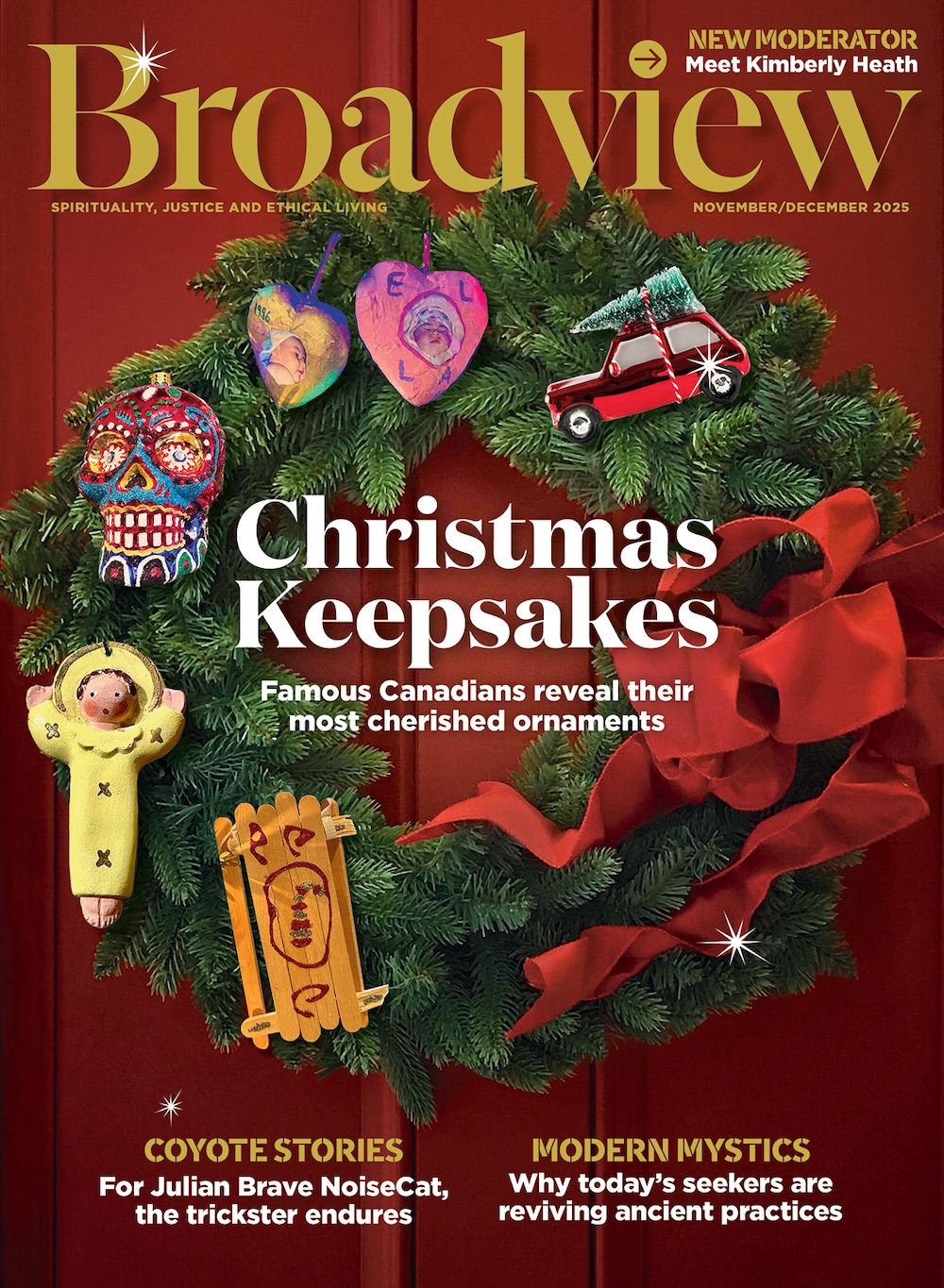

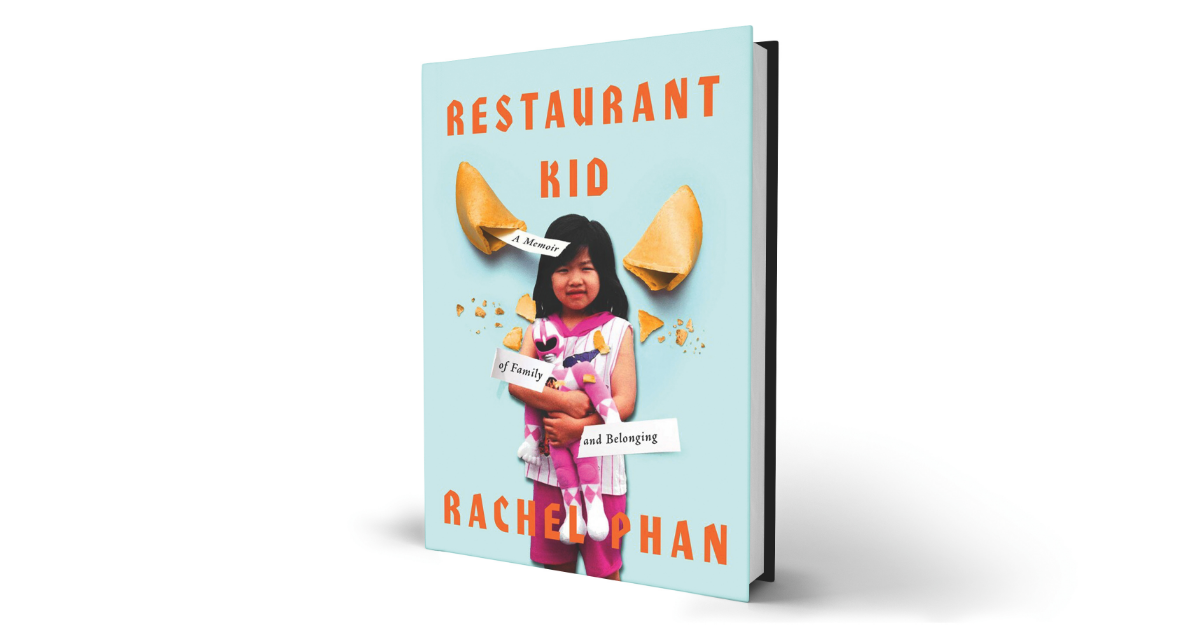

Restaurant Kid is Rachel Phan’s first book. The memoir traces her experience of growing up in the 1990s and early 2000s under the shadow of her parents’ business, a restaurant in Kingsville, Ont., serving Chinese Canadian cuisine. It’s a tale of navigating life as a first-generation immigrant in a town where few people looked like her and her family struggled to understand her. In conversation with Abhisha Nanda in Toronto, Phan speaks to how writing the book has transformed her relationship with her parents.

ABHISHA NANDA: What inspired you to write a memoir?

You may unsubscribe from any of our newsletters at any time.

RACHEL PHAN: Growing up, I never saw families like mine represented, so I thought, if that representation isn’t out there, maybe I should create it. I wrote an essay for CBC about being a restaurant kid, which got some amazing feedback and led to meeting my agent. Since the book came out, I’ve had a lot of people reach out to say, “This is my story too.”

AN: You’ve said you were one of only two racialized people at your school. How has being a minority shaped your experience of Canada?

RP: I grew up in an environment where no one else looked like me. You stick out like a sore thumb, when you want nothing more than to fit in. I tried to change myself to match what was trendy or accepted. Now that I live in a city, I can just be myself. I’m grateful to live in a diverse place like Toronto.

AN: “Restaurant kid” seems to represent more than just the title of your book. Can you elaborate on how a family business can occupy such a large part of one’s identity?

RP: I’ve described the restaurant as my annoying younger sibling — always taking attention, always being the focus of my parents’ time. My parents worked 12-plus-hour days, my older siblings were working there, and I was expected to help out. It was the backbone of our lives. We even lived in an apartment above the restaurant, so there was no escape from it. It was our livelihood, our home, our world, our playground.

AN: You’re candid in the book about your parents’ struggles, including the blow-ups they would have in the restaurant kitchen. How did you navigate being honest in your memoir with protecting your family’s privacy?

RP: I had to find a balance between being honest, but also being fair, loving and compassionate to my family. It was important to me that I show grace to them and my past self as well, because our actions don’t exist in a vacuum — they were direct responses to our environment. We do what we have to do to survive and just blend in.

AN: You write about struggling with depression. How did your diagnosis affect your family dynamics?

RP: My family, like many other Chinese families, just doesn’t talk about mental health. A Chinese psychiatrist once told me, “We have such rich languages, but we have no words for feelings. For a medical condition to be considered real, it has to manifest physically.”

As a teenager, no one understands you anyways, but it’s especially exacerbated when you’ve got a cultural difference. When I ended up being hospitalized for depression in my later teens, it marked a turning point in my relationship with my parents. Even though they didn’t understand depression at all, they surprised me by showing up for me.

Growing up, we didn’t take vacations. My parents never took days off. When I was at the hospital, 45 minutes away from where they live, every day without fail, my parents were at the hospital for visiting hours, even though that overlapped with the busy dinner rush. That was the first time I realized maybe I don’t come second place to the restaurant.

More on Broadview:

- Meet the changemaker empowering B.C.’s international students

- From Nigerian refugee to Montreal community leader

- New United Church exhibit showcases Black resilience

AN: What was your family’s reaction to the book?

RP: They were so proud and overjoyed. When I was growing up, my parents were very distant and not vocal about their love — it was all expressed through actions. But after the book, they started saying things like, “I’m proud of you” and “I love you.”

It’s such a gift. Because I wrote this book, we were able to bring things to light and hash things out as a family that we probably would have just kept buried forever. It’s been very healing for us.

This interview has been edited for length and clarity.

***

This article first appeared in Broadview’s September/October 2025 issue with the title “Family Business.”

Abhisha Nanda is an intern at Broadview.