Hunched over a stove in a log cabin on the northeastern edge of Lake Winnipeg in late 1840, James Evans, a balding 39-year-old missionary, toils away at a project that will make history. Having scraped the lead seals from tins of tea transported along rivers from Hudson Bay, he’s melting them. Then he pours the molten lead into clay moulds he has fashioned himself. When they’re cool, he grinds them smooth and, using a mix of sturgeon oil and chimney soot for ink, he creates his own printing press out of a Hudson’s Bay Company fur baler.

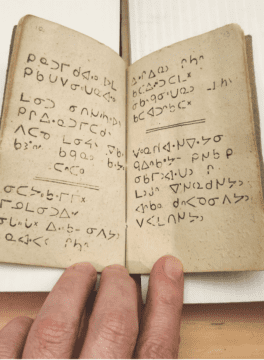

The goal of his labour: a new hymnbook for his congregation of Mushkego Cree. But this is not just any hymnbook. Released in 1841, this is the first book ever printed in what is now the province of Manitoba and the first ever printed using what in English are called Cree syllabics.

You may unsubscribe from any of our newsletters at any time.

In fact, the hymnbook is the oldest known example of that writing system, called ᒐᐦᑲᓯᓇᐦᐃᑲᐣ (cahkasinahikan or spirit markers) by those who use the language. The system is based on shapes that represent sounds, each a complete syllable rolling a vowel and a consonant into one. Thought to be the first and only phonetic writing system developed in what is now Canada, it is still in use and has spread among Indigenous and non-Indigenous communities around the world.

Significant as this moment is to the history of Canada, it has also become a bone of contention. No one disputes that Evans printed the first books in Cree syllabics, but did he develop the writing system himself?

Church history says yes. In almost every generation since that first hymnary was published, someone has written a book exalting Evans’s accomplishments as a Methodist missionary in Upper Canada and Rupert’s Land. That included inventing the syllabics. Articles, too, abound, hailing him as the genius linguistic pioneer. In fact, promoters of Christianity have used the tale for generations to highlight church work, publishing it in pamphlets distributed far and wide.

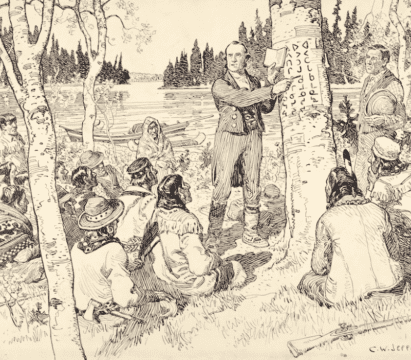

Drawings of the bright, energetic and distinctly non–Indigenous Evans teaching the new syllabary to amazed Cree have shaped the Christian imagination in Canada and abroad. “The Birch Bark talks!” the Indigenous crowd seems to exclaim in gratitude as a magnanimous Evans sketches the new characters on a birch tree or on a sheet of bark, according to a headline that accompanies one version of the tale.

This story is deeply offensive to Indigenous communities. It implies that settlers educated uneducated Indigenous Peoples and introduced them to birch bark as a form of communication. In fact, modern scholarship makes it clear that Indigenous Peoples had been using birch bark and had other written forms of communication long before settlers showed up. The church’s tale is the ultimate colonial self-congratulation.

Nevertheless, this is the story I took with me in 2016 when I attended my first classes in the Cree language at the University of Saskatchewan taught by Belinda Daniels, an award-winning teacher and speaker of ᓀᐦᐃᔭᐁᐧᐃᐧᐣ (nêhiyawêwin or Cree) from Sturgeon Lake First Nation. Daniels, who did her PhD dissertation on Cree language reclamation and is now professor of Indigenous education at the University of Victoria, told us a completely different story about how the syllabary came to be.

I recently called her to ask her to tell it to me again. “There is this man called ᒥᐢᑕᓈᑰᐁᐧᐤ (Mistanâkôwêw or Calling Badger) who died and came back alive again,” she told me, describing the man from the Great Plains Cree Nation in northern Saskatchewan. “While he was thought to have been dead, he was given the characters of the syllabic system, and he was taught how to write with the symbols.”

According to the oral traditions from which Daniels draws the story, when Calling Badger awoke from his trance, he wrote the symbols down on birch bark to show them to the people. Oral histories are passed down in many cultures in a deliberate and sophisticated way to preserve important information over generations. Western academics once dismissed these histories. Today, some Indigenous oral histories have been accepted in Canadian courts as reliable evidence.

More on Broadview:

-

Residential school survivor candidly reflects on experience in re-released book

- Truth before reconciliation

The syllabics, according to the oral accounts, were a gift from the spirit world for the benefit of the ᓀᐦᐃᔭᐊᐧᐠ (Nêhiya-wak or those who speak the Cree language). They came into being through a ᓀᐦᐃᔭᐤ (Nêhiyaw or Cree person), not a ᐊᔭᒥᐦᐁᐃᐧᔨᓂᐤ (ayamihêwiyiniw or missionary).

Indigenous Peoples across the Prairies and into the Anishinaabe territory in the east tell a similar story, although the name of the person and exact circumstances differ depending on where the story is told. The consistent theme is that the symbols came in a vision to an Indigenous person.

Two American anthropologists recorded Indigenous narrators telling the story in the mid-1900s. David Mandelbaum heard the story of Calling Badger from Chief Fine Day of the Sweetgrass First Nation in Saskatchewan in the 1930s. Verne Dusenberry received his version in an interview with Raining Bird of the Montana Cree in 1959. Mandelbaum was not inclined to believe the story. Dusenberry was, because the writing system was so different from Roman characters, and because he knew that the Cherokee had also developed their own form of writing.

So which story is true? First, there is the evidence from Evans’s own writings, meagre as it is. Rev. Geoffrey Wilfong-Pritchard, a United Church minister and teacher at St. Stephen’s College in Edmonton, has assembled these threads of information, including documents uncovered by his friend, the late Rev. Gerald Hutchinson. Hutchinson was a United Church minister who served Thorsby pastoral charge near Pigeon Lake, Alta., the site of a Methodist mission founded a few years after Evans printed the Cree hymnbook.

Wilfong-Pritchard concludes that the church’s version of the Evans story is a myth. “The people who are writing the biographies of James Evans were creating this whole world of a man who, you know, was very much cast in the Jesus mould and wanted to do nothing but good for humankind,” he says. However, “none of this is true.” Evans never claimed to have invented the writing system, Wilfong-Pritchard says. It is possible Evans learned the syllabics from the Anishinaabe while translating texts into Anishinaabemowin in Upper Canada, present-day Ontario. That was years before Evans worked with the Cree. One theory is that the Cree already knew spirit markers and had taught them to the Anishinaabe.

No overt written evidence or oral history exists that I am aware of to support that theory. Evans left no writing to say that he learned the symbols from others. But a missionary report written a decade after his death states he got the idea for the syllabics “from an Indian Chief.”

Evans certainly spent time with the Anishinaabe. He taught at mission schools with a bilingual English-Anishinaabemowin curriculum beginning in 1828. He was eager to develop a consistent system of spelling to help his students read and write in Ojibwe. In a letter to a Christian brother in 1841, he says that he had “prepared” an early version of the syllabics by 1836 and that they could be easily adapted to other Indigenous languages across the continent.

This suggests Evans had a working system of writing ready for use before he was sent out to work among the Cree. But he didn’t say he had invented them, exactly. Evans was evidently a gifted linguist who might have been capable of developing a new writing system. He wrote a book to teach Anishinaabemowin to non-native speakers. But he also collaborated closely with Indigenous colleagues in all his translation work.

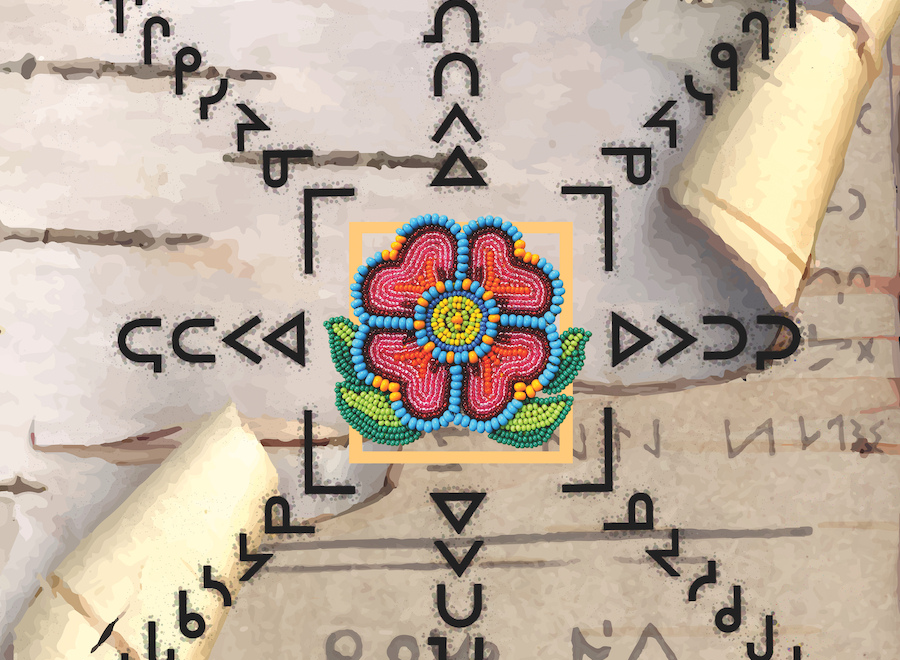

Then there’s the internal evidence within the writing system itself that speaks to its Indigenous origins. The shapes that make up the syllabics rotate in such a way that they point to the four cardinal and four intercardinal directions of the medicine wheel. “Each direction is associated with important teachings,” Daniels says. “Elders have taught me that each symbol represents a powerful spirit and a relationship.”

What has held some settlers back from believing Indigenous versions of the creation of spirit markers? Wilfong-Pritchard says the biographers of Evans drew on sources that were infused with the bias of settlers, part of a colonial mindset that justified taking Indigenous lands and establishing residential schools.

Conflict between denominations also shaped those sources. Methodists became jealous when an Anglican missionary took credit for the syllabics. So, Wilfong-Pritchard explains, they played up the role of Evans, the Methodist missionary.

Whatever their origin, the spirit markers have been widely and continually used ever since. The system spread quickly throughout the Cree nation. “The Cree, ᓀᐦᐃᔭᐊᐧᐠ (Nêhiya-wak), had one of the highest literacy rates in the world,” says Daniels. “At the time of treaty signing, they knew how to write their name; they signed their name in syllabics.” The system was reputed to be so easy to learn that it could be mastered in a day.

And Evans’s printed hymnbook may have played a more modest role in the spread of syllabics among Indigenous people than church history would suggest. Missionaries reported that the writing system was already in use when they first arrived in Indigenous communities. They assumed people had learned it from the hymnary, but that was not necessarily the case.

Even the Dene, a people who inhabit northern regions of North America and have a language much different from the Cree, learned the spirit markers. Missionaries on the shores of James Bay helped adapt syllabics to the Inuktitut language. Today, the Inuktitut-speaking Inuit of Canada have adopted it along with Roman letters as one of their two official scripts.

Missionaries to China also adapted a version of the syllabics, using East Asian ideograms, for people who could not read or write in their language of A-Hmao. Research by Hutchinson and Wilfong-Pritchard shows that these same Cree syllabics were likely the basis for Moon type, a parallel and contemporary system to braille that has been used to print reading material for the sight-impaired in more than 400 languages.

Spirit markers continue to enrich the lives of people everywhere, including the Cree, who are using them now to help restore their language. Daniels regards the markers as both sacred and a useful support in daily life: “They are a gift.”

But to whom do they truly belong? The missionaries or the Cree? After much of my own research and reflection, I think that’s the wrong question. Instead, I wonder what the two accounts of their beginnings have in common.

The two origin stories of syllabics seem to paint contradictory pictures of the past. Yet both versions agree on two important points. First, both say that Cree syllabics came into the world through a spiritual channel and for a spiritual cause. In other words, syllabics were meant to help connect people to the spirit world and to better their lives. Second, they agree that the medium for first communicating spirit markers was the bark of a birch tree. It’s clear that the land itself was intimately involved in the production and propagation of this system, a land that settler and Indigenous alike will continue to share for generations to come.

One way to tell the story is simply that the ᒐᐦᑲᓯᓇᐦᐃᑲᐣ or spirit markers arrived on this land as a gift to all, and that they are something we can celebrate, together, in the spirit of the generosity with which they were first offered.

***

Rev. David Kim-Cragg is a historian, author and minister at St. Matthew’s United in Richmond Hill, Ont.

Vanessa Kennedy, who served as a sensitivity reader for this article, is an Indigenous consultant in Hillsdale, Ont.

As a Cree person myself, I believe the syllabary was co-created. I believe James Evans did invent part of the syllabary, as he had 3 different versions of the syllabary. The initial syllabary was officially released in 1840, this first version had notches on the symbols to indicate “long vowels”. Version 2, he found that the symbols with notches in them did not have a consistent outcome regardless of the writing materials. So, he updated this syllabary by making the symbols that represent “Long Vowels” to be thicker. Version 3, he found that this also did not work as any writing material (Stamp, quill, or type writer) did not make consistent thicker or thinner symbols. Evans tried to make stamps to print the syllabary, but he had to make them himself as he did not get permission from official printing places. So in Version 3, it was a D. Ellis who introduced him to the use of dots over the symbols that represent “long vowels”. This final version is the version that is being used and taught presently.

Also, I do not doubt the Calling Badger story, but it is evident that James Evans might have gained the creation of the symbols from Pittman-Taylor Shorthand writing. There is also similar syllabaries used for different languages that seem to have similar symbols that is used in the Cree Syllabary. These other symbols from other languages would have existed before 1820, and Evans may have known about these other syllabaries from other languages and he took what would have best represented the sounds in Cree. Also, there are symbols in the Cree Syllabary that do not exist in any other language syllabary.

So, as much as I want to agree with this article. It is my opinion that the Cree Syllabary was co-created, parts of it could have come from the Calling Badger story, and also co-created by James Evans.