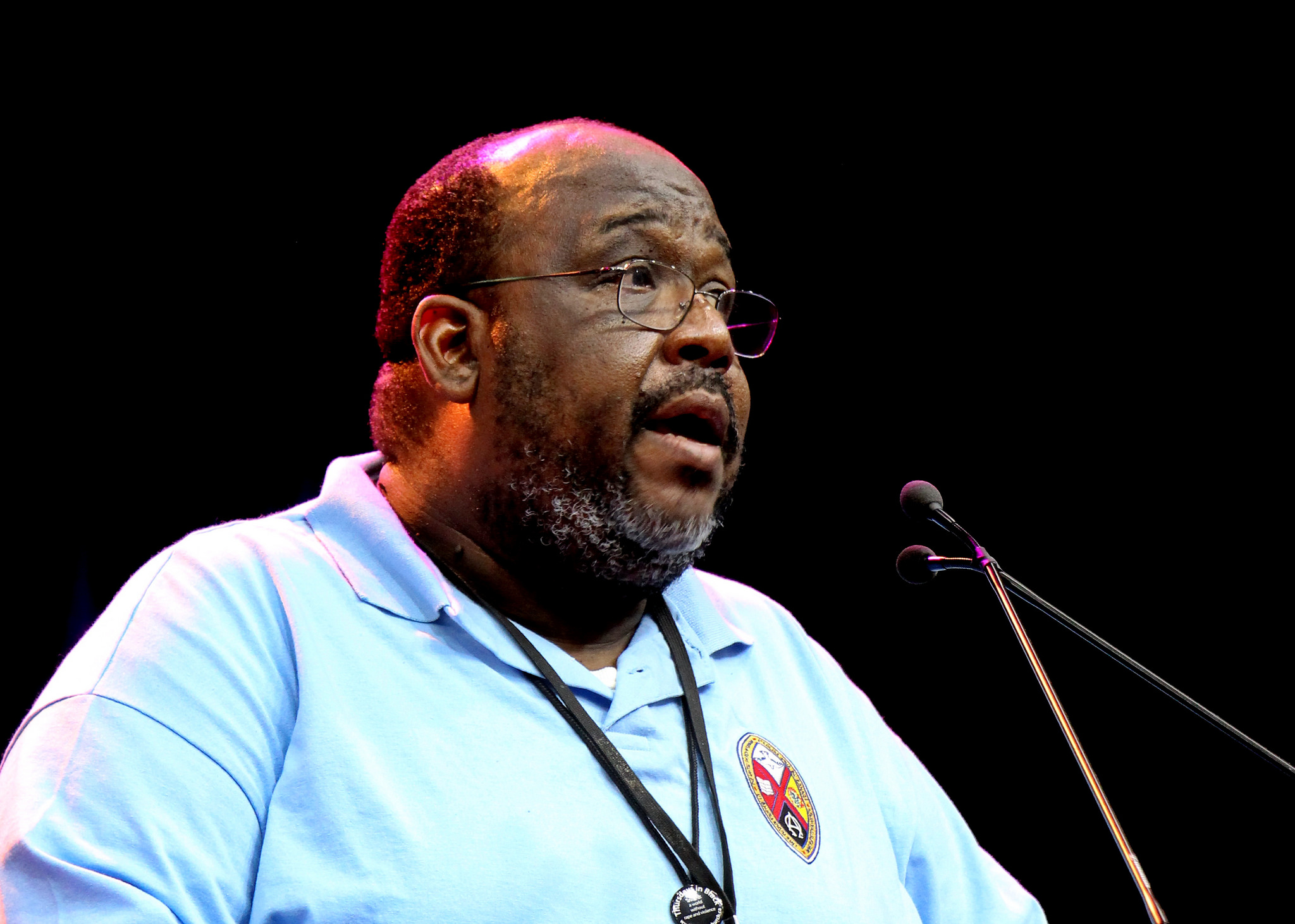

This message was delivered at General Council on July 27, 2018 in Oshawa, Ont.

First, let me say thank you for the opportunity given to me to serve in this capacity of intercultural observer at this General Council. I have been deeply moved by the privilege that has been afforded me and it is my hope that I have in some way, even a small way, done justice to the post.

You may unsubscribe from any of our newsletters at any time.

For my reflection, I want to share with you three stories from my experiences in the United Church of Canada. These stories have, in many ways, shaped and challenged my outlook in the church and my experiences this past week.

The first occurred a few years ago at a seminar on pastoral relations in Alberta. We were in small groups looking at a case study and the issue of race was involved. One of my white colleagues said to me, “you know when I see you, Paul, I do not see the colour of your skin, I just see a person.” To be clear, my colleague honestly thought he was paying me a compliment. However, in my response I had to say to him, “if what you say is true, then you have rendered me invisible. Invisible because you are not seeing who I am.”

I must confess that for the most part of the past week at General Council, I struggled with the feeling of being invisible. Invisible because in so many ways, I did not see myself, the experiences or cultures of those who like myself live in black or brown skins reflected in the corporate things we did in Council. It was almost as though we do not exist.

You can watch Walfall’s message in the video below.

Worship was good, and yet I was not seeing myself reflected in the worship. I long to hear the songs from the Caribbean or African or African American [communities].

I also felt invisible because, to date, I have yet to hear in the Council an acknowledgment that racism exists in our church and that the experiences of racism felt by every black person within the United Church of Canada are real.

Of the many proposals that have come before this 43rd General Council, I noted that there were only two that addressed issue of racism directly. Possibly we need to continue to attend to the issue of racism in our discussions.

Let us not forget that the ill we are seeking to confront is not only outside of the church, it is also inside the church. There has been no call to the church to acknowledge the reality of racism within it. There has been no challenge to church to confront the racism within it. There has been no urging of the church to transform or change from actions or attitudes which display white privilege, white entitlement and racism — transformation to become what the late Rev. Dr. Martin Luther King Jr. described as a beloved community. Acknowledge, confront and transform; A-C-T. We must act to end racism!

I have yet to hear in the Council an acknowledgment that racism exists in our church and that the experiences of racism felt by every black person within the United Church of Canada are real.

Part of the problem may well be that you have not stopped to listen to our story. Had you dialogued with us about our experiences and taken us seriously when we speak of the pain we have experienced simply because we inhabit black or brown skins.

If you had listened, then you would have heard the experience of the black minister who was told by his M&P (Ministry and Personnel) committee that he speak up and take whatever the church gives because it was out of pity that they took him from his poor country to be with them in Canada.

You would have heard the story of the female minister who had the experience of members not shaking her hand at the end of the service because they did not want a black minister in the first place.

You would have heard the story of the black female minister told by a search committee that they did not hire her because the congregation was not ready for a female minister, but in less than a month afterwards had recommended a white female minister to the congregation.

You would have heard the story of the black male minister who was called a “black boy who needs to be put in his place” by a member of a congregation. And there are many more stories I could add.

The reality is that my ancestors were taken from Africa and enslaved in the Caribbean, in North and South America. Their culture was ripped from them, they were dehumanized and made to feel that everything that was theirs was wrong. Slavery existed in Canada for almost 200 years and finally and completely came to an end on Aug. 1, 1838. While Canada hails itself to be the last stop in the underground railway for the enslaved fleeing from the USA, the reality of prejudice and systemic racism continues to be a feature of Canadian society. Next Wednesday, it will be the 180th anniversary of the complete ending of slavery in the former British empire. Let us not forget this anniversary.

So, I continue to struggle with this feeling of invisibility even while I continue to serve in the church.

The second story occurred in May 2015. At that time, I stood before the Alberta and Northwest Conference as a candidate for the post of conference president and the first thing I said in my speech to the conference was that “I am a black man.” The conference erupted with laughter and yet I do not think that to this day they understood what I was saying.

In many ways, I am a member of a minority, within a minority, within a minority. I am a black man, from the Caribbean and who is a recent immigrant to this country. Someone said to me that I may well be saying that I am microscopic. Possibly I am. But what I do know is that the view from where I am is different because my experiences are shaped differently. I look upon the church and honestly, I do not see what you have been, because I was not there for the past experiences. Instead, I see a church now and see what it can be. I see the things that are done which suggest time wasting and I also see the things which could be done differently. I see possibility and honestly, I see hope. Yet all that I, and those who are like me, are seeking to do is to offer this gift, of looking through a different lens, to the church.

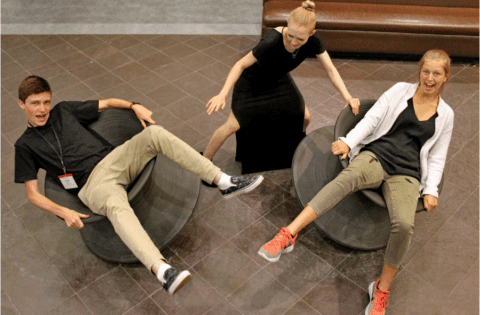

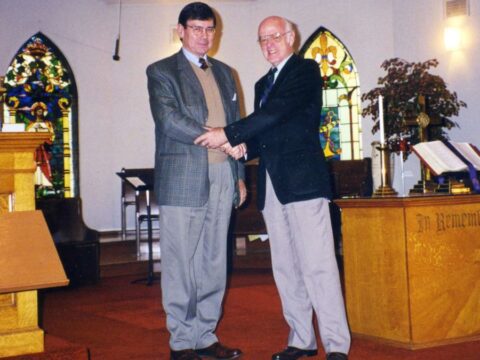

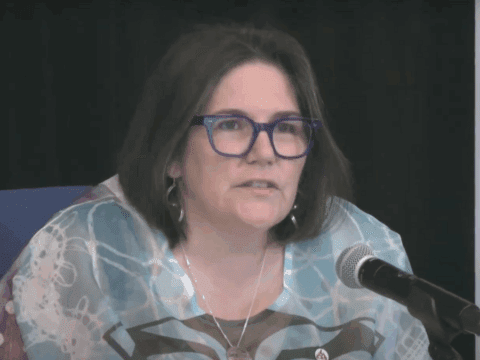

General Council 2018

Check out some of the best shots from the July 21–27 meeting in Oshawa, Ont. All photos courtesy the United Church of Canada/Flickr.

The third experience occurred in our conference executive meeting last October and our conference president, Dr. Kathy Yamashita, a woman of Japanese descent, reminded us that we should take note of who is missing from the table. Someone then reminded us that we are an intercultural church and therefore that may not be as pressing now as it once was.

But you know, I have been reflecting on the question, “who is missing from the table?” For in many ways, I now wonder if that is the real question to be asking. I am now very conscious that simply being at the table may be good, but it is not all that we may want to crank it up to be. The real issue seems to be “who are you at the table?” If I am at the table as your guest, then I am there to take whatever you put before me. I would hope that you will consider my needs but really you do not have to. I am at this table simply as a guest. If I am at the table because you are taking pity on me. Then even more so I take whatever I get.

But if you put me at the children’s table then while I am a member of the family, you would have taken away from me any right to speak about what I need. I have no way of influencing the menu.

But if you have me there as an adult and responsible member of the family, then I have a right to participate not only in the eating of the meal, I would then have the right to participate in the creation of the menu and in the preparation of the meal itself.

The issue for me is no longer only about who is missing from the table, but it is also about what is my place at the table. If you have accepted me there simply to tell me that I must accept what I get, then simply being at the table is not all that we have made it out to be. So, what am I doing at this table?

The answer to that question comes out when there is dialogue. When we take seriously each person’s experience and treat each person with dignity, respect and love. The answer comes when we do not make others invisible. It comes when each person’s unique perspective is valued. It is then that we will be an intercultural community. It is then that we will be the church that God wants us to be.

How do you cook chicken, my friends? I asked this question to a study group at St. Paul’s United Church in Edmonton. When I cook chicken — and I am no great chef — the first thing is that the chicken is seasoned. I would add the garlic, thyme, onions, green onion, pimento, paprika, black pepper and some soy sauce. If I was going to jerk the chicken, the mandatory jerk seasoning is added. All this is done from the night before I cook it and the chicken is left to marinate in the refrigerator.

When I cook, it will taste different to the chicken you cook. But you see, I offer this cooked chicken to you not because I believe that mine is superior to yours and neither do I believe it is inferior to the chicken you cook. All I know is it is different and I offer it simply asking that the different way I have done it be accepted and respected. All I ask is that you take my chicken and your chicken, and the chicken cooked by the indigenous, by the Korean and the Chinese and the many other cultures of people and let us share and delight in the differences and declare that is all good.

Let us take all the chicken we will cook and let us sit at the table of the church together. Let us ensure that the people who sit at the table are there not as guests but as valued members of the family. It is then that we will be able to look through the intercultural lens and have clear vision because we would have: Questioned our biases, challenged our assumptions, noticed who is missing, valued all voices, aimed for equity, and with a deep breath we would have lived out our commitments. Thank you.