It was by accident that Jason Tarshis learned the truth about his origins. At 49, he bought a home genetic test kit, mostly to keep his wife company as she searched for a brother who had been adopted as an infant. Her results soon led her to her long-lost sibling. But his results were puzzling.

According to the genetic test company, Ancestry, his ethnicity was half-British, but his DNA was connected to a British family he didn’t know. They seemed to be Anglican, and Tarshis had grown up Jewish.

You may unsubscribe from any of our newsletters at any time.

His father, a dentist, had died at 47 of pancreatic cancer, and over the years, Tarshis had drifted out of touch with his paternal side. But now he reconnected with them. His father’s older brother admitted the family didn’t know much about Tarshis’s grandfather, who’d immigrated to Canada on his own from Russia. Intrigued by the mystery, Tarshis and his uncle met up and started digging.

Tarshis mentioned the confusion to his mother as well and asked if she knew anything. Normally a woman to talk, she went kind of quiet, Tarshis says, and told him she didn’t. He says he tends to take people at their word: “When my mom says she doesn’t know, I just figure she doesn’t know.”

Tarshis told his sister about the findings too, and she agreed to take a genetic test as well. A few weeks later, the results revealed that the siblings had different fathers. Tarshis didn’t know what to make of it.

He went back to his mother. He told her that he’d discovered something strange and wanted to talk to her about it in private. It took a while, but eventually his mother told him that she’d gone through “treatments” and that those “treatments” were inseminations: a doctor had taken sperm from an anonymous donor and placed it into her body. There was no way to find out who the donor was.

Except, Tarshis realized, maybe there was.

After learning about his sister, Tarshis had gone back to the Ancestry website and plunged obsessively into the files it contained. There were photos, family trees and family names. They led him to obituaries and official records. He took all that information, including the surname that seemed to be connected to him, and he began an intensive online search. It turned up a photo of a man that made him pause.

“I’m looking at this picture, and I see the outline of this man’s ear,” says Tarshis. “And I’m like, ‘That’s my ear.’”

The man and his family looked eerily similar to Tarshis and his family. He could no longer deny they were related. Yet it felt strange. “It was like being in a soundproof glass room, where you only have one-way glass. I can see out, but they can’t see in. And I know everything about these people, and they know nothing about me. I don’t even exist to them,” he says. “It was the most lonely feeling you can imagine.”

Next to the man’s photo was a phone number. Tarshis called it, hoping for a recorded message, to hear the man’s voice. The man himself answered. Tarshis found himself asking if the man had been a medical student at the University of Toronto and if he’d ever, perhaps, donated sperm. The man said he had. Then the man brought his wife onto the line.

She was warm. She said her husband had told her he’d donated sperm, and she’d encouraged him to do genetic testing in case anyone was out there looking, but he hadn’t. Tarshis was the first offspring to be in touch. “This must be really hard for you,” she said. And then: “We just want you to know that we like family —and we can always use more.”

***

Back when Tarshis was conceived in 1969, sperm donation was a local affair. Doctors promoted it to their students as a charitable act, for pocket money. Tarshis’s biological father described getting phone calls saying he was needed, then hurrying over to the clinic to donate. Donors would go up the fire escape, he said, to avoid crossing paths with patients.

The sperm would be provided to a patient who was scheduled to be in the office that day. Back then, patients were all married women whose husbands had fertility problems. After the sperm was syringed into the woman’s body, she was told to go home, have sex with her husband and forget about what had happened in the office. The couple was counselled never to tell. Tarshis’s mother dutifully kept the secret for half a century.

There was a widespread feeling that both families and donors deserved privacy. Even the idea of sperm donation had to be kept quiet: people worried that it could destabilize the legal family unit, and also that men wouldn’t agree to donate if it meant being identified.

It wasn’t until the 1980s and ’90s that doctors started inseminating single and lesbian women who wanted to be parents. These novel types of families brought new openness. Solo and same-sex moms had to explain where the sperm had come from, and with none of the shame of infertility and no father who risked humiliation, they did: it was sperm donation.

These new family structures also fostered new beliefs about what made a family. Families were built on love, not blood or genes. Families could be chosen. The concept of using a sperm donor became less taboo, and the concept of anonymity less fraught: if genetics didn’t matter, who needed to know who the donor was?

Meanwhile, the fertility industry was also changing. In 1996, Canada brought in what became known colloquially as “the semen regs” to make donor sperm safer. Men providing sperm now had to be tested for HIV and other sexually transmitted diseases before they donated. Their sperm then had to be frozen and held until the men were tested again six months later. Only after two disease-free tests six months apart could the sperm be released for use. But doing all that was expensive and time-consuming, so many clinics didn’t. Health Canada ordered them shut down.

More on Broadview:

Canada’s sperm business never recovered. These days, there are only two commercial sperm banks in the entire country, offering anywhere from a dozen to about 30 donors at any given time. The result is that more than 90 percent of the sperm used in Canadian inseminations is imported, mostly from the United States and Europe. Gone are the days of sneaking in back doors; now men enter into annual contracts with sperm banks that keep their semen in the freezer until someone orders it from an online database. It can be shipped anywhere in the world.

It’s anyone’s guess how many sperm donations take place in Canada each year. According to the Canadian Fertility and Andrology Society, a group that represents professionals working in the fertility industry, no one keeps track of the ones that take place in medical facilities. And not all sperm donations happen through official channels in any case. Some donors offer their sperm directly to friends or acquaintances. Other donors connect with would-be parents through social media platforms like Facebook, Co-ParentMatch and Just a Baby. Most of those inseminations are done in people’s own homes or in local hotels, and, more often than you may imagine, donor sperm is passed through car windows in coffee shop parking lots.

So much had changed in Canada in the 50-plus years since Tarshis’s mother sought help to have a baby. But one thing had not really changed: the assumption that a donor should have the right to remain anonymous.

***

That Canada would be a holdout, protecting donor anonymity, was not at all a foregone conclusion. In fact, early in the process of crafting our law on assisted reproduction, an all-party parliamentary committee on health recommended the opposite. In a December 2001 report, the committee wrote: “We feel that, where there is a conflict between the privacy rights of a donor and the rights of a resulting child to know its heritage, the rights of the child should prevail…We want to end the current system of anonymous donation.”

They argued that donors, as a condition of donating, should have to consent to being identified and to making their medical information available. Donors deserved counselling, the committee said, to understand what they were getting into. As for the people born via donation, they deserved not only to know who the donor was, but also to have a way to connect with half-siblings born through the same donor, if for no other reason than to avoid incest. In return, donors should be protected from any financial or parental obligations.

The ideas were forward-thinking for the time, but they did not make it into our law. When Canada’s Assisted Human Reproduction Act (AHRA) came into force in 2004, the law said that “the identity of the donor — or information that can reasonably be expected to be used in the identification of the donor — shall not be disclosed without the donor’s written consent.” Donors would remain anonymous.

Meanwhile, in many parts of the world, the view on anonymity was going the other way. Years before our assisted human reproduction law passed, Sweden, Austria, Switzerland, the Netherlands, Norway and the state of Victoria in Australia had already passed laws requiring the donor to be identified when the child turned 18. In 2005, the United Kingdom followed suit.

In the United Kingdom, for instance, any person conceived via donated sperm or egg after April 1, 2005, had the right when they reached age 18 to know the full name, place of birth and last known address of the donor. Even before that, at age 16, offspring could learn non-identifying details, such as eye colour and ethnicity. The change in the U.K. law came about after two donor-conceived people took their government to court, arguing that the law as it stood violated a section of the European Convention on Human Rights.

In 2008, Canada faced its own court challenge in British Columbia from 26-year-old Olivia Pratten. As a teenager, Pratten had given testimony to parliamentarians during the making of Canadian law. “Sometimes when I’m in Vancouver, I wonder whether I pass him on the street,” she told them. “When I meet someone who was a UBC [University of British Columbia] student around the time I was conceived, I look him over and wonder, could he be my biological father?”

Now in her court challenge, she was arguing that donor-conceived people like her had a right to know their origins and deserved protections equal to what adopted people in the province enjoyed. B.C. laws recognized that adopted people had legitimate questions about their origins and so required that such information be gathered and preserved for them. Treating donor-conceived people differently, Pratten said, constituted discrimination under Section 15 of Canada’s Charter of Rights and Freedoms.

In May 2011, the B.C. court agreed. The judge gave the province 15 months to update its laws. It was the first ruling of its kind in North America, and it looked for a moment as though laws across the provinces and even in the United States might change.

But in 2012, the B.C. Court of Appeal reversed the decision. It ruled that there was no constitutional right to know the identity of your parents and that the special protection provided to adoptees was to help a group that had been historically subject to “negative social characterization” and deliberately separated from their biological parents by the state. The Supreme Court of Canada declined to hear Pratten’s case. And that was the end of that.

Change continued elsewhere. Over the years, Croatia, Finland, France, Germany, Ireland, Lithuania, Malta, New Zealand and the other states in Australia all made changes to their laws that, in one way or another, made donor anonymity a thing of the past. In 2022, the state of Colorado became the first U.S. jurisdiction to pass a law promising to bring anonymous gamete donation to an end.

And then, almost unnoticed in the rest of Canada, Quebec changed its law too. According to an amendment to the province’s civil code, anyone conceived in the province from donated sperm or eggs from June 6, 2025, onward will have the right to know the identity of the donor when they turn 14, or even younger with parental consent. Donors can still veto contact, but they can’t veto being identified.

The disclosure will include the donor’s full name, age, ethnicity, education level and profession, as well as details about appearance, personality traits and interests. The precise details of how it will all work are still being ironed out. The registry that will collect and safeguard this information is still being built. But soon, donor-conceived people in Quebec will be able to know their origins.

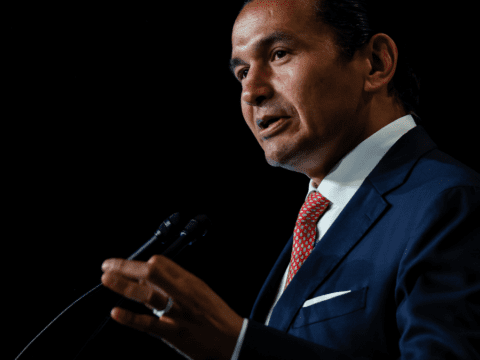

No court case prompted this monumental shift. Instead, says Michelle Giroux, a law professor at the University of Ottawa, it was the culmination of a series of smaller steps. First, there were the years of groundwork by academics — herself and others — making the case for a child’s inherent right to know. Then there was the government-commissioned Roy Report on how to reform family law, chaired by Alain Roy, a law professor at the University of Montreal, and published in 2015; among its recommendations is the right to know one’s origins. Then, in 2022, the Quebec Charter of Human Rights and Freedoms was amended to explicitly say that every person has that right. Finally, in 2023, the family law itself was redrawn to include this right specifically for people conceived though donor gametes, starting two years later.

I asked Giroux if she was hopeful about the law. Was it what she had hoped for? Was it a big win? “Yes,” she said. “Yes.”

***

As Tarshis’s experience shows, the promise of anonymity is meaningless anyway. Cheap and easy home genetic testing makes staying anonymous all but impossible. Even if the donors never take a genetic test — and even if no one in their immediate family ever tests — it’s now fairly easy to use a combination of genetics, genealogy and basic Google searches to trace a path to their door.

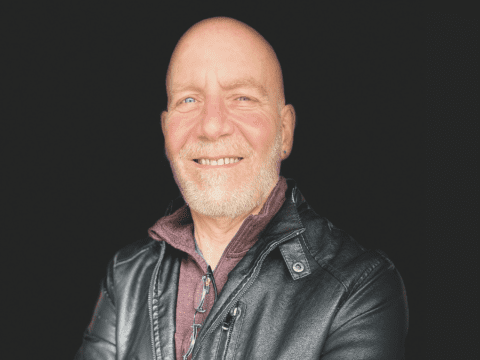

The first time a person ever tracked down an anonymous sperm donor this way was in 2005, and it was a 15-year-old boy from Colorado named Ryan Kramer. Five years earlier, he and his mother, Wendy, had launched the Donor Sibling Registry, an on- line platform where donor-conceived people could connect with half-siblings or donors through the donor identification numbers that clinics sometimes assigned. But Ryan wanted to find more about his sperm donor’s country of origin, so he kicked things up a notch.

He spit into a tube and sent it to a company called FamilyTreeDNA. Genetic testing was not as refined back then, but because Ryan was male and had a Y chromosome, and because Y chromosomes are passed down relatively unchanged from father to son over many generations, much like surnames, Ryan’s Y chromosome was able to connect him with a surname. And that surname, after some sleuthing, led him to his biological father.

I was the reporter who broke that story, and I still remember the dawning realization in many of the people I interviewed, including geneticists and fertility doctors, that the age of anonymity had come to an end. Today, with more sophisticated genetic testing and millions more people voluntarily handing over their DNA, finding genetic relatives is even easier. I used to write about people searching for their donors, but now it’s mostly stories of people finding them.

Sperm banks saw the writing on the wall. In addition to their stable of “anonymous” donors — which many would-be parents still prefer — they began offering donors described as “open identity” and “ID release” and “willing to be known.” The deal was that at age 18 the offspring could be told the identity; however, some banks have shirked that responsibility, according to Wendy Kramer. At the same time, many banks made prospective parents sign contracts saying they wouldn’t go looking.

Kramer, who still runs the Donor Sibling Registry — it now has more than 92,000 members — isn’t impressed with the promise of revealing information when a child turns 18. She believes that making kids wait is harmful. “Nowhere ever in history, anywhere on the planet,” says Kramer, “has anyone deemed it in a human being’s best interest to be kept from their close genetic relatives for the first 18 years of their life.”

Olivia Pratten, the B.C. woman who tried, through the courts, to learn the identity of her biological father, agrees. She is sad that she missed out on all the early years of knowing her biological family. Like almost every donor-conceived person out there looking, Pratten eventually found out who her biological father was. But she was too late. The donor, an American pediatrician, had died in his 60s, 17 months before she discovered his name.

Her feelings of loss were complicated. It was important for her to see his gravesite, so she flew over from the United Kingdom, where she now lives. “It was an instinctive reaction,” Pratten says. “It was like, ‘I’ve looked and looked and looked, and if this ends in a gravesite, I have to go there.’” It was like closing the chapter, she says.

A couple of years later, she also spent a day with the man’s brother, her biological uncle. She says it was important to meet a member of that family in person. At the time, Pratten felt most heartbroken about her biological grandparents. They’d both been alive and well and living just across the river from her when she was a student in New York City in 2007 and 2008. But she wasn’t allowed to know who they were.

“At the end of the day, I’m just somebody who wanted to reconnect with my biological family….I

just wanted to know them,” she says. “Why should I be in that situation to begin with? I shouldn’t be in that situation.”

***

After Tarshis spoke to his biological father on the phone, they discussed plans to meet. Not long after they talked, but before they were able to meet in person, Tarshis himself was contacted by a stranger.

It was a woman of about his age who thought she might be a half-sibling. She had known for years that she’d been donor-conceived, and she’d spent more than a decade of her life searching for, but not finding, her biological father. In fact, finding him was unimaginable to her then. Tarshis was the first genetic close hit she’d ever had.

Tarshis privately suspected, given the amount of DNA they shared, that she wasn’t a half-sibling but a first cousin. One thing he’d learned when he’d spoken to his biological father was that the man’s brother had also donated sperm. But the brother had never told anyone, and Tarshis didn’t want to be the one to betray the secret.

He didn’t know what to do. If he told the woman about his own search, she might want to connect with his biological family and all this would come out. The family might fear a barrage of people and slam the door shut. He decided to wait until after he met the family a few months later. “They’ll meet me. They’ll see I’m not a total nut job. And then I’ll tell them.” So when he met with the woman for dinner, he said nothing about his discovery — even as she shared years of paperwork about her own failed search.

But then COVID-19 arrived, and his meeting with his biological father was postponed.

Tarshis’s biological father had sent him three books containing the family history — biographies, photos, family trees, baptismal certificates, educational histories, travel stories and mentions of ailments. The books had in fact been compiled by the brother. Still Tarshis stayed quiet. “I felt horrible about it,” he says.

Eventually, he did meet his biological father and his father’s wife in person when they were passing through town. They got on well. “I actually felt totally at home with these people,” says Tarshis. Gingerly, he told them about the cousin. A year and a half had gone by since she’d first been in touch. The donor and his wife said they believed that “in time” the brother might come around. But for Tarshis, keeping the secret was extremely stressful. Half a year later, he told them he just couldn’t keep it from his cousin any longer. They gave their blessing for him to tell her. “I was in tears,” he says.

Donor-conceived people find themselves in this sort of conundrum all the time, says Wendy Kramer. Over the years, she has counselled thousands of people trapped in the deceptions, secrets and lies that donor anonymity can give rise to.

Her family faced its own challenges. When Ryan first tracked down and met his biological father, for instance, the man asked the boy to keep his identity secret. As Ryan slowly came into contact with donor siblings, he and Wendy honoured the donor’s request, providing the others only things like photos, medical history and family information, but not the man’s identity.

Eventually, after many years, the donor had a change of heart and was willing to be fully known to all the people — now 30 — he had helped create. But while the others only connected with the man later in their lives, Ryan had had the chance as a teenager to meet him and even get to know the man’s parents as his grandparents.

“It’s this core issue of trying to figure out that very fine line between secrecy and privacy,” says Kramer. “And it’s not easy.” It was not easy for her, she says, and from what she’s heard, it’s not easy for a lot of people. “I think in hindsight, so many people who kept secrets look back and go, ‘Why did I do that?’”

***

Vardit Ravitsky, a bioethicist who is president and CEO of the Hastings Center, a non-profit bioethics research organization in New York, believes that donor-conceived people in Canada have been wronged by not having access to knowledge about their origins. “I’m not saying everybody wants access. I’m not saying everybody cares, or everybody’s harmed,” she says. “But I think people should have the choice.”

Ravitsky laments that Pratten’s case did not go all the way to the Supreme Court, which could have resulted in change across the country. She says she would love to see Canada revisit its regulatory position on anonymity, learning both from other countries who’ve done it and from what we now know from an entire generation of donor-conceived adults telling us what they would like to see.

Giroux believes it will now be up to each province to decide what to do. But if any of the other provinces are taking note of what’s happening in Quebec and thinking of doing the same, she is not aware of it.

So for now, donor-conceived people born in the rest of Canada will have no more right to ever know the identity of the donor who helped create them than do Tarshis or Pratten. The per-

son born today may have parents who chose a donor willing to be known in the future. The person born today will no doubt have genetic tools we can only dream of. But that person will still face a type of uncertainty that people in places with access to donor information will not.

For Pratten, finding out the identity of the donor felt like “a bit of a middle finger to the system,” she says. “I remember feeling like, ‘You told me I wasn’t allowed to know, you told me I had no right to know, and, fuck you, I did it anyway.’”

And that was when it hit her especially hard. She simply could not believe that anyone could ever have thought it was okay to deny her this. “This is my information. This is my identity. I can’t believe I walked around for so long not knowing.”

***

Alison Motluk is a freelance journalist in Toronto who writes mostly about assisted reproduction. She publishes a weekly newsletter, HeyReprotech.