayer is the response of the soul to the Love that is God.

The working definition of prayer that I learned from the Roman Catholics in seminary was that of eighth-century theologian John of Damascene: “Prayer is the raising of one’s mind and heart to God.” But the great mystics of every religion have intuited that it’s not us but God who does the raising. We are raised to the mind and heart of God when we can silence our minds long enough to discover the ever-present One who desires to be united with us.

The Jesus lineage has generated many different forms of prayer throughout history — all focused on silencing the rational mind. The Jesus Prayer originated with the fourth-century desert fathers and mothers, who understood that silence requires more than finding a secluded cave in the desert. The real raucousness takes place between our ears.

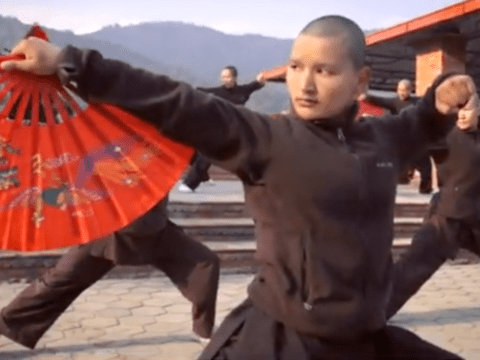

To quiet the mind, they recommend repeating the phrase, “Lord Jesus Christ, Son of God, have mercy on me,” with head bowed toward the heart. The Cloud of Unknowing, a 14th-century spiritual classic, is also focused on silencing thoughts through the use of a single word, like “love,” repeated over and over again. The intent is to offer oneself completely to God through love. “By love, God may be grasped and held. By thought, never.”

Centring prayer is another form of prayer popularized by Fr. Thomas Keating, who uses a sacred mantra, such as “God is love,” to quiet the mind. First, one sets the intention to consent to the presence of God; then, one introduces the sacred mantra. Whenever a thought or image arises, it is a signal to return to the mantra. With practice, one discovers times when neither thoughts nor the mantra is sounding. Here we simply rest in the presence of God, a deeply nourishing, fulfilling and joyful state.

On the other hand, 13th-century mystic Meister Eckhart is a bit grumpy, to say the least, about any techniques or paths to God. There is no path to God, because God is the path, he says. Those who seek God by way of a technique end up mastering the technique but missing God. What is required above all, according to Eckhart, is detachment. From what? “Start with yourself therefore and take leave of yourself. Truly, if you do not depart from yourself, then wherever you take refuge, you will find obstacle and unrest, wherever it may be.”

Realize, says Eckhart, that God is not a being, but the Ground of Being. Drop into the gift of the Ground of Being that is your most intimate self; relinquish all other notions of self as false constructions; and experience union with God. Otherwise, he exhorts, “stop flapping your gums about God.”

Like Eckhart, Jesuit priest Jean Pierre de Caussade, born in 1675, was suspicious of prayer techniques. His book, The Sacrament of the Present Moment, teaches that as we abandon our will to the divine, we discover that our very lives, in all their ordinary details and duties, are being lived by God.

As we mindfully attend to all that arises in the course of a day, our lives become sacraments. This orientation has the potential to make mystics of us all. When we assume that we are always and everywhere being lived by a divine heart and mind, we can surrender in humility to this grace and come to know God and God’s ways directly.

Rev. Bruce Sanguin is the author of five books, including If Darwin Prayed: Prayers for Evolutionary Mystics, winner of an IPPY gold medal. His teaching website, Home for Evolving Mystics, is www.brucesanguin.com.