Murdo McDougall has a disease that didn’t exist for his people when he was born 78 years ago. Now diabetes affects one in seven, or nearly 500 people (including youth and children), in his community of Garden Hill, an Oji-Cree First Nation on Island Lake in a remote corner of northeastern Manitoba. Some, like McDougall, manage to live with it successfully. He has kept it at bay for 25 years by sticking to what he calls “a traditional lifestyle,” continuing to fish, which he does commercially, and keeping active in his church, Henry Fiddler Memorial United.

McDougall’s nephew Clarence, the transportation co-ordinator for the Garden Hill nursing station, also has diabetes. Clarence is 54 and thin as a rake. He has established a regimen where he spends every evening at the Wa-Wa-Tay Fitness Centre, two tidy and spotlessly clean rooms in the local high school filled chock-a-block with exercise equipment set up by the local Aboriginal Diabetes Program. Clarence also makes it a point to eat his vegetables, “even if I have to swallow quickly to do so,” he laughs.

You may unsubscribe from any of our newsletters at any time.

But the McDougalls are the exception. “Diabetes is killing us,” is the blunt assertion of Eric Wood, manager of the local community health program. Murdo and Clarence are controlling their diabetes through exercise and nutrition. Failure to control, though, produces devastating consequences. In the nursing station where Wood has his office, an entire wing has, since 2004, been given over to seven dialysis machines.

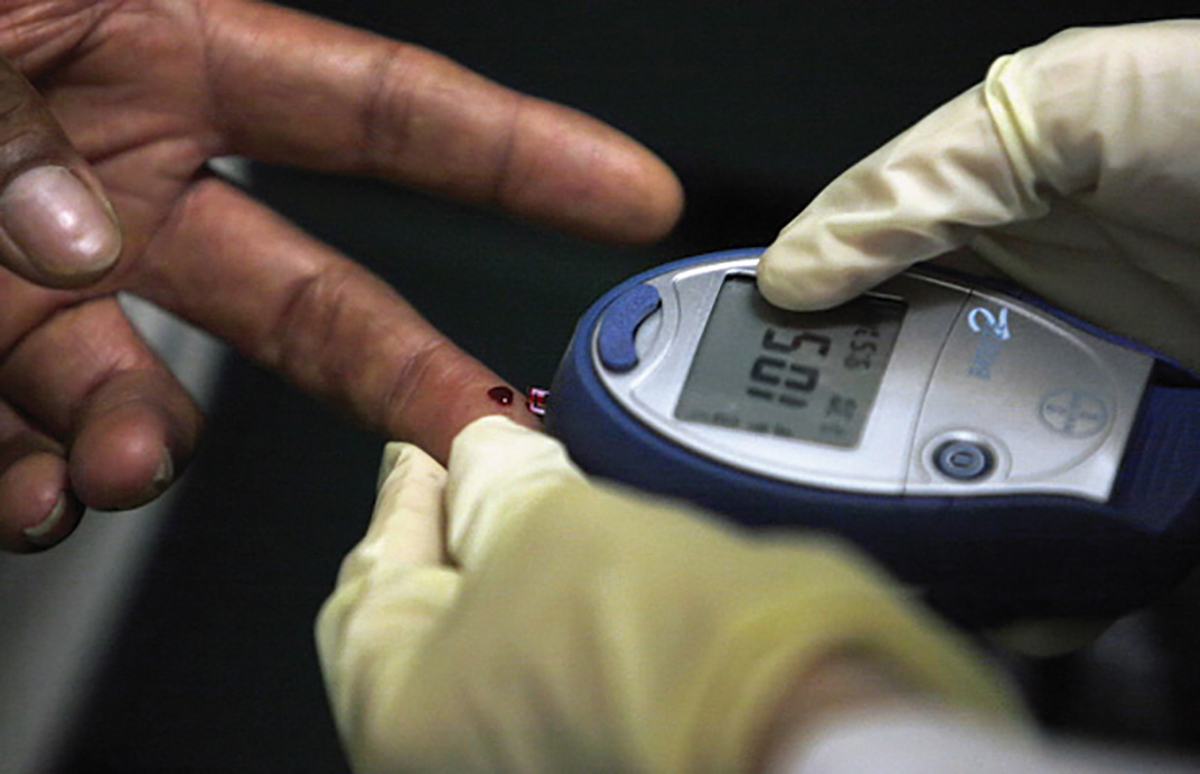

A lot is known about diabetes at Garden Hill. A decade ago, it was one of five First Nations to be studied intensively by Dr. Stewart Harris of Western University’s Schulich School of Medicine and Dentistry. In Harris’s 2010 report, 323 among the 3,000 people in Garden Hill were listed as having the disease. The average age of diagnosis was 40.6; 34 percent of the diabetics suffered chronic kidney disease; 11 percent had coronary artery disease; eight people were on dialysis; eight had suffered amputations of lower limbs; and four had gone blind.

During my visit this past spring, Larry Wood, the local Aboriginal Diabetes Initiative worker, told me that all the stats have gone up. The number of Garden Hill residents diagnosed with diabetes has now grown to 470; the age of onset has dropped ever younger; and 25 (or 43 if the three neighbouring reserves are included) are now on dialysis.

It is hard to put a positive or even hopeful spin on what diabetes is wreaking among First Nations across Canada. The situation can really only be framed as a scourge comparable to the plethora of other afflictions — medical, social and cultural — that have befallen Indigenous peoples since European contact and colonialism.

About 640 million people have diabetes worldwide, prompting the United Nations to call it “a global threat” and some media outlets to dub it “a tsunami.” Never mind that the disease has been around for a long time. About 3,500 years ago, Egyptian physician Hesy-Ra listed remedies to combat “the passing of too much urine.” For a few millennia, contracting Type 1 diabetes was a death sentence. Then in 1923, Dr. Frederick Banting and three other Canadian medical researchers discovered ways to make extracted insulin available for injection.

A few decades later, scientists distinguished between Type 1 and Type 2 diabetes. In Type 1, the pancreas fails to produce insulin — without injections, the patient would die. In Type 2, often associated with obesity or aging or both, the pancreas either produces insufficient insulin or the body struggles to put it to proper use. Type 2 diabetes can be controlled through strict lifestyle interventions such as exercise, weight loss and nutrition. Failure to control it can result in things like blindness, limb amputations and kidney failure (requiring dialysis or a kidney transplant). People in their 60s and 70s are at greatest risk for contracting the disease, though diabetes diagnoses have been on the rise for children in Canada since the 1980s.

For reasons that specialists are still working to understand, some population groups are at substantially higher risk. A 2014 study by the U.S. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention confirmed what has been common knowledge for about three decades: that Type 2 diabetes is found in much higher concentrations among Native Americans, African Americans and Hispanic Americans. Forty percent of Arizona’s Pima Indians have diabetes — the highest rate in the world.

There are all kinds of surveys and statistics. Among the more jarring facts is that in Canada, seven percent of Indigenous women over the age of 15 have been diagnosed with diabetes, compared to three percent for the rest of the female population, according to Statistics Canada. The rate of diabetes increases with age: 24 percent of Aboriginal women over the age of 65 have diabetes compared to 11 percent for the rest of older women in Canada.

Until about 1950, Type 2 diabetes was rare among Canada’s Indigenous peoples. Since then, it has increased to about double the national rate, and in some communities, it has reached three to five times the average. (Type 1 diabetes remains rare among Canada’s Indigenous peoples.) Winnipeg’s Dr. Michael Moffatt, who began his career in the 1970s among the Cree of northern Quebec and the Dogrib of the Northwest Territories, recalls no cases of diabetes at all when he was a young physician. Later, when he became head of Manitoba’s Northern Medical Unit, supervising hospitals in Churchill, Norway House and Rankin Inlet and overseeing fly-in doctors to isolated First Nations, “I started encountering it everywhere.”

A big question is: why? One theory, widely circulated for a time, had a genetic basis. The hypothesis, called “thrifty gene,” held that over thousands of years living off the land, Indigenous hunters had survived cycles of famine and feast by facilitating efficient fat storage during times of abundant food. In modern times, however, abrupt lifestyle changes and the abundance of food — particularly high-fat, high-sodium processed foods — render that genetic trait a disadvantage. For people already predisposed to relative hyperinsulinemia, upper body obesity, insulin resistance or beta cell exhaustion with impairments in insulin secretion, adding an unhealthy diet and a lack of exercise can pave the way toward diabetes. There is resistance in some quarters to any explanations based on genetics or race. However, most scientists accept that genetics and ethnicity play some role.

Many of these lifestyle changes are the result of colonialism. The report of the Truth and Reconciliation Commission argues that residential schools caused social problems that have led to health disparities. For many First Nations, being sent to residential school marked the first time their diets changed drastically — typically from wild food to meals high in carbohydrates. Murdo McDougall adds that Garden Hill families stopped planting their own crops when the community switched to a cash economy (with family allowances) and children, who would otherwise have helped tend the gardens, were sent off to residential school. The community store, at that time still run by the Hudson’s Bay Company, became the predominant source of food, including junk food.

Where people have stuck to their traditional lifestyles, outcomes have been different. Dr. Jim Carson, another Northern Medical Unit doctor, tells the story of a 40-year-old Inuit man suffering from the disease when he was observed in late summer. “He went off on his trap line, returning in the spring 40 pounds lighter and diabetes-free. The coke, candy bars and chips of his sedentary existence had been replaced by ‘country food’ — wild game and broth soups — and the exercise of his trapping work.” The Pima Indians of Arizona have the highest rates of diabetes, while their cousins across the border in Mexico, who have stuck to a more traditional existence, have numbers that are in line with non-Indigenous populations.

Diabetes in First Nations people has been the concern of Western University’s Dr. Harris since he was a young graduate in the 1980s and based in Sioux Lookout in northwestern Ontario. One of the First Nations in his territory, Sandy Lake, now has a 35 percent prevalence of adult diabetes. Harris points out though that during his working life, not only diabetes but all chronic diseases have shown an up-tic. “Massive change to the lifestyle and environment unmasked or facilitated the emergence of cardiovascular disease. Cancer rates are skyrocketing in First Nations populations.”

Diabetes is an expensive disease. The Lancet and PharmacoEconomics recently estimated its annual cost at $1 trillion. In places like Garden Hill, health care is the biggest industry. So many people required dialysis — and had to go so far to obtain it — that the provincial government paid $5.2 million for its dialysis unit. Patients from neighbouring reserves, St. Theresa Point, Wasagamack and Red Sucker Lake, fly in and out for their sessions by helicopter.

When I visited, I learned that the dialysis unit was mandated to support 18 patients. That turned out to be not enough. Twenty-five are on a wait-list and have had to move to Winnipeg to obtain their treatments there. It costs between $95,000 and $107,000 a year to provide a patient with dialysis, not to mention the costs to treat the many complications of the diabetes — vascular problems leading to amputations, nerve damage, blindness. Though not all of the nearly 500 people with diabetes in Garden Hill are in need of expensive levels of care, ultimately many of them will be. Recruiting and keeping trained staff for the dialysis unit is an ongoing challenge, as is finding a secure system of reliably pure water. The unit is periodically shut down as a result of chronic water quality issues.

Along with the economic costs of diabetes come social and psychological costs. The disease disrupts families, stirs anxiety, causes physical suffering, and shifts a patient’s energy and activity away from family and the community and toward his or her own health.

And diabetes isn’t the only problem facing Garden Hill. The community has all the challenges we’ve become used to hearing about from isolated First Nations. It depends on winter roads to bring in supplies, and warm weather this year rendered the road chancy. The band government is in financial default and under third-party management. Unemployment is high, and disaffected youth have formed at least two gangs.

Frances Desjarlais has been working on diabetes for her entire career. The First Nations woman trained as a nurse 30 years ago in her home community of Swan River, Man. Desjarlais, since 2007, has been regional diabetes co-ordinator for Health Canada’s First Nations and Inuit Health Branch in Winnipeg. Her job is to oversee and support 64 local diabetes workers (like Garden Hill’s Larry Wood) on every Manitoba First Nation, as well as meet regularly and provide encouragement and resources to the diabetes co-ordinators of Manitoba’s seven tribal councils. The objective for the next 10 years, she says, is to “slow down the rate of complications, lower diagnosis rates. It’s going to take a long time, but we need to see those numbers.”

When Desjarlais herself was diagnosed 13 years ago, she recalls, “I was floored.” The shock made her understand the predicament of her patients. “Because of my nursing background, I have more information than the normal person. But when you’re living with diabetes, you have all the same emotions; the fact that I’m a diabetes educator doesn’t mean squat. I knew I was going to have to live with this, adjust my diet, learn moderation — that’s a big word for me now — get past my ‘woe is me.’” She started walking every day as a regimen of exercise.

Many of those living with diabetes in Garden Hill, along with the family members and health workers who support them, are getting past the “woe is me” to find solutions that will improve everyone’s health.

Through the Aboriginal Diabetes Initiative and the efforts of its employee, Larry Wood, the Wa-Wa-Tay Fitness Centre is fully equipped. Provincial government funding was used to erect a barn for the community to raise a thousand chickens and to purchase tillers and seeds to grow community gardens. Grade 10 students have become mentors to Grade 4 kids, working with them to get exercise and prepare healthy snacks. The local Northern Store is in the fourth year of using federal subsidies to lower the prices on perishable foods such as milk and fruit. At neighbouring St. Theresa Point, health workers arrange cooking classes, walkathons, nutritional bingos and initiatives to bring nutrition awareness to the local store. It is all positive and all desperately timely.

Desjarlais, like Murdo McDougall, believes there also needs to be a return to emphasis on the land, Native medicine and cultural wholeness. “Aboriginal people need to look at our teachings and traditions of caring for ourselves, care for our bodies,” she says. “We need to take back our Indigenousness, go back to our gardens, back to the land as when we were healthy. When we worked hard and our kids played outside instead of couch surfing, we were healthier. Processed food, smoking — we need to step back and see what we can do. This isn’t just one thing, diabetes, this is everything. We need to work with families and elders. It’s going to take us a while, but we need to do that.”

Looking into the future, it takes courage to see beyond more expenses, shortened lives and misery. Fighting diabetes among Indigenous people will require constant vigilance along with the sense that victory, though slow, is possible.

This story originally appeared in the July 2016 issue of The Observer with the title “The disease of colonialism.”