The day after my husband retired, he disappeared into the garage with a set of plans and a toolbox. A year later, he emerged with a beautiful handcrafted cedarstrip canoe.

You could call him a template for what to do right about retirement. He had a project he could hardly wait to start. He had two lifelong passions — amateur radio and flying — that had been starved for time while he was working. He kept up with friends who shared his interests.

You may unsubscribe from any of our newsletters at any time.

Then there’s my brother, the how-not-to-retire man. He has worked for one company all his life. Outside the office, he has no interests and no social life. His work is what he lives for. “If I retired,” he asks, “what would I do? I’d be dead.”

He is in a minority, fortunately. Most people transition smoothly from nine-to-five to every-day-is-Saturday. At first, they may feel lost without a structure to their days, neglected without urgent phone calls and emails, or lonely without the companionship of colleagues. Or oppressed with Presbyterian guilt to be reading the paper over a second cup of coffee while everyone else is working. Most get over it. But some don’t — as many as 30 percent in one survey. They report feeling bored, useless, depressed, even suicidal. Right now, some seven million Canadian baby boomers are heading into their 60s and nearing retirement. They would be well-advised to pay close attention to their elders who are already there and know a thing or two about what to expect in retirement and how to (or how not to) handle it. Because sooner or later, it happens to everyone. Unless you die first.

Which our grandparents often did. Eighty-five years ago, a man could expect to live to 59, a woman to 61. Now it’s 76 for men and 82 for women. Meanwhile, the median age for retirement is going down to the early 60s. That means we can expect to live another 20 years, a quarter of our lives, mostly in good health, with time on our hands.

There’s a stereotype of the retired: lonely, useless old fogeys, past their best-before date, stuck in a rocking chair watching television and waiting for the mail. That might have been true of Grandpa. It’s not true today. Neither will we all be frolicking on a Florida beach, thanks to this or that patent medicine or insurance product. If we have prepared properly — and according to Statistics Canada, 29 percent of us don’t prepare at all — we’ll be like Don Clysdale of Callendar, Ont., who quips, “Sometimes I say I should get a full-time job so I can have some spare time.”

One of the first steps to a satisfying retirement like his is recognizing that you’re not at the end of the line; you have just changed trains. You’ve lost the reason you used to get up in the morning. On the other hand, your time is all your own, perhaps for the first time in decades, and you get to define what to do with it.

Very Rev. Marion Pardy, of St. John’s, Nfld., had a “sense of loss” on retiring both as moderator and as a pastoral minister “but a greater sense it was the right time. When I work, it engages most of my life. It was time to let go of that kind of intensity.”The second step is one you take long before you retire. Get a life. Start now to develop those interests that will give you reasons to get out of bed. “Who you are in your middle years is a fair index of who you’re going to be in later years,” says Gregory Bassett, executive director of the Brant Interfaith Counselling Service in Brantford, Ont. What are the patterns of your life? he asks. If you have a sense of service, of outreach to others, you don’t change as you age. He made me think of Catherine Scroggie, a Toronto friend, who at 93 was still making weekly visits and baking cookies for the “old folk” at a veterans’ hospital.

You have to build on that pattern over the years. “The day after you turn 65 is too late to start,” says Rev. Donald Gillies of Burlington, Ont. If you have spent all your working life in one place and have no interests outside your job, no friendships away from work, no social supports, you’re going to have a problem. You’ve identified yourself with your work, “and why wouldn’t you, when you’ve spent so many hours devoted to it?” asks a provincial deputy minister quoted in a survey developed for the Canadian Centre for Management Development (CCMD).

“If you don’t have interests outside your work, you’re in trouble,” agrees Owen Ricker, a retired University of Regina professor. “We’ve known some who were lost without their work. They didn’t live very long.” (One hears this a lot, although there’s no conclusive research that it is true.)

We all identify ourselves to some extent by our work. I’m a teacher, we tell others, or a rancher, or a bus driver. And it’s legitimate in terms of our biblical heritage to identify ourselves in terms of the gifts we have been given, says Rev. James Christie, dean of theology at the University of Winnipeg. The problem comes when you identify yourself exclusively in terms of your work, and even more by your status. It’s the gifts that define us, not the position, and the challenge is to continue to employ them when the position is no longer ours. “Do we take these gifts and bury them in the backyard when we retire?” he asks, recalling the parable of the talents.

Many of us, like Ricker himself, have lifelong talents that multiply in the freedom of retirement. Ricker had been singing in choirs all his life. In retirement, he took singing lessons, joined a musical theatre company and has appeared in half a dozen Broadway-type shows — the first, Fiddler on the Roof, in which he played the rabbi. Pardy has time now for aspects of ministry that always drew her, such as interchurch, interfaith and social justice work.

After Clysdale retired as an engineer at Nortel, he took a year-long chef’s course (“I’d always done some of the cooking, the high glory items”); having played the viola since Grade 9, he joined the North Bay Symphony as principal viola and vice president; and after taking a lay preaching course is preaching monthly until June. Gillies has revived committees, chaired boards and on the day we talked was practising to play the piano with Symphony Hamilton. “My identity is in making a contribution to what is happening in the world,” he says.

Ruth Evans of Toronto, laid off from the national United Church office, found “lots of identities to fall back on,” as women often do: mother, grandmother, gardener, volunteer. “I need to belong somewhere where there is meaningful movement to change the world. The time to do something about it is one of the pleasures of retirement.” Many other seniors — 800,000 last year — are volunteers like Evans, and non-profit agencies would shrivel without them. The economic value of their time has been estimated at up to $2 billion.

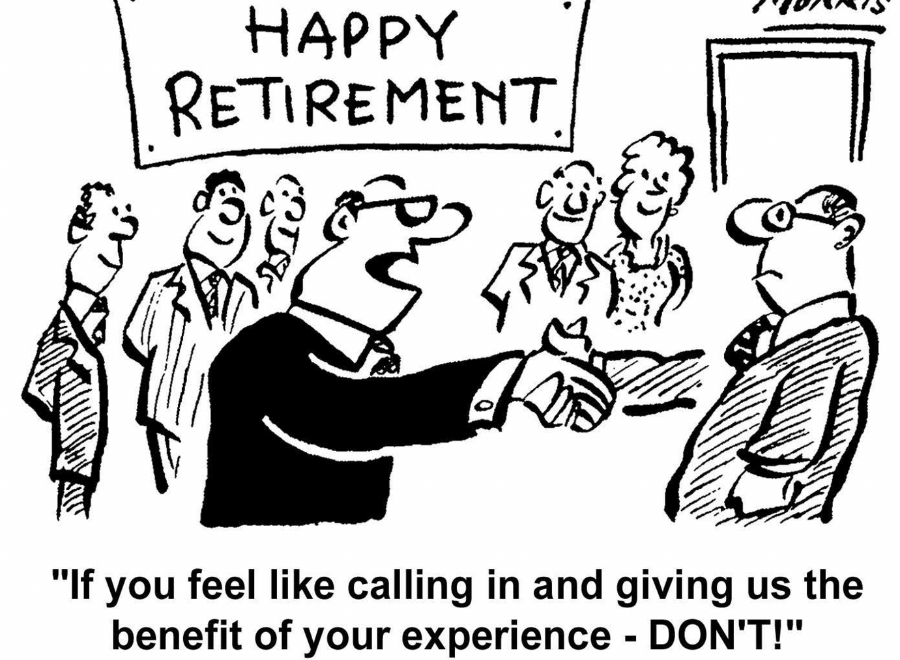

Gifts of time, talent and experience are on offer, but the gifts aren’t always welcome. Sometimes the loss of identity is more an issue for others than for the person who is retired, Marion Pardy says. “We still are who we are and could be a valuable resource, but others may see us as a threat. We are happy to have someone else assume responsibility, but we want and need to share our gifts.” A retired minister in a small and isolated western community is feeling that his gifts are no longer appreciated. “It’s hard to let go when you’ve worked hard all your life and then somebody does things differently,” he says.

So you’ve been investing in your future, nurturing your gifts and passions and planning financially, although that’s another story. You don’t have to jump right in to a new identity on the first day of your new journey. Give yourself a break. Take what a friend calls “soul time.”

“You leave the old identity behind. It takes time before you describe yourself in terms of your new identity,” the CCMD project quotes a former national director general who admits his first year was “very difficult.” Most women have domestic routines to fall back on. Even while employed, Statistics Canada reports, the average woman spends almost five hours a day on unpaid work. They are used to a slew of identities: mother, homemaker, best roses on the block, best cook in the UCW. Men, more often, hit the wall.

A civil servant in the CCMD study reached back to her Prairie roots to suggest a need to “lie fallow” to renew oneself. Pardy retreated for a month to relax at her cottage. When I retired as interim editor of The Observer, the first thing my husband and I did was soak up the blossoming spring gardens of the American south. I didn’t know it, but that’s the kind of spirit-renewing break that retirement coaches suggest.

Since no money-making opportunity goes unexploited, retirement planning for baby boomers is a growth industry. Examples: a Boomertirement Conference in New York last year; serious studies by think tanks on how the relatively few post-boomers can pay for pensions for the many more and long-lived boomers; a novel by Christopher Buckley, Boomsday, in which a Generation Xer solves that problem — tax incentives to encourage boomer suicides; manufacturers designing tools, clothes and cars to appeal to boomers’ aging bodies and fat wallets; and a proliferation of retirement coaches offering “a purpose-filled and passionate Third Age.” But I digress.

Sometimes it helps to have a ceremony symbolizing letting go of the old identity. For Pardy, presiding over the election of her successor and then passing on the stole of office “enabled me to move on.”

On the other hand, Allan Petrie of Mississauga, Ont., a former bank executive, had no trouble letting go of work. “The truth is I forgot about it almost instantly. I didn’t think it would be so quick.” Instead, he ran into another and not uncommon problem.

“The best advice I got about retirement was from a bank colleague. He said to prepare for a change in your relationship with your wife. It will be more difficult than you expect. And he was right. The adjustment was not easy.” His wife, Paula, agrees. “I absolutely had to change my life.”

There is an old saying, “I married you for better or for worse but not for lunch.” A newly retired husband gets in a stay-at-home wife’s hair, upsets her domestic routine, hogs the telephone or the television or the family car. His world has shrunk; hers has suddenly become crowded. They both need space.There are more stay-at-home wives in my generation than there are among the baby boomers. Theirs is the first generation of women to be in the labour market most of their adult lives, and adjustment to retirement may be different for them. Gregory Bassett points out that both partners may be highly competitive, coming from a place of control and having had little time for outside activities. What worked in a busy marriage for years doesn’t work when you’re sitting home staring at each other. You need to renegotiate the relationship.

That’s not all that may need to be renegotiated when seven million of us, mostly healthy, are living on pensions and savings. Retirement is a fairly recent phenomenon. It made sense when workers (nearly all of them male) were worn out at 65 and younger people needed their jobs. It makes less sense when in 10 years, there will be more Canadians at an age to retire than at an age to start work. That will force us to rethink our pension and retirement policies. In the United States, social security administrators are bracing for what they call the “silver tsunami.” The first waves already are upon us.

Some boomers will retire then continue to work part time, by choice or by necessity. Almost 20 percent of us have told Statistics Canada we don’t plan to retire at all. And that’s okay. Biblically, one’s call is to use one’s gifts, whatever they may be, in the best way as long as one is able.

Take Sylvia Hamilton, a commissioned minister in Toronto who is 79. She has retired four times and is back in ministry again. It’s not for the money. She loves her work. “I was a late bloomer in coming to ministry. That makes the time more precious,” she says. “I need to be active, stirring up things, asking uncomfortable questions. Otherwise, I’d sink into apathy.”

Maybe I should stop nagging my brother to retire.

After all, he’s happy. He’s using his gifts. He hasn’t prepared any alternate way of using them. Reg Lang, a retired York University professor, told a York faculty retirement seminar about Leonardo da Vinci, who on his deathbed was still at work, recording in his notebook the scientific details and symptoms of his illness. Perhaps that is my brother’s calling, too.

Remember the story of Elijah? He went into the wilderness, hid in a cave and wanted to die. But God came after him, called him out and told him to get moving. In Christie’s words, God’s message was, “I’ll tell you when you’re going to retire.”

***

This story first appeared in The United Church Observer’s March 2008 issue with the title “When your time is your own.”