In June 2015, Broadview’s predecessor publication, The United Church Observer, published an essay titled, “Do We Still Believe That Something Vital Is in the Making?” The occasion was the United Church’s 90th anniversary, and the writer was Phyllis Airhart, author of A Church with the Soul of a Nation: Making and Remaking the United Church of Canada (2014). Today, Airhart is professor emerita of the history of Christianity at Emmanuel College, University of Toronto. To mark the United Church’s centennial this month, she collaborated with Broadview to reformat and update her original piece. We begin with her provocative opening salvo.

You may unsubscribe from any of our newsletters at any time.

The United Church of Canada’s ‘death wish’

Does The United Church of Canada have a death wish? Has that question ever crossed your mind as you stewed over unflattering comments about one of its controversial positions? Is this a church that is willing and even wanting to die for its convictions?

If a reporter had put that question to some of the thousands leaving the Mutual Street Arena in Toronto on June 10, 1925, they might well have answered yes. Much of the publicity for the event had billed it as the birth of The United Church of Canada. The sermon they heard that day, however, was a sombre reminder that discipleship demands sacrifice and sometimes even death.

The elegant 37-page order of service gave few hints about the sermon. Scheduled after the formal declaration of church union, it was tersely listed as “Communion sermon (by Minister appointed).” As Methodist Rev. S.P. Rose from the Wesleyan Theological College in Montreal strode to the pulpit, the audience perhaps expected to hear him preach on the scripture passage read earlier, John 17, with Jesus’ prayer “that they all may be one” so often quoted by proponents of church union.

Instead, Rose read John 12:24-32, and delivered a sermon focused on one verse in particular: “except a kernel of wheat fall into the ground and die, it abideth alone; but if it die, it bringeth forth much fruit.” Challenging his listeners to embrace a willingness to die in order to “enter into a larger life,” Rose pressed the point that the grain of wheat that does not die will perish.

The dying wheat image must have been a poignant one for those who moments before had ceremonially relinquished their old institutional names and symbolically bequeathed a prized feature of each tradition to the United Church as an “inheritance.” The ritual captured the paradox that had brought them together: they intended to be a life-giving presence in communities across Canada in the future — and were willing to let their separate denominational identities die to make it happen.

The United Church’s founding vision

The United Church has never shied away from putting its identity on the line. When Methodists, Congregationalists, most Presbyterians and congregations already operating as union churches launched the denomination, the founders let go of some of their distinctiveness — their “peculiarities,” as they put it — to build a church united by what they held in common. They believed their venture would not only improve operational efficiency, but also create better persons, better communities and a better nation. That conviction provided a positive rationale for the difficult decisions that followed, such as closing or amalgamating congregations in some places to open new ones in others.

In a sense, the founders succeeded beyond their wildest dreams. The early 20th century was a time when most Canadians still assumed the mutually beneficial relationship among religion, politics and culture associated with “Christendom.” The United Church adapted to that ethos by presenting itself as well suited to meet the spiritual needs of the young nation. Its claim to be “made in Canada” gave it a boost in the early going.

More on Broadview:

-

United Church moderators reflect on the past, present and future

-

United Church unveils colourful photo reimagining ‘Last Supper’

Moving from ‘surviving’ to ‘amazing’

It’s easy to forget that the existence of the United Church, let alone its survival, was far from certain. Church union had been discussed in other countries but never attempted on such an ambitious scale. A dissenting group of Presbyterians bitterly contested the decision to unite and many voted to remain Presbyterian.

As the United Church’s 10th anniversary approached, one could almost hear the collective sigh of relief. Principal Edmund Oliver of St. Andrew’s College in Saskatoon placed “It has survived” at the top of his list of “Our Achievements” in a commemorative pamphlet. Despite economic depression and war, more achievements were to follow.

To co-ordinate activities across the nation and around the world, the new denomination set up a strong national structure with a burgeoning executive staff, centralized fundraising and fund allocation, and boards with specialized functions. Despite its claims to efficiency, this organizational culture drew criticism. The emphasis on preaching and faith formation that was paramount for congregations competed with the denomination’s regional and national priorities. Very Rev. Richard Roberts, moderator from 1934 to ’36, warned that a church organized like a department store “was under sentence of death.” He saw preoccupation with statistics as a worrisome sign, “as though it mattered very much how many of us there are, when the real matter is what kind of people we are.”

Roberts did not live to witness the postwar boom in membership, but it’s not hard to imagine him warning that bigger is not always better — even in department stores. By mid-century, the United Church had met and even exceeded growth expectations. “Amazing” is often used to describe this time of new church buildings, sanctuaries filled for Sunday worship and church schools bursting at the seams with children.

The church in a post-Christian Canada

By the end of the 1960s, the United Church’s “glory days” were already behind it. The vision of a Christian Canada that the founding generation took for granted was collapsing in the wake of a cultural revolution.

The United Church met the challenges ahead by daring to change policies and practices. For instance, in 1962 it took what was considered a shocking position on remarriage of divorced persons, acknowledging that divorce is sometimes a better choice than remaining unhappily married. And although Lydia Gruchy had been ordained in 1936, it was not until the 1960s that the church approved ordination for married women. The push for women’s equality was a precursor to other social justice initiatives related not only to sexual and gender diversity, but linguistic and racial inclusion as well.

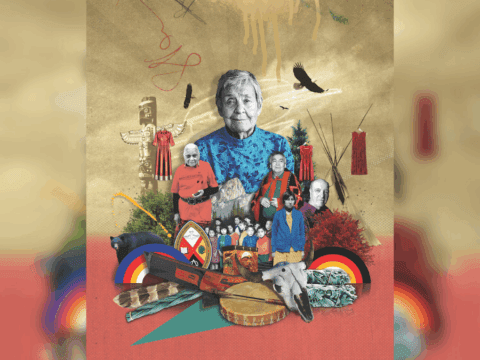

A 1966 report on world missions was also consequential in years to come. Its recommendation that the church “should recognize that God is creatively and redemptively at work in the religious life of all mankind” signalled openness to other faiths and to cultivating ecumenical and interfaith relationships. By inviting reflection on United Church missions, the report laid the groundwork for an apology in 1986 to Indigenous Peoples for having confused “Western ways and culture” with the Gospel. A second apology, in 1998, acknowledged the tragic consequences of the United Church-run residential schools.

Want to read more from Broadview? Consider subscribing to one of our newsletters.

Facing the challenges of the next century

The founding generation’s assumptions about the interplay of church and community are not so obvious now. Recent studies show that many Canadians approach religion as consumers with personal needs, rather than as both a religious and civic obligation. The benefits of organized religion are disputed, and some believe it causes more social problems than it solves.

Disaffiliation, decentralization and deconsolidation have tended to leave us to our own devices — literally in some cases — to make sense of the world. New technologies are changing what it means to belong to a community of any sort and complicating old questions about the purpose of the institutional church. Artificial intelligence will accelerate the already dramatic impact of digital technology, blurring boundaries and altering our sense of time and place. Old ways of operating no longer work as they did in the past — for banks, news media, political parties or retailers, let alone churches.

COVID-19 brought another disruption with pandemic health regulations that prohibited in-person gatherings. Meeting as the body of Christ at the same time and place was, for some, a habit that was lost without practice. Even after in—

person services resumed, many congregations continued to provide digital connections for remote participation.

If such trends proceed apace, gathering in a building for worship at the same hour could someday seem as quaint to future generations as the notion of “Christendom” now seems to us. On the other hand, faith organizations may have an opportunity to fulfil a longing for authentic community that is not satisfied by an iPhone or chat bot.

Predictions of extinction

The United Church — and Christianity in Canada, for that matter — has lost the reinforcement that a cozier relationship with the dominant culture once provided. The United Church is no longer the fresh new face on the religious scene that it presented to the world in 1925; instead, statistical analyses of the mainstream Protestant churches suggest more gloom ahead. With the loss of Christian memory, it is as easy not to be a Christian as it is to be one. The United Church has succeeded in drawing attention to social justice issues such as gender and sexual equality, racial justice and the climate crisis, but the denomination itself is widely perceived as failing. Churches have not escaped the general distrust of institutions; the revelation of sexual, physical and emotional abuses by some church leaders has added to it.

That said, the denomination has (so far, at least) defied statistical projections of its passing that have dogged it for decades — including one from its own consultants in the late 1960s that showed it would have no members in Toronto within 15 years.

The United Church’s ongoing transformation

“Making” the United Church in 1925 was possible because its founders refused to be tied to a fixed view of the church or the world. What I described in The Church with the Soul of a Nation as its “remaking” in the 1960s grew out of a similar conviction: that the church is not called to escape time and place, but to engage them more faithfully. The United Church that emerged after that tumultuous decade still resembled the church that had come into being in 1925. But it stepped toward the future with new models of worship and fellowship, a new creed, a new organizational design and a renewed emphasis on ministry in and to the world.

Will future historians see what is now happening in the United Church as another remaking? Or will its name disappear, perhaps to make way for something new? Recent changes suggest it is living through a time that could be as consequential as the 1920s or 1960s. The 2019 organizational restructure continues to evolve. The new strategic plan is reshaping its identity and guiding its programs. A new hymnbook will have an impact on worship. In its spiritual practices and governance, the church is drawing on traditional Indigenous ways. And the development of an autonomous Indigenous Church is ongoing.

Looking forward, with faith

I have a hunch that those who celebrated the inauguration of the United Church would be pleased that it is still willing to shoulder the risks of change. That is, after all, what Jesus’ followers have been doing for generations — not only the multitudes meeting in Toronto’s Mutual Street Arena in 1925, but the little group huddled together in Jerusalem in the even more distant past.

Are we not like those first followers of Jesus — uncertain, unsure who Jesus is, but occasionally finding the grace of our Lord’s presence amid ordinary living? Are we not like the thousands who left the Mutual Street Arena not knowing whether anything or everything was about to change?

What we do know is that the Christian faith assures us that God is with us, not only when we are most assuredly “amazing,” but even when we are not. We are called to witness to that presence: a God who can infuse new life even in something that carries the whiff of death and decay. As Christian philosopher G.K. Chesterton once reminded his readers, “Christianity has died many times and risen again; for it had a god who knew the way out of the grave.”

***

This article first appeared in Broadview’s June 2025 issue with the title “Birth, Glory Days and Beyond.”

Phyllis Airhart is professor emerita of the history of Christianity at Emmanuel College, University of Toronto.

Thanks for reading!

Did you know Broadview is the only media organization in Canada dedicated to covering progressive Christian news and views?

We are also a registered charity and rely on subscriptions and tax-deductible donations to keep our trustworthy, independent and award-winning journalism alive.

Please help us continue to share stories that open minds, inspire meaningful action and foster a world of compassion. Don’t wait. We can’t do it without you.

Here are some ways you can support us:

Thank you so very much for your generous support! Together, we can make a difference.

Jocelyn Bell, Editor/Publisher, CEO and Trisha Elliott, Executive Director