Soleiman Faqiri died on the floor of a jail cell in Lindsay, Ont., on Dec. 15, 2016, just two weeks before his 31st birthday. He had about 50 injuries, including bruises and a gash on his forehead. Faqiri’s older brother, Yusuf, fainted twice at the sight of his body: blue, purple and still. As per Muslim tradition, Yusuf helped wash Faqiri in preparation for burial. Their father, however, couldn’t bear to be there. “My poor, beautiful brother,” Yusuf thought as he kissed Faqiri’s forehead one last time.

Ideally, these preparations would have happened within 24 hours of Faqiri’s death, but his body wasn’t given to his family until a couple of days later, after an autopsy. Ideally, this never would have happened at all. Ideally, Faqiri, who had been diagnosed with a schizophrenic disorder 11 years before, would have been back in his Ajax, Ont., home in the care of his family. Instead, his life ended after just 11 days within jail walls.

You may unsubscribe from any of our newsletters at any time.

Three years later, his family still doesn’t fully know why Faqiri died under the watch of the jail’s staff. An investigation by local police didn’t result in criminal charges, so Yusuf and his family filed a lawsuit in the hope of finding some accountability. In the process, Faqiri’s death has become a catalyst for demanding reforms within Canadian correctional systems for those with mental health issues. “We do not want another tragedy,” Yusuf said at an Ontario Human Rights Commission press conference in 2017. “My brother is gone. He’s not coming back. But there are other people who need to be saved.”

With their home country of Afghanistan enduring a civil war, the Faqiris came to Canada in 1993. The move was abrupt and everything was a blur, especially for the Faqiri children: Yusuf was 9, Soleiman was 7, Sohrab was 2 and Pelatin was just over a month old. The youngest brother, Roustam Ali, is the only sibling born in Canada.

Growing up, Faqiri would defeat his siblings at Donkey Kong, Super Smash Bros. and other video games on their Nintendo N64. He was also physically strong: he played rugby and football in high school and would put Yusuf in headlocks when they messed around at home. But Yusuf says Faqiri wasn’t aggressive. Instead, he was eager to help anyone, from repairing a computer to making someone smile after a long day.

Faqiri was a straight-A student and excited to go to university. In the fall of 2004, he began studying environmental engineering at the University of Waterloo, a southern Ontario school where most first-year engineering students graduated from high school with marks averaging in the 90s. “Everything looked quite linear,” Yusuf says. “It’s like: okay, Soleiman’s got it. And there was no surprise to anybody. Everybody knew that he was going to do some amazing things.”

But that trajectory quickly changed in Faqiri’s second semester when he was in a car accident. Shortly after the accident, doctors diagnosed him with a schizophrenic disorder. Faqiri’s illness meant he could no longer go to school, and so he stayed home, where his mother led the family in supporting Faqiri through his journey with his mental illness.

Yusuf says that in the following years, the core of Faqiri’s personality remained unchanged. A devout Muslim, he used his time to study Islam and even learned how to speak, read and write in Arabic. And he kept his family a high priority — spoiling his nieces and nephews with toys. Yusuf remembers a moment, a few months before his brother’s death, when Soleiman stopped Yusuf on his way out the door on a cold morning to give him his toque and a kiss on his forehead.

Still, Faqiri struggled. According to police documents seen and reported on by the Toronto Star and The Fifth Estate, he was inconsistent with taking his medications, and police apprehended him about 10 times under the Mental Health Act. That act permits officers to apprehend individuals if there are reasonable grounds to believe a person is acting disorderly and is at risk of causing harm to themselves or others. Usually, that person is then taken to a hospital to be examined by a doctor.

More on Broadview: Moms raising their babies in Canadian prisons

In early December 2016, Faqiri was arrested and charged with assault, aggravated assault and uttering threats after an altercation with neighbours in which one of the neighbours was stabbed in the stomach. Faqiri’s family says he was in the midst of a schizophrenic episode. This time, instead of going to the hospital, he stayed overnight in custody at a police station. He appeared in court the next day for a bail hearing, and he was sent to the Central East Correctional Centre, a provincial jail in Lindsay, Ont.

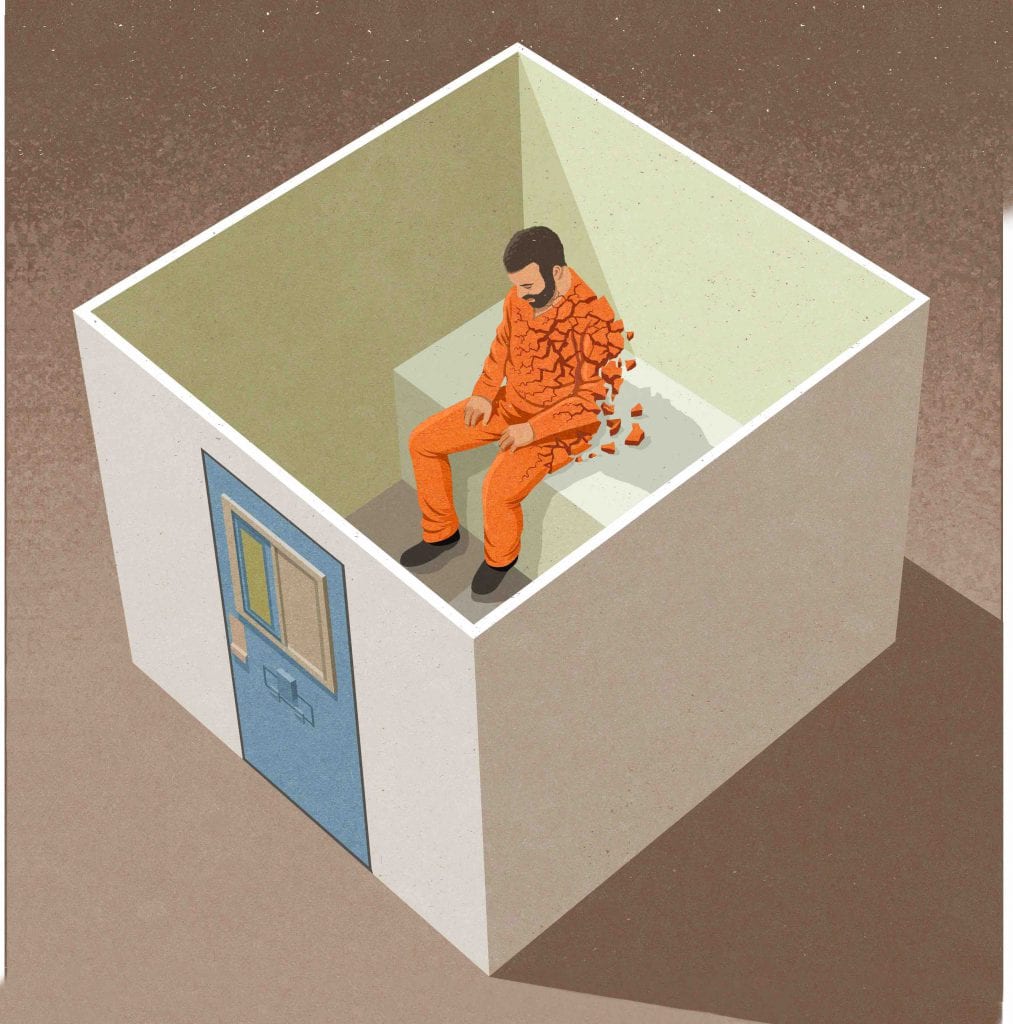

The next day, he was moved to segregation, where inmates are isolated for 22 or more hours a day. The drab segregation cells in Ontario jails are typically small, and some are so cramped it would be difficult for a tall person to comfortably lie down. Outside are concrete yards usually covered by a canopy of either chain link or barbed wire, where inmates have to crane their necks to see a patch of sky.

During Faqiri’s stay at Central East Correctional, his family members were told they couldn’t visit him, despite making the 45-minute drive to the jail four times, but they weren’t told why. The family informed staff that Faqiri had a mental illness and he needed special care.

On Dec. 12, 2016, Faqiri attended a court hearing via video. The judge ordered a mental health assessment to determine if he was fit to stand trial. He was returned to segregation until he could be transported to the hospital.

On Dec. 15, Faqiri was taken to have a shower before being transferred to a new cell, but he refused to leave the showers. What happened next is detailed in the documents seen by Toronto Star and The Fifth Estate reporters. After a mental health worker helped calm him down, Faqiri agreed to be handcuffed as five guards escorted him to his new cell. A sixth guard joined, and Faqiri began resisting. (One eye witness told The Fifth Estate that a guard had whispered something to Faqiri, which is also alleged in the family’s statement of claim for their lawsuit. Ontario’s statement of defence denies this.) Guards pepper–sprayed Faqiri before bringing him inside his segregation cell, which, unlike the hallways, had no video surveillance.

The statement of claim also alleges that guards continued using physical force on Faqiri while he was lying face down on the floor. They put a spit hood over his head and restrained his legs. (Allegations in the statement of claim have not been proven in court.) Ontario’s statement of defence denies this series of events, and says that the only force used was required to transfer a resisting Faqiri to his new cell.

The guards called for any available staff to assist, and according to The Fifth Estate and the Toronto Star, more than a dozen arrived. When they left the cell, staff noticed Faqiri might not be breathing. Someone called 911, but life-saving efforts didn’t work. Faqiri was dead.

Yasin Dwyer is an imam and was a full-time prison chaplain for Correctional Service Canada (CSC) until 2014. He still volunteers as a chaplain for inmates in Ontario federal prisons. Islam, he says, teaches Muslims to think of others as mirrors: what you see in one person is what you could also see in yourself. To him, Faqiri’s death is an egregious reflection of how Canadian society fails to protect vulnerable people with mental illness. “We really should be ashamed of that. However, we need to translate our shame into something proactive to make sure that it never happens again.”

As a full-time chaplain, Dwyer would usually spend half an hour to an hour with each inmate, but was often granted more time if there was a crisis, such as when someone was in distress. Dwyer worked closely with prison psychologists and mental health practitioners and could refer an inmate for therapy. Yet he sometimes feels that chaplaincy is used as an alternative to psychological help. “I think this is one of the tragedies of prisons within Canada: a large number of prisoners do not have their mental health issues addressed in a way that you would expect from a first-world country.”

With budget cuts, there have been steady closures of Canadian mental health facilities over the past several decades. An increasing number of people who might have checked in as patients are ending up behind bars, which some advocates refer to as the “criminalization” of mental illness. Currently, people with mental health issues are statistically over-represented in the prison system. According to Toronto’s Centre for Addiction and Mental Health (CAMH), prisoners are four to seven times more likely to have a mental illness than those in the outside world.

More on Broadview: How one police force approaches mental health

In the federal system, mental health services are provided by CSC, including on-site psychologists, counsellors or social workers. CSC also has some of its own regional treatment centres, but it doesn’t have enough space to accommodate many of the inmates who need ongoing help with mental illness. The Corrections and Conditional Release Act authorizes CSC to also direct inmates to outside psychiatric hospitals, but according to the Canadian Human Rights Commission (CHRC), this doesn’t happen often enough. This insufficient treatment, according to the CHRC, results in inmates being put in situations such as segregation, which could aggravate their symptoms because it removes them from meaningful human contact for days — sometimes months.

In fall 2016, Howard Sapers signed a two-year contract with the province of Ontario to conduct an independent review on segregation and to create recommendations for reforms. Sapers was previously the Correctional Investigator of Canada and an ombudsman for federal prisoners.

What motivated his appointment was the case of Adam Capay, an Indigenous man who spent over 1,600 days in segregation in jails in Thunder Bay and Kenora, Ont. From June 2012 to December 2016, Capay lived in a series of windowless segregation cells. For most of that time, the lights were on 24-7. Sometimes he’d be allowed into the day area or even a yard, but he would still be alone. There was almost never a television or radio. He had access to reading material, but in Thunder Bay, where he spent the majority of these days, he could only have one book or magazine at a time. Without much interaction with others, he eventually lost his ability to speak coherently.

Studies on isolation prove that it can negatively affect anyone’s mental health. In the case of Capay, he cut his forearm and would hit his head against his cell wall. Psychological consequences like these are the reasons why Juan E. Méndez, former United Nations special rapporteur on torture, believes that segregation should be banned in most cases. In 2011, he told a General Assembly committee that “it can amount to torture or cruel, inhuman or degrading treatment or punishment when used as a punishment, during pre-trial detention, indefinitely or for a prolonged period, for persons with mental disabilities or juveniles.”

One of Sapers’ reports found that although Ontario’s overall jail population decreased by 11 percent from 2007 to 2016, the number of inmates placed in segregation rose by 24 percent. And in 2016, people with mental illnesses spent around 30 percent more time in segregation than the rest of the jail population in the province. “There’s really nothing therapeutic or comfortable about these environments,” Sapers says.

His recommendations include prohibiting some people from ever being segregated, such as pregnant women, those with a history of suicide attempts or chronic self-harm, and those with significant mental illness. He’s also pushing for better staff training around mental health.

“My brother needed a bed and a doctor, and instead he got handcuffs and fists.”

Yusuf Faqiri

That would have helped Joseph*, who was a correctional officer in four different Ontario provincial jails over 26 years. Retired since 2015, he says he doesn’t recall receiving any formal mental health training, besides how to spot a potentially suicidal inmate. This left Joseph to devise his own tactics to look out for inmates’ well-being. He would sometimes offer an inmate he thought was anxious a small treat, like cookies or juice. “Just something extra, because everybody feels like they basically had everything taken away,” Joseph says.

According to Brent Ross, a spokesperson for the Ministry of the Solicitor General, all correctional officers have to take a course on managing inmates with mental health concerns during their basic training, which includes more than four hours of theory and scenario-based exercises. He says officers receive related refreshers every two years and that in 2016, 92 percent of officers had one-and-a-half days of additional training in identifying and responding to mental health crises.

Sapers says he sees current curricula more as “mental health awareness as opposed to mental health intervention.” He feels there aren’t enough opportunities for role-playing possible scenarios, and that there’s a lack of good follow-up training on a routine basis. Ross says the mental health training is currently under revision, and correctional officers will go through the revised course in 2020.

In terms of segregation, courts in British Columbia and Ontario have been considering legal challenges to the practice in federal prisons since 2015. In both provinces, judges decided that the segregation process violates the Charter of Rights and Freedoms — decisions that have since been upheld by their appeal courts. The Ontario Court of Appeal also decided to cap the duration of any inmate’s segregation at 15 days.

But in April 2019, the federal government asked the Supreme Court of Canada to allow it to appeal the Ontario court’s 15-day cap, stating that “there is currently no alternative recourse to address these situations.” While it waits for the Supreme Court’s response, the government was granted extensions on fixing the Charter violations. In June 2019, for example, Bill C-83 became law, which replaces segregation with “structured intervention units.” These aren’t to be used for disciplinary purposes and include four hours of time outside the cell. In November 2019, the federal government also asked for leave to appeal the B.C. court’s ruling. At press time, the Supreme Court of Canada hadn’t released a decision on whether it would hear the federal government’s appeals.

For provincial jails, the Human Rights Tribunal of Ontario issued an order in January 2018 requiring the province to stop using segregation for people with mental illnesses “except in the most exceptional circumstances” and to implement new accountability and transparency mechanisms. In May 2018, with the help of Sapers’ reviews and recommendations, Ontario’s then-Liberal government passed legislation that would reform how correctional institutions are run within the province. The new act promised to update rules and definitions surrounding segregation, improve living conditions in jails, and to be more supportive of individual inmates’ rehabilitation and reintegration into society. The current Progressive Conservative government, however, hasn’t proclaimed it into law. “So we’re still oper-ating under the old law, which is a shame really,” Sapers says.

Faqiri’s body now rests in a cemetery in Ajax. His black grave plaque reads: “You are loved beyond words and missed beyond measure.” Yusuf tries his best to visit once a week. When he’s there, he always recites the Fatiha, a prayer that makes up the first chapter of the Qur’an, asking Allah for guidance.

Faqiri’s family still has questions and much anguish. In October 2017, the Kawartha Lakes Police Service finished an investigation into Faqiri’s death, found no grounds for criminal responsibility and didn’t lay charges. According to the family’s statement of claim, three staff members of the jail were dismissed from employment with cause the following year. Ontario’s statement of defence says one of them has since been reinstated. As a result of the initiative of the coroner’s office, the criminal investigation into Faqiri’s death was reopened and is now being conducted by the Ontario Provincial Police.

The Faqiris are currently suing the Ontario government, the superintendent of the jail and 10 individuals for $14.3 million. “My brother needed a bed and a doctor, and instead he got handcuffs and fists,” Yusuf said at the Ontario Human Rights Commission. “My brother should not have died the way he died.”

Ontario’s statement of defence acknowledges that the family has “suffered a tremendous loss in the death of their son and brother,” but denies that Faqiri’s rights were violated or that battery or negligence occurred. In an email, Ministry of the Solicitor General spokesperson Ross says: “Our thoughts are with the family and other loved ones of Mr. Faqiri. As this matter is subject to litigation, multiple investigations and a future coroner’s inquest, it would not be appropriate to comment.”

Yusuf, with the help of family, friends and supporters across the country, also started the Justice for Soli movement, which demands answers to Faqiri’s death, accountability from the jail and justice system reforms to better accommodate people with mental illness. On their logo is an image of Faqiri, his eyes looking up while his lips are arched into a gentle smile. “His life should not be forgotten,” says Yusuf. “Because if we forget his life, then another family that has a loved one with mental illness will suffer as well.”

*Name has been changed

This story first appeared in Broadview‘s January/February 2020 issue with the title “Soli’s story.”

Broadview is an award-winning progressive Christian magazine, featuring stories about spirituality, justice and ethical living. For more of our content, subscribe to the magazine today.

Government have to put more money into mental health. Government have to be better educated around these issues and give it priority when it comes to legislation. These are mentally ill human beings and need to be treated as such, not with extreme cruelty but with compassion empathy and understanding.