Fraser Presbytery is situated along British Columbia’s Fraser River valley. It spans from the bustling suburbs of Delta, White Rock and Surrey in the west, and beyond the cities of Abbotsford and Chilliwack in the east. The region has seen exponential growth in its population and economy over the past 25 years. But except for a new Taiwanese church, every one of the 25 congregations that make up Fraser Presbytery is shrinking.

It may be because the Presbytery also happens to be situated in Canada’s most secular province. Here, about 60 percent of people either claim no religious affiliation or don’t attend religious services, and even among the faithful, congregations compete for time and commitment with sports and leisure activities. Or it may be that many of the mostly Asian immigrants, who provide the bulk of the area’s population growth, are not Christian. Of those who are, only a few are attracted to the United Church.

You may unsubscribe from any of our newsletters at any time.

Though the challenges facing the congregations of Fraser Presbytery are pronounced, they are by no means unique — and the rest of Canada is not far behind. Nationally, people who have no religious affiliation or don’t attend worship rose to 44 percent from 31 in the last 20 years. The United Church has declared itself intercultural and encourages congregations to welcome people of all ethnicities. But beyond culturally separate ethnic ministries, many congregations are struggling with the concept. So United Churches seeking a sneak preview of their own congregational future should watch British Columbia. Those looking for possible answers to their own struggles should watch Fraser Presbytery.

About two years ago, the churches of Fraser Presbytery decided to take a hard and honest look at what secularization, a younger and more culturally diverse population and the aging of their “core constituency” might mean for the future of their congregations. A report by consultant Derek Evans, looking at strategic planning for future ministry, produced what church leaders now refer to as a “wake-up call” or “reality check.” A bucket of cold water in the face may be a better description.

Using population and demographic statistics plus the congregations’ own data, Evans outlined a 10-year pattern of decline (from 1995 to 2005) that showed drops of 23 percent in the number of financially supporting households, 24 percent in Sunday attendance (steeper than the 15 percent decrease in membership) and 51 percent in church school participation across the Presbytery.

“Nothing was really surprising,” says Rev. Joan McMurtry, minister at First United in White Rock, B.C., and current chair of Fraser Presbytery, “but it was hard to see it in graphs and pictures and stats what the trend would be if we did nothing different.” It was “in your face.”

A simple projection of trends 10 years into the future was frightening: 15 to 17 remaining congregations, 20 percent fewer financial supporters and church schools once again cut in half. But the news worsened. The consultant also reported that if nothing was done to alter the trends, the drop in numbers would more likely “reach a ‘tipping point’ at which the rate of decline becomes exponential.” So 10 years might be generous.

The consultant offered three options: “Do nothing” and wind up in 10 years with three or four healthy congregations among about a dozen survivors; “Circle the wagons” by offering program planning and financial resources, forming regional clusters of congregations, closing about a dozen congregations and saving a mix of small neighbourhood and medium-sized program congregations; or “Clear the decks” by closing most of the congregations and developing three to five regional churches with high-quality programs, staff, music, worship and small groups.

Evans also offered a new mission statement and several key directions that would move Presbytery away from congregational autonomy and volunteer management, and toward regional professional staffing and focused strategic planning.

The Presbytery, for its part, rejected the proposed mission statement and through a discussion process with consultant Chris Corrigan (Evans has moved from the area to work in Ottawa) developed its “Vision for Mission” document and to-do list.

Many of those who attended consultations following the report’s release supported Evans’s most radical proposals.

But the approach officially adopted late last year was a variation on the middle-ground “Circle the wagons” option, with Presbytery supporting training for intercultural and intergenerational ministries, forming six congregational clusters, and working toward hiring a dedicated Presbytery staff person and injecting significant financial resources (if money from property sales is made available).

Some tangible efforts are already under way. Over two days in early March, Fraser Presbytery met at Colebrook United, a pretty 1970s-era stone-and-wood church in a leafy middle-class neighbourhood in Surrey. The church’s bright, airy hall, like many renovations at churches in the area’s growing suburbs, was completed within the past decade.

The meeting itself is punctuated by good news. Work in clusters ranges from shared educational events in White Rock to a large youth group in the Abbotsford area to more serious talks of reorganization and work with a paid consultant in Langley and the surrounding area.

A new Taiwanese congregation, Amazing Grace United, was planted in Surrey seven years ago and has now taken over the former home of Oak Avenue United. Newcomers from Korea have begun attending Trinity Memorial United in Abbotsford, with the help of a pastor funded by a Korean overseas ministry. Most are mothers with children, whose husbands are still working in Korea.

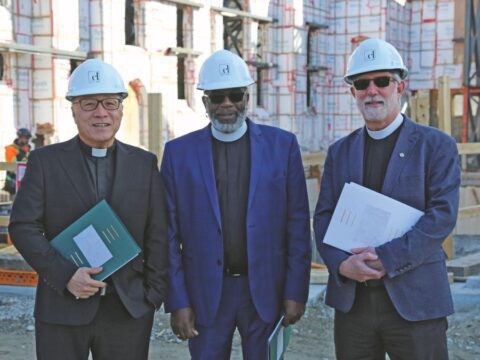

Reminders abound, however, that evolution requires constant learning and doing. Worship includes a story about building and unbuilding; there’s a presentation on how to present intergenerational ministry; Crossroads United, an amalgamation of two churches completed last year, announces it has chosen an architect for its renovation project; a volunteer team walks everyone through ways to work with demographic data purchased from Environics for every church in the Presbytery; and chairperson McMurtry ticks off a list of goals that are part of the Presbytery’s newly minted vision.

Fraser Presbytery’s deep pockets will certainly help ease the transformation. The Evans report showed property holdings worth about $65 million. Some has already been liquidated to finance the changes. About $2 million from the sale of Royal Heights United will fund the Crossroads renovation; Aldergrove United sold its building for $2.5 million earlier this year and meets in rented facilities; part of Bethany-Newton United’s property in Surrey was sold for $1.85 million to clear a mortgage; and in Maple Ridge, Whonnick United’s building will soon be on the market as it moves toward amalgamation.

Despite the changes that money helps to finance, undercurrents of exhaustion, anxiety, frustration and confusion persist. Some ministers have been noticeably absent from Presbytery during the past year. Four congregations have interim ministers, and four ministers are on disability leaves.

Northwood United in Surrey is Fraser Presbytery’s largest congregation, but its 400-seat sanctuary is usually about half full. The minister, Rev. Will Sparks, says people “understand that we have to do something different. But they’re having a hard time seeing other ways of doing church.”

In Abbotsford, Rev. Dorothy Jeffery of Gladwin Heights United says the church “might be measuring the wrong thing” and should look at community impact instead of participation. “I’m concerned about the anxiety I always feel that we’re failing or going down the tubes,” she says.

The need for more youth work, cited in the Evans report, has long been recognized. But an existing Presbytery-wide initiative, complete with a full-time worker, fell apart last year partly because too little time and resources were spread over too wide an area. Two congregations are now hiring their own youth ministers, but time has been lost.

Regarding amalgamations, some congregations that look like ideal candidates are not seriously considering it. In White Rock, with three United Churches within a 10-minute drive, Sunnyside United voted against amalgamation talks last year. The other two have it on the back burner.

As visiting B.C. Conference personnel minister Treena Duncan reminded Presbyters at their March meeting, they are not alone on the road to change. “It seems like a long time that we’ve been in transition and we need a break, but we’re not going to get it.”

Perhaps inevitably, given the way the United Church works, any changes that do take place in Fraser Presbytery will come from congregations. Presbyteries can talk about strategic planning, then support and encourage change, but they can’t carry it out.

“Our governance makes it really difficult to close congregations, if that’s what you want to do,” says B.C. Conference executive secretary Rev. Doug Goodwin. “We just don’t have the experience with this kind of strategic planning . . . and don’t have the structure to be a diminishing church. We don’t have the freedom, the flexibility, the power.”

For now, the congregational cluster in Langley is the only one moving toward a new form of ministry. The four congregations involved — Jubilee, St. Andrew’s, Langley and Sharon United — are financially stable but all have accepted that community growth does not necessarily mean church growth.

Jubilee is in a kind of limbo after cancelling plans to build near the new Walnut Grove neighbourhood. After 10 years in an all-new community of 23,295, the congregation has only a small corps of faithful worshippers.

As part of Fort Langley’s historic neighbourhood and the oldest continuously used church building in the province, St. Andrew’s United is sure to survive as a physical structure. Its congregation is less certain of the future, though, and willing to consider new approaches. Langley United recently wrestled a $50,000 deficit to the mat but is also struggling with its identity as a family church in a busy downtown area.

Sharon United, in the upscale Murrayville community, built a $2-million addition five years ago to accommodate new worshippers, after years of two Sunday worship services. Faithful members have the mortgage paid down to about $700,000, but anticipated growth has not materialized. “People are realizing we have to do something,” says Sylvia Mountain, an active Sharon United layperson. “In a few years, we will be in big trouble.”

The Langley cluster churches have worked with consultant Chris Corrigan and assembled a leadership “dream team” to flesh out the form of their ministry together. They have got as far as talking finance and personnel and hope to unveil their plan for their congregations this month.

McMurtry calls it a “pilot project” for the Presbytery, and it may be a parish-style structure with one congregation and multiple locations. Or it could be closer to the regional church envisioned by Derek Evans. Whatever emerges from all of the discussions, consultations and brainstorming, says Jubilee United’s minister Rev. Louise Cummings, “it won’t be traditional church.”

As far as Doug Goodwin is concerned, that kind of congregationally rooted change may be the church’s only hope for the future. The administrative courts of the church “need to be really flexible, to allow mistakes, allow experimentation and then just let congregations go nuts. Whatever form those congregations come up with should be fine,” he says. “I just don’t think we know what the church will look like in 30 years.”

***

This story first appeared in The United Church Observer’s June 2010 issue with the title “A wake-up call.”