It’s a fractured nursery rhyme played out across the United Church. “Here is the church. Here is the steeple. Open the doors. There aren’t enough people.”

Wait — don’t stop reading! This isn’t another sad tale of declining attendance. It’s the story of congregations who took ownership, forged new relationships and moved forward.

You may unsubscribe from any of our newsletters at any time.

In the last five years, almost 200 United churches have been involved in amalgamations. Some of those mergers were simply survival tactics. But that’s not the case in the stories that follow.

Let’s start with the five-year-old Kitchissippi United in Ottawa. The name is Algonquin, meaning “a mighty river”; the image of three small streams flowing together is one that the new congregation embraces.

Indeed, the three founding “streams” had each, at one time, been strong: Westboro United, in those heady post-war years, had known Sunday schools of 800 kids; Northwestern United had thrived as a smaller congregation intensely committed to social justice; and Kingsway United had been a warm community church with a wide range of programs.

But that was then.

While all of the churches were still viable (to varying degrees) before coming together, they saw the writing on the wall: smaller congregations, aging buildings, disproportionate energy spent just keeping the lights on.

The merger started with informal conversations among three active lay leaders; others quickly joined and the process went smoothly.

Rev. David Sherwin, one of Kitchissippi’s transitional ministers, says, “A key factor was that there were three congregations, not two. So the conversation never devolved into us-them.” In 2008, the three churches closed, and a new one, Kitchissippi, was born.

These days, according to current minister Rev. Jenni Leslie, “the vision is still unfolding” in a context that is “very hopeful and full of energy” with “lots of volunteers and no acrimony.” Community outreach ministries are developing; Godly Play serves a growing group of kids; a Right Relations Circle nurtures understanding with First Nations people, and “we’ve learned how to listen, and speak the truth.”

Now to Scarborough, Ont. Until recently, Wanstead United was a tiny, aging congregation. They loved their minister, a retired part-time layperson named Paul Neary; they wanted to stay together and continue to serve their community. But the neighbourhood was changing, the growth potential limited, and keeping the doors open was becoming a burden.

Nearby was St. Paul’s United. The Wanstead folk knew the people at St. Paul’s through shared activities, and they liked the minister, Rev. Leslee Alfano, who, as supervising pastor, had treated them with respect. They decided they would like to move, as a group, to St. Paul’s. But would St. Paul’s have them?

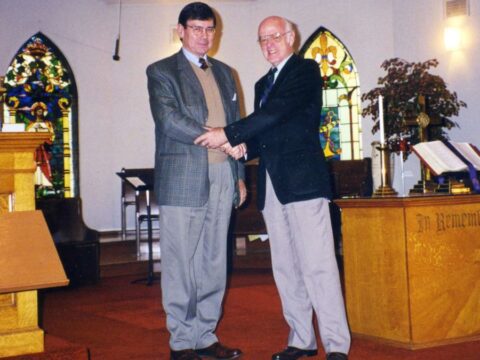

The approach was made in May 2012. Five months later, the marriage was consecrated. Last January, the Wanstead building closed and Alfano and Neary began a shared ministry at St. Paul’s.

The congregation is “growing like crazy,” says Alfano, with Sunday attendance averaging 125 people. Young families have joined, the choir loft is full, the leaky basement is fixed and new outreach projects have started.

“Wow, who knew?” exclaims Alfano. “It was Wanstead’s willingness to let go of their building, and their valiant effort to be faithful, that made it work.”

The good news is not confined to urban centres. In Quebec’s Gatineau region, the five congregations of Gatineau, Chelsea, Wakefield, Rupert and Cantley were averaging 65 to 80 worshippers — collectively. Something had to change, so a group of 18 people started to talk.

“I have never seen a group work so well together,” says Larry Seguin, one of its co-ordinators. “The conversations were spiritually based; everyone agreed we had to leave our baggage at the door and start a new thing.”

They began by looking at conventional United Church models, including a joint pastoral charge, but ultimately settled on the “community co-operative,” an experimental model that is already enjoying success in Ontario’s Seaway Valley Presbytery.

This past June, the congregations launched the West Quebec Co-operative. The five church buildings will remain for now, but there will be one budget, one constitution, one Board, one set of committees and one ministry.

The co-operative will make all decisions about each of the five churches, including whether to sell individual buildings. With less energy spent on survival, more energy is available for mission. According to Seguin, fatigue has been replaced by vigour, worry by anticipation, and despair by excitement.

So what’s the secret? What makes these amalgamations work, when others sometimes founder? Here are seven factors that made these amalgamations successful:

The heritage of the founding congregations is honoured.

At St. Paul’s, artifacts and activities from Wanstead have found a new home, and the congregation has committed to donating $96,000 to the Mission and Service Fund in honour of Wanstead’s 96th anniversary.

In West Quebec, all five buildings are being kept for now because, according to Seguin, everyone’s biggest worry was “Are we going to lose our building?” And Doug Patriquin, chair of the Board at Kitchissippi, emphasizes, “We were very, very careful about balancing and honouring the contributions of each congregation.”

The amalgamated congregation is committed to outreach.

In West Quebec, the desire to free up time, money and energy was driven by a dual focus: outreach to youth and ministry with the French community. Kitchissippi is investing a great deal of money and thought into community programming in the Carlington area, where the former Westboro United congregation was located. St. Paul’s is deeply committed to a community development program for children in Africa, while hosting countless local groups in their busy building.

The amalgamated congregation is adequately funded.

Many United Church folk will remember the 1970s and ’80s, when new congregations were so burdened with debt they didn’t have enough money to operate, never mind grow. Happily, in these recent amalgamations, Presbyteries allowed the congregations to use funds from the sale of their now-redundant buildings for viable ministries in their areas. They are starting with what Barb Wilkes of St. Paul’s describes as a “dowry” — right from the start, they can explore new possibilities.

Local lay people drive the amalgamation.

The United Church has a history of often-unhappy mergers driven by “outsiders” — Presbyteries, Conferences or even clergy. In each of these recent cases, however, lay members of the participating churches took the initiative and worked out the shape of the emerging congregation. As Wilkes says, “It’s working because we all want it to work.”

Clergy support the amalgamation.

Patriquin of Kitchissippi says, “Angela Bailey, our minister at the time, encouraged us to get started, then offered to leave so she wouldn’t force us to choose [between incumbent ministers]. The enthusiasm of Jenni Leslie, our current minister, is extremely important.” Wilkes of St. Paul’s says, “Without proper leadership, this wouldn’t have happened. Leslee [Alfano] is a great communicator.” Seguin of West Quebec says, “Garth Mundle [brought in to facilitate the discussion] was terrifically skilled.”

Presbytery supports the amalgamation.

Almost everyone contacted for this story said a version of this statement: “I’ve never been a big fan of Presbytery, but I can’t believe how much they’ve helped us work this through.” The key word, for everyone, was “helped”; Presbyteries actively supported, but did not control, the process.

Everyone listens. And listens. And listens some more.

One thing upon which all amalgamation veterans seem to agree is this: listening to each other is critical.

These merged congregations may be doing church in new and interesting ways. But bold vision, forward-thinking lay leadership, supportive clergy and church courts, a solid funding base and a commitment to outreach can revitalize any congregation, whether it’s amalgamating or not. As the folks in West Quebec say, “Plus ça change, plus c’est la même chose.”

***

This story first appeared in The United Church Observer’s October 2013 issue with the title “The secrets of a successful merger.”