The spot where George Floyd was murdered in broad daylight by a Minneapolis police officer is mere kilometres from my home. Suddenly, my state was centre stage in the anti-racism movement, and I had to grapple with my own experiences as a Black, biracial woman and the fears I have for my young children.

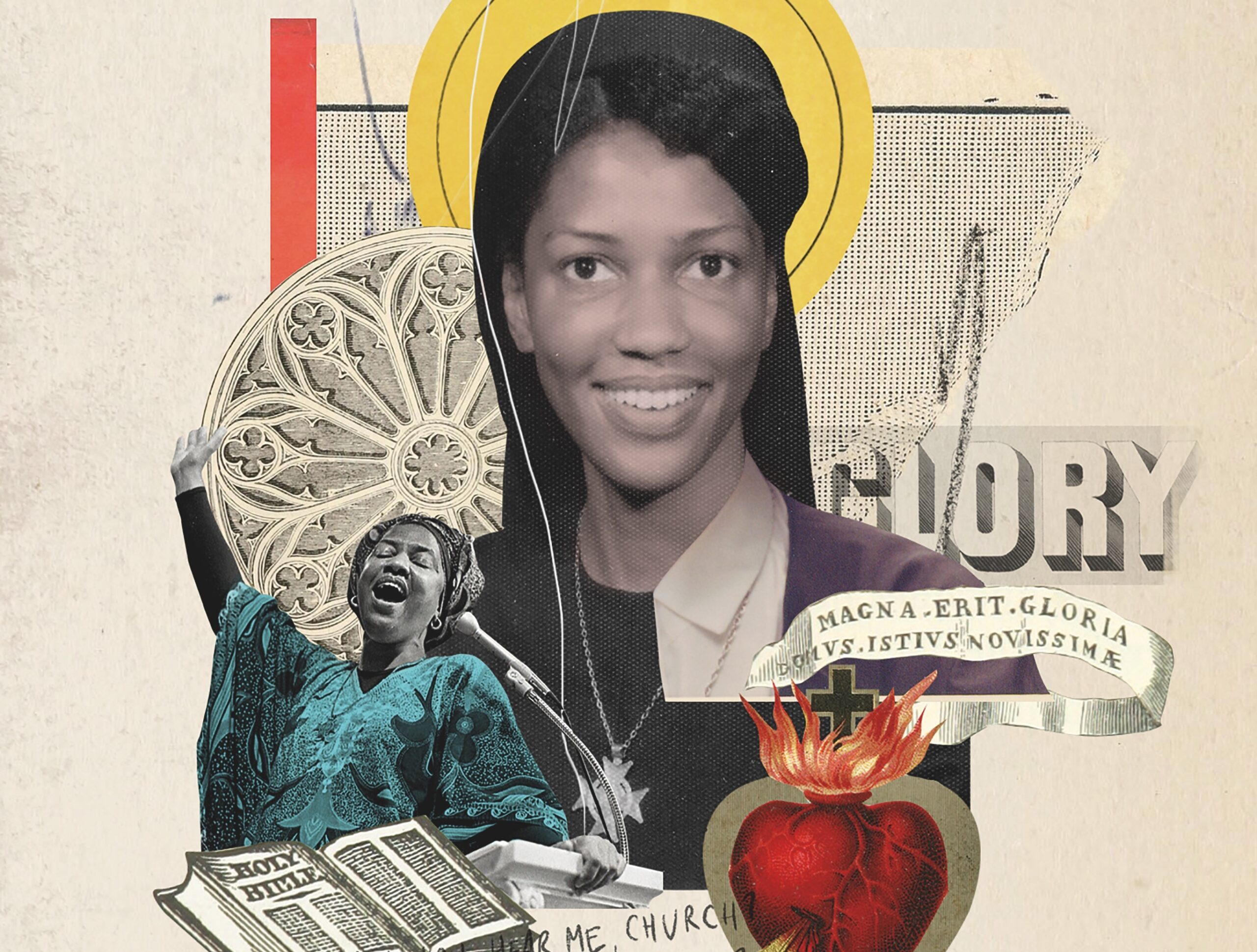

I felt a strong urge to speak up; I just didn’t know how. In difficult situations, I often consult the Communion of Saints for their guidance and intercession. So, at that moment, I turned to Sister Thea Bowman, an American nun who is in the process of being canonized.

You may unsubscribe from any of our newsletters at any time.

With great tenacity, Sister Thea, as she was known, devoted her life to celebrating gifts of Black Catholics and to speaking out against racism in the church. Growing up as a Black child in Mississippi in the 1940s, she understood that education was the key to racial equity both in the church and in society. Her ministry was devoted to sharing the beauty and necessity of Black culture and the Black Catholic experience across the United States and African countries. For all of these reasons, in the days following Floyd’s death, I knew asking for Sister Thea’s intercession would help me find a way to speak out against the sin of racism.

More on Broadview:

- Derek Chauvin’s guilty verdict is a wake-up call for us bystanders

- Dear St. Teresa of Ávila, I love you but some of your ideas are nonsense

Born on Dec. 29, 1937, Bertha Elizabeth Bowman was the granddaughter of an enslaved man and the only child of Dr. Theon and Mary Esther Bowman, who affectionately called her Birdie. The family settled in Canton, Miss., where Theon chose to provide medical care for the underserved Black community. Mary Esther was a teacher who instilled in her daughter a love of singing and education. However, Mississippi’s Jim Crow-era public schools were severely underfunded, and the quality of education was so lacking that the Bowmans eventually enrolled Birdie in a mission school staffed by the Franciscan Sisters of Perpetual Adoration.

Young Bertha was so moved by the sisters’ devotion to social justice that she converted to Catholicism at age nine and joined the convent when she was just 15. Though her parents also eventually became Catholic, they were at first adamantly against this. In time, they let her go, and Bertha was the only Black person in the entire order when she arrived in 1953. She faced racism in the convent. In his biography Thea Bowman: Faithful and Free, Rev. Maurice Nutt writes that she “entertained insulting questions about her hair texture, skin color, and the entire black race.” Like other Black people who enter religious life or the priesthood, Bertha learned to quickly assimilate to survive her time in the convent.

In 1956, she was given the religious name Sister Mary Thea and professed her permanent vows in 1963. She completed her bachelor’s degree and went on to earn a master’s and doctorate in English literature. She had a prolific teaching career. Sister Thea was a founding faculty member of Xavier University’s Institute for Black Catholic Studies and helped establish the National Black Sister Conference, an organization devoted to supporting Black religious sisters and challenging racism in the church.

Two of Sister Thea’s greatest gifts were her singing and preaching. She captivated audiences around the world with a message of encouragement, hope, resistance and transformation. She called on white communities to make space for people of colour in the church and to embrace diversity. Racism goes against the Gospel, as it thrives on marginalization and dehumanization. Sister Thea showed that resistance against racism compels us to live the Gospel more fully and to create a more loving and just society for all.

More on Broadview:

- There’s still room in my heart for St. Francis, even centuries after his death

- How I learned to embrace St. Anne like my high-waisted mom jeans

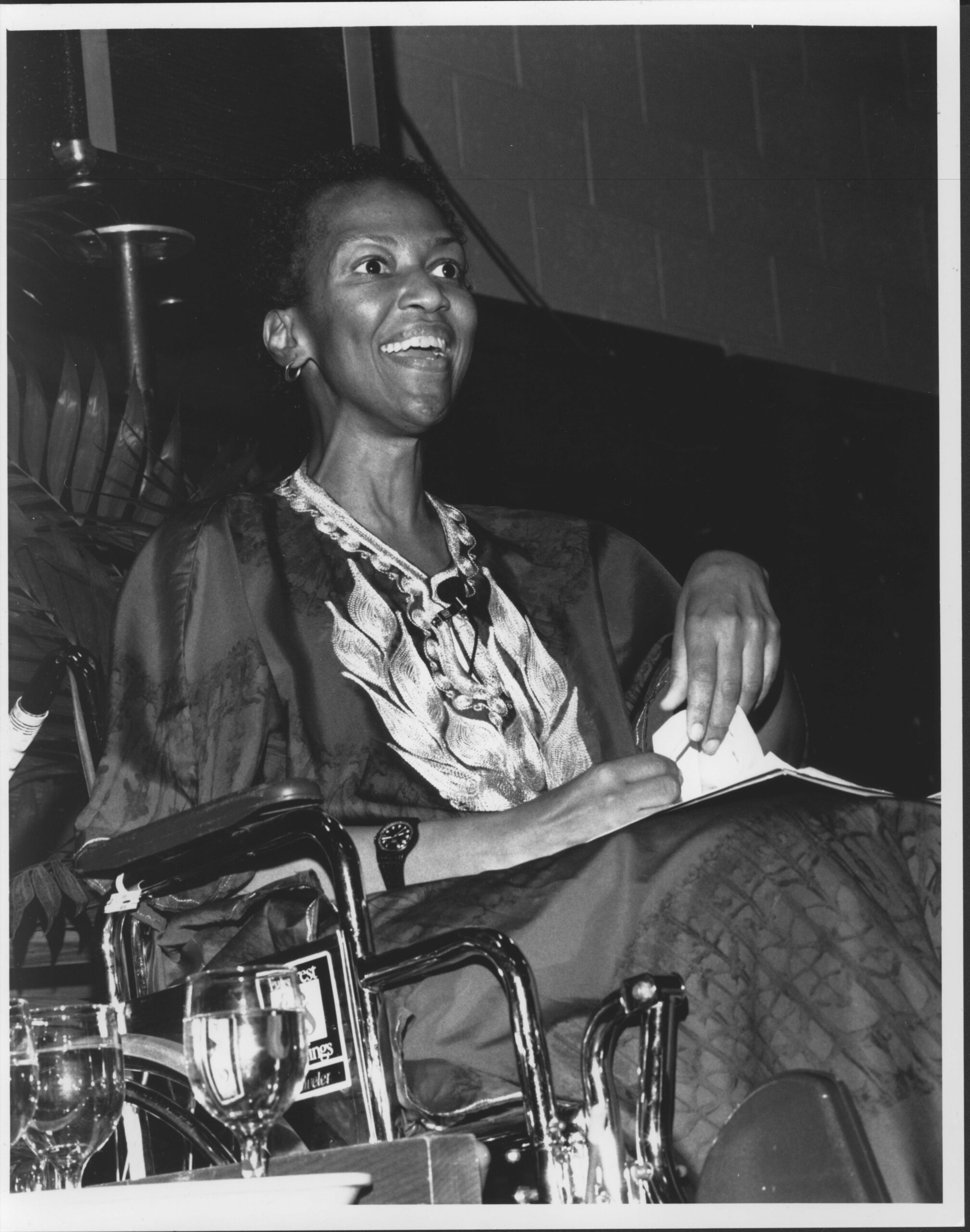

Just months before her death from breast cancer at age 52, Sister Thea spoke at the 1989 United States Catholic Conference of Bishops. Addressing their annual meeting, she posited:

“What does it mean to be Black and Catholic? It means that I come to my church fully functioning. That doesn’t frighten you, does it?

“I come to my church fully functioning. I bring myself; my Black self, all that I am, all that I have, all that I hope to become.

“I bring my whole history, my traditions, my experience, my culture, my African-American song and dance and gesture and movement and teaching and preaching and healing and responsibility as gifts to the church.”

When I read this speech years later, Sister Thea spoke right to my heart. She was joyfully and wholly a Black Catholic woman — and she knew this was a gift to the church. Sister Thea had survived the Jim Crow South and participated in the civil rights movement. To resist the hatred and to refuse to view her Blackness as a weakness meant radical transformation.

Sister Thea daringly asked the bishops “That doesn’t frighten you, does it?” What if I could be as bold as Sister Thea and take up my rightful space in the church and in society? Sister Thea knew her Blackness was truly not a threat to the Gospel. Neither is mine. As I watched other Catholics on social media and in my community find ways to scrutinize George Floyd’s character or justify not taking an anti-racist stance, I realized that my voice could also be a gift to the church.

So I started sharing my story and speaking out against racism on social media and with my white family members and friends. As I spoke, I felt within me the boldness that comes with truth.

I pleaded with my fellow Catholics and other Christians to root out the sin of racism in their hearts and spheres of influence, no matter how small. I participated in a women’s Share the Mic movement in which Black and other people of colour took over the Instagram accounts of white women to share their experiences with racism and call their followers to action.

Speaking out cost me some friendships and relationships, but it was empowering to call Christians on to a greater love.

The catechism of the Catholic Church explains that racism is to be curbed and eradicated, so we have a duty to speak up. Sister Thea saying “Can you hear me, church? Will you help me, church?” is really a call to action — not just to those bishops in 1989, but to each of us. May we be so bold as to answer the call to make space for all of our brothers and sisters, and embrace the beautiful, necessary diversity of our church.

***

Justina Hausmann Kopp is a writer and mother of quadruplets based in Twin Cities, Minn.

This story first appeared in the July/August 2021 issue of Broadview with the title “The gifts of Sister Thea.”