The minute Nadine Green spots me for the first time, she smiles and opens her arms for a hug. Green is the site coordinator at A Better Tent City, a community of private cabins in Waterloo Region, Ont., that provides temporary shelter for about 50 people experiencing homelessness. Established in April 2020, in the grip of the pandemic, it’s the first of its kind in Canada.

We arrive at a portable that contains a fully stocked kitchen, living and dining room and a few other amenities. Behind us, nuns are sorting through piles of donated clothing, while community residents chat with one another. A woman living in the community asks Green if she can look through the clothes, but Green tells her not yet; anything her size will be sent her way. This isn’t the only time Green has to excuse herself to address a question from a resident or volunteer. She’s busy.

You may unsubscribe from any of our newsletters at any time.

Green was a convenience store owner who opened her business at night to create a safe indoor space for people to sleep. Over time, the store became more like a shelter, and she began sleeping in her store so that she could supervise the space around the clock. The building’s landlord eventually evicted her from the store, but media attention around what she had been doing was the catalyst for philanthropist Ron Doyle, a local business leader, to found A Better Tent City. Doyle, who died in 2021, was the project’s first landlord. Green collaborated with him and with former city staffer Jeff Willmer, along with other like-minded supporters, to get the project going.

At times, it’s been a struggle. “[People] don’t want you to move beside their business. They don’t want you to move beside their houses, in their community,” Green says. “I believe maybe they just want people to not exist. Once you’re homeless, they just don’t want you anywhere.”

Green speaks from experience. Not only has she been working with A Better Tent City since its inception, but she has also experienced homelessness herself — first in her late teenage years and again, briefly and by choice, after being evicted from her store.

Though cabin communities were unheard of in Canada only a few years ago, they have recently started appearing across the country, from British Columbia to New Brunswick. And cabin communities aren’t the end of it. Throughout Canada, other signs of change are emerging, bringing with them hope that systemic fixes might be possible.

Some of these changes have been in the policy and legal worlds. Recent Ontario court rulings in Waterloo and Kingston have cemented into law that people experiencing homelessness cannot be evicted from encampments when there’s not enough shelter space to house them. In Toronto, after violent encampment clearings in the summer of 2021, a new encampment strategy has been unveiled that claims a human rights approach.

The world of advocacy is changing too. People experiencing homelessness have taken a greater lead in political activism and community support through organizations like the Hamilton Encampment Support Network and the Toronto Underhoused and Homeless Union.

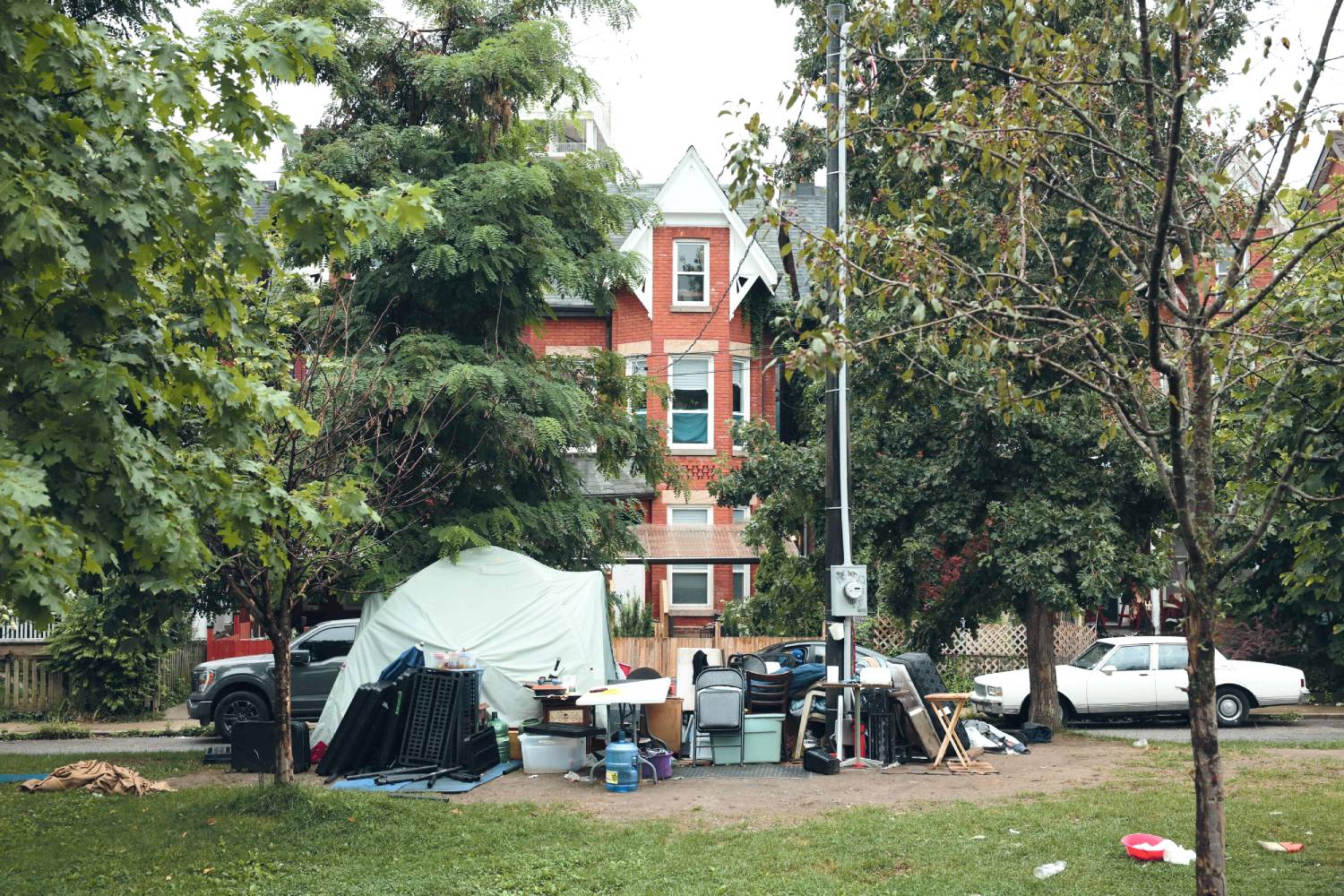

But these shifts do not change the fact that homelessness in Canada is rapidly increasing. The country was already struggling to support its unhoused population when COVID-19 hit. Since then, homelessness, an epidemic of its own, has spread. Shelters are overflowing in many cities. Of the 71 respondents from 68 Canadian communities Statistics Canada polled in 2022, 80 percent said the number of encampments in their communities had increased since the start of the pandemic. Three-quarters of respondents also said more people lived in each encampment.

Ontario alone was home to at least 1,400 encampments as of 2023. Last year, over 80,000 people were homeless in the province according to the Association of Municipalities of Ontario, a 25 percent increase from 2022.

So are these brave new strategies to address homelessness making any difference at all?

Homelessness is a fiendishly complex problem. It plays out in municipalities, but they rarely control all the policy levers to solve it. Take Toronto, whose sheer size makes it a case study for the rest of the nation. Toronto city councillor Alejandra Bravo cites the opioid crisis, lack of available mental health care, increasing rents and evictions, a growing number of refugee claimants and decades-old federal policy decisions as factors that have compounded the current crisis. The city often relies on funding from other levels of government to build affordable housing and other supports — which they may or may not receive, Bravo notes.

The situation in Toronto is so dire that in 2023, the city declared homelessness an emergency. As of fall 2023, more than 12,000 people sought a shelter bed in the city each night, a 60 percent increase from the roughly 7,300 people reported to be experiencing homelessness in 2021. About four in 10 shelter residents were refugee claimants.

When homelessness explodes, encampments follow, typically materializing as groupings of tents in public parks. Some people gravitate to encampments because the rules and restrictions of shelter living are incompatible with their lifestyles — perhaps because they have a pet or want to live with a partner or use substances. For others, experiences and stories of physical and sexual violence in shelters have made them feel safer sleeping outside. Some call shelters hoping to get a spot and are turned away because there’s not enough space. That happened to about 192 people each night in November 2024 in Toronto, a staggering number compared to the 16 callers a day who were successfully matched to a shelter. (The city’s average nightly shelter occupancy that month was 9,623.)

“Homelessness is a fiendishly complex problem. It plays out in municipalities, but they rarely control all the policy levers to solve it.”

Last May, Toronto responded to its homelessness boom by unveiling a new strategy for encampments and their residents. Called the Interdivisional Protocol for Encampments in Toronto, it emphasizes communication with residents and attention to their human rights.

This new approach evolved in the wake of backlash against three high-profile encampment evictions in 2021 at Trinity Bellwoods, Alexandra and Lamport Stadium parks. The events seared the public memory with images of police in riot gear clashing with residents and their supporters.

City officials, too, now see the 2021 evictions as disastrous — both from a financial and human rights standpoint. As many activists pointed out, the nearly $2 million price tag on these three clearings could have been spent on housing encampment residents.

Toronto’s ombudsman, Kwame Addo, investigated the evictions, finding that the city prioritized “speed over people.” Toronto’s new encampment policy integrates almost all of Addo’s recommendations. It says enforcing bylaws related to encampments is a last resort. Instead, city workers from health, mental health and harm reduction services are to support encampment residents and surrounding communities.

“It shifts away from enforcement and clearing, which we know only moves people from one place to the next and hasn’t worked as an approach to encampments,” Bravo says. “This is an important step.”

But many have criticized the new protocol for not going far enough. For example, the policy specifies that the city can still evict encampment residents with little to no notice.

To Alexi White, the director of systems change at Maytree, a national organization based in Toronto that takes a human rights-centred approach to ending poverty, it’s plain that more needs to be done. “[I] see this change as an important improvement to a policy that will — that must — continue to improve over time.”

Rev. Angie Hocking is a United Church community minister who helped found the Toronto Underhoused and Homeless Union in 2023. She says the new protocol is “better than violent clearings, for sure,” but is disappointed that it emphasizes preventing encampments. To her, that’s eviction by a different name, because people who are prevented from setting up tents still have nowhere to go.

Hocking has worked with many former residents of the Allan Gardens encampment, where Toronto’s new approach was piloted in summer 2023. When new people tried to join the encampment, Hocking says, city officials were there around the clock to turn them away, preventing the encampment from growing.

In fact, despite the rights-based framework of the new protocol, one of its key goals is to make sure public spaces are available to everyone and that encampments do not become entrenched, Gord Tanner, general manager of Toronto Shelter and Support Services, told a city committee meeting last May.

Allan, who arrived in Canada in December 2022 as a refugee from Uganda, is part of the emerging trend across Canada to bring the voices of those experiencing homelessness into the conversation. As a volunteer with the Toronto Underhoused and Homeless Union, he does outreach work for the union educating people about their rights. But he also educates the public by telling his own story. (His last name has been omitted for safety reasons.)

He tells me that he slept in bus stops for days after arriving in Canada before winding up at a men’s shelter in downtown Toronto. There, he experienced repeated sexual abuse, but he says the shelter refused to relocate him — even to a different room — citing lack of space. After a life-threatening attack and two days in hospital, he finally got space in a different shelter. Still, he struggled to find housing and often felt he was without support.

Many of his experiences are specific to his identity as a refugee. His attacker at the first shelter made derogatory racial and cultural comments toward him. At the second shelter, he found that as a newcomer he didn’t know his rights. A shelter worker repeatedly threatened to evict him; he was unaware her threats weren’t credible.

Allan’s tale is technically one of success. He has found housing and work as a drop-in relief worker at a church. But he has been in Canada for about two years and has only been employed for the past few months. The rest of that time was spent struggling and searching. It astounds him how little people know about experiences like his. An Ontario MPP came to a union meeting and listened to members’ stories. Allan recalls her reaction: “She [said], ‘Really? Do these things happen here in Canada?’”

That’s why Allan serves on the executive committee of the Toronto Underhoused and Homeless Union, the group Hocking helped found. He says that change won’t happen until people open their eyes to homelessness instead of looking away. “You, people who are in corporate offices, come back down to people who are down on the ground,” Allan says. “Find out what touches them, find out what challenges they go through.”

The union, which is affiliated with the National Union of the Homeless, a movement born in the United States, helps people in day-to-day ways, too, Hocking says. For example, it sent a letter to a shelter that was denying its residents food after sunset, making it impossible for them to fast for Ramadan and Lent. Residents wrote addenda to the letter describing being told by staff that “it doesn’t matter if something’s halal” or that the shelter wouldn’t save meals for them after sunset because “it’s [their] choice to fast.”

The union, Hocking explains, gives people experiencing homelessness the collective power to voice these kinds of complaints. On their own, people often feel too vulnerable to stand up for themselves. While we’d like to think that self-advocating would never affect someone’s shelter, “sadly, it can,” Hocking says. “It can affect their stability. But even if it wouldn’t, people don’t want to risk that.”

The group also offered self-defence classes to residents of the Allan Gardens encampment who were being attacked at night. Residents feared calling 911 for help in case police evicted them from the camp, Hocking says. The self-defence training is “not addressing the fact that people don’t have a home, but it is addressing, perhaps, sleeping a bit better that night, and perhaps that means that their mental health will be feeling a little bit better, and that means that they might go to that doctor’s appointment,” she says. “There’s actually all these ripple effects about feeling safer and being safer.”

***

In Canadian courts, legal approaches toward homelessness and encampments have also shifted. Recent rulings have sought to redefine how society understands encampments, grounding the arguments in the Canadian Charter of Rights and Freedoms.

Rights-based understandings of housing in Canada are rooted in the Universal Declaration of Human Rights, but it wasn’t extensively codified until 1976 when Canada signed the International Covenant on Economic, Social and Cultural Rights. It’s a United Nations human rights treaty that recognizes, among many other things, the human right to housing. Every province was involved in Canada’s decision to sign, explains Maytree’s White.

Nearly 50 years later, that’s still a dream. Encampments themselves are proof that the right to housing has not been realized for all Canadians. At the same time, White says, “if you’re unhoused, and you set up a tent somewhere, that is, in a sense, a claim on the right to housing.”

Encampments create legal obligations for governments under international human rights law. “One of the big ones that obviously we spend a lot of time talking about is the right not to be arbitrarily evicted,” White says.

Over the past few years, Canadian courts have begun protecting this right. In 2023, an Ontario Superior Court judge in the Region of Waterloo ruled that encampment residents had the right to set up tents outside if enough shelter beds weren’t available. The Region of Waterloo chose not to send this decision to the Court of Appeal, meaning that the ruling is legally binding in Ontario and is persuasive in other jurisdictions. A Victoria court made a similar decision back in 2008.

Some municipalities have criticized these court rulings. In October, mayors of 13 Ontario cities wrote to Premier Doug Ford asking for legislative changes — including use of the notwithstanding clause if necessary — to “help municipalities with issues related to mental health, addiction, and homeless encampments.” The clause allows legislation to stand even if it violates certain rights protected by the charter. If invoked to protect local bylaws that ban encampments, the notwithstanding clause could undermine the 2023 ruling in Waterloo.

The Ford government has not invoked it. Instead, it allocated $75.5 million to support affordable housing projects, temporary housing and other programs. And in December, it introduced an act that imposes jail or a fine of up to $10,000 on those found guilty of using illegal substances in public, allowing for immediate arrest. For encampment residents struggling with addiction, using substances in private spaces is rarely an option, nor is the ability to pay steep fines. (British Columbia tried to enact a similar law last year, but it failed due to resistance.) Ford has said that he doesn’t expect to use the notwithstanding clause to enforce the new act but will consider it if he needs to. City councillors, advocates and lawyers have raised concerns about that possibility.

More on Broadview:

Even without the complication of the notwithstanding clause, the law is unclear on plenty of other issues. In both Ontario and British Columbia, encampment evictions are only ruled out when residents do not have access to adequate indoor shelter space. But what is considered access? What kind of indoor spaces are considered adequate? And how might those definitions consider — or not consider — people’s individual needs?

A proposed amendment to the rules in Vancouver in 2023 attempted to codify a definition of “reasonably available alternative shelter” when municipalities are trying to evict encampments. Reasonable shelter was defined as “a staffed place where an individual may stay overnight, and have access, either at, or nearby the shelter to a bathroom, a shower, and an offered meal.”

Both municipalities and activists took issue with that. For many municipalities, these provisions seemed lofty and unattainable, making it too difficult for them to evict encampments if needed. For activists, they seemed too sparse, making it too easy for municipalities to carry out evictions and to house people in unsuitable conditions. The amendment did pass in 2023, but in July 2024, the provincial government reached out to municipalities to let them know that it would no longer be enforcing the legislation.

And it only gets more complicated. Not evicting people from encampments is the bare minimum that a government can do to recognize the right to housing, White says. Governments also have responsibilities to provide things like clean water, sanitation and cooking facilities to help people attain their right to adequate housing. They can also work to honour people’s rights by actively engaging encampment residents in conversations about their housing needs.

“Are [cities] having real conversations in the way they would if it was, you know, a homeowner down the street, with the same kind of level of respect and the same kind of recognition of people’s personal capacity to make decisions for themselves?” White asks.

***

Back at A Better Tent City, the culture is slow-paced and hopeful. “If you’re in a hurry, this is not a place for you to be,” says Green. She has been living at A Better Tent City since 2020 so she can be on hand to support residents whenever they need her.

The community has bathrooms, showers and laundry facilities. That means health and hygiene benefits for the 50 or so residents. But the cabin community cannot help everyone with everything they may need.

For example, not all visitors can use the showers. When the two individual shower rooms were first installed, non-residents tried to move themselves and their belongings into them, drawn by the warmth and the privacy, Green says. These days, a resident holds the shower keys for the whole community, and anyone wanting to shower must sign out a key.

It’s difficult to balance quality and quantity of support, a problem of competing priorities that’s playing out across the country’s homeless organizations, most of which are underfunded and stretched thin. A Better Tent City’s community knows what it’s like not to have anywhere to go. In improving the lives of some, they’ve made the hard choice not to house others.

Not only that, but while A Better Tent City opens its arms to anyone who would like to eat, drink water and visit with the community during the daytime, there are no plans to build more cabins. Existing cabins rarely become vacant. Although a few of the community’s original residents have moved on to permanent housing, many have remained for fear of isolation or failure, says co-founder Jeff Willmer. It means A Better Tent City is at risk of turning from a temporary solution into a semi-permanent one.

“We find it is difficult to have people move along to the next step,” Willmer says. “I don’t know if that’s a good or a bad thing that we’ve provided this sense of community and family that many people need.”

Certainly, the residents I met highlighted how much they value A Better Tent City. Diana Myers described it as “like a family.” Within community borders, there is no urgency to move people along. “Check your hurry outside before you come in,” Green says. But outside, in the context of a national homelessness crisis, there is a lot of hurry. And there is an urgent need to house as many people as possible.

***

If homelessness is booming but so is change, what does that mean for the future? If these years since COVID-19 have been pivotal, in what direction are we pivoting?

I find myself pondering these questions as I take a final walk with Green through A Better Tent City. She points out her house to me — a pale yellow structure with a heart spray-painted on the side — and asks if I want to take a photo of her standing next to it. I enthusiastically agree.

Green’s work and her life have coalesced into a single purpose: helping others in the present. “We take care of the now, and after will come after,” she tells me. Clicking my phone camera, I am struck by the love and compassion Green feels for her community. It makes me feel hopeful.

But it would be foolish, I think, to feel optimistic for the whole messy system. After all, one woman’s love and compassion alone can’t secure the right to housing in Canada.

For activist Greg Cook, the only real cause for optimism would be the implementation of a comprehensive strategy to provide more affordable housing. He wants cities to build things like social housing, rent-geared-to-income housing and co-ops, but doesn’t see this happening anytime soon. In fact, everywhere he looks he finds systemic barriers. “Because things like pensions are privatized much more, and people rely on home ownership … there are literally hundreds of thousands of people in Canada — middle class people — who don’t want the value of their house to go down, and so [they] like the high cost of housing,” Cook says.

Lynn Walker, a former resident of the Allan Gardens encampment, echoes Cook’s sentiment that investing in housing is the most important thing a city can do. “Proper housing,” she says. “Not modulars. Not little, tiny places where you’ve got this room that’s like a jail.”

And yet, immediate solutions matter too. The Toronto Underhoused and Homeless Union is one piece of the puzzle. A Better Tent City is another. As I click the camera and feel Green’s warm smile spreading to my own face, I know she’s making a difference for a group of people in the community who would otherwise be sleeping on the streets.

Interventions like these are not nothing, but they are also not enough. As we are swept further into the homelessness crisis, will these winds of change gather the strength to push us in the other direction? Or will they fade, leaving us adrift?

***

Amarah Hasham-Steele was an intern at Broadview last summer. She is now doing a master’s degree at Trinity College Dublin.

This article first appeared in Broadview’s March 2025 issue with the title “Rethinking Encampments.”