CW: This story contains references to experiences at residential schools. Take care when reading.

Editor’s note: Brown Tom’s Schooldays was originally self-published in 1985 and republished in September 2024 by University of Manitoba Press.

You may unsubscribe from any of our newsletters at any time.

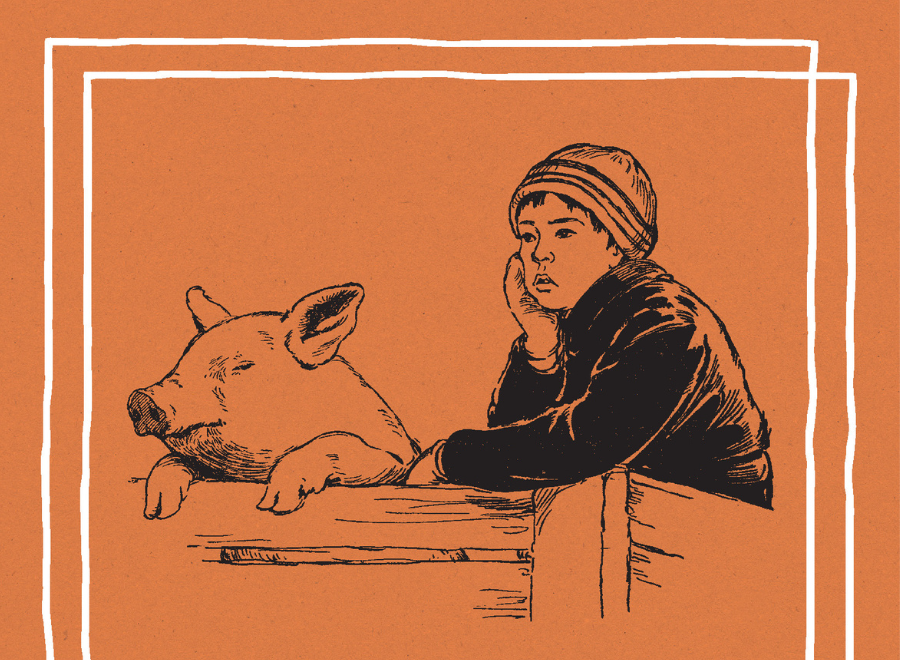

Copies of Brown Tom’s Schooldays emerged into the world on 8.5 x11-inch paper from a Xerox copier machine at M and T Printing, a copy shop in Waterloo, Ontario, in May 1985. It was only six months after its author, Enos T. Montour, had passed away at his seniors’ residence in Beamsville, Ontario, at the age of eighty-five. The book had a brown cardstock cover featuring an image of a boy and a pig leaning on a fence, photocopied from a United Church magazine.

Montour’s fifteen chapters, each approximately 1,600 words long, trace the life of the main character, an “Ontario Indian boy” named Tom, during his time at Mount Elgin Residential School, near London, Ontario. These chapters and editor Elizabeth Graham’s Preface were held together with black plastic spiral binding. One could be forgiven for mistaking Brown Tom’s Schooldays for an everyday 1980s university assignment, rather than a skilful and extraordinary literary text of the school story genre and a rare chronicle of Methodist (subsequently United Church) federal Indian schooling in the early twentieth century.

The only copy I could locate was at the (non-lending) National Library in Ottawa. Historian and archivist Anne Lindsay put me in touch with a researcher who had a digital scan of the book that he shared with me. Even though it was a copy of a copy of a copy of a copy of the original, every grey pixel was like gold to me, because Brown Tom’s Schooldays is set at Mount Elgin when my great-grandfather and his brother attended the school. Mount Elgin student records covering the early twentieth century are extremely thin, and so it is difficult to know their precise dates of attendance, but it is likely that my relatives and Enos crossed paths at Mount Elgin. I immediately wanted everyone to read it! Indigenous accounts of Mount Elgin and Residential Schools generally in years before living memory are very rare, and Brown Tom richly describes times, people, and events. The insights of this generation of First Nations people are vitally important to understanding how twentieth-century Indigenous intellectual history flourished in a context of violent settler racism and colonialism that appropriated not only land and resources but also time, language, headspace, and opportunity.

Thirty years after Brown Tom was put into print, it is cited in the Final Report of the Truth and Reconciliation Commission (TRC) for its descriptions of perpetual hunger and a student’s death from tuberculosis, its explanation of the day-to-day discouragement of Indian languages at Mount Elgin, and its discussion of the impact of the First World War on race relations in Residential Schools. The TRC report also points to the “devastating end” of Brown Tom, when teachers question the usefulness of the school itself: “Had this all been a mistake? Had these gifts not only served to unfit them for the old Reserve life without being able to promise them very much out in the great big Anglo-Saxon world? Had it been for better or worse?” That Montour uses Brown Tom to express his impression of teachers’ self-doubts is a brilliant literary device that highlights the frail but violent core of the Indian Residential School system and the broader Canadian society it reflected.

Excerpt from Chapter Fifteen

Brown Tom “Arrives”

By Enos T. Montour

One Sunday afternoon, during Visiting Hours, the Senior Class was assembled on the lawn. The wide-spreading maples afforded a good shade and the well-kept lawns a good cushion. They were indeed a motley crowd of boys and girls, coming from many different Reserves. Here were Angus Shewung, Mitchell Noash, Alvira Half-Moon, Bessie Ashleaf, Adam Gibson, Lottie Laframe, Welby Roundsky, and Brown Tom.

…

“Lay off my foot, you big walrus,” said Adam to Welby. “You must weigh at least a ton.”

“Look here, fellows,” said Mitchell, “we must be serious. This may be the last chance we’ll have to be together and there’s a lot to discuss. Our people are in bondage to the White man, and their Rights are denied them. We who have some education ought to help them. They ought to get back the land, money and rights that have been stolen from them. Why, I know a reserve . . . .”

More on Broadview:

-

Truth and Reconciliation commissioner’s new book honours residential school survivors

-

Indigenous artist’s mural designs in Port Alberni church represent hope and healing

- Truth before reconciliation

Angus let out a groan and cried, “He’s at it again. Stop him somebody before I see Red and grab a tomahawk or something.”

…

“Seriously tho’,” said Alvira. “What’re you big clumsy boys going to make of yourselves when you get back to the Reserve? Now, me, I’d like to be a nurse. I’d go on the Reserve and heal and soothe all their little hurts. It bothers me to see those little gaffers come to the matron with their scratches to be healed and their slivers to be pulled. They come in here with their long black hair hanging into their eyes and with scars on their ears and faces. Oh there’s so much good to be done.”

“You can start nursing me,” said Adam. “I got me a pain right here in my tummy.”

“Cheer up Adam,” said Alvira. “Supper will cure your pain and when you get home you can have all the gundgeon bread you want.”

Mitchell, the stern Nationalist, could keep quiet no longer: “What’s the use of all this if the Indians are themselves to be treated like dumb driven cattle? I know a Reserve where, by a Treaty, they were promised all the land along a river from its source to its mouth. Today they are huddled in a mere fraction of that.”

“Well Mitchell,” said Adam. “You go hunt up the treaties. I am gonna be busy makin’ a livin’.”

…

Welby hit Angus a resounding whack and said, “Wake up Mohawk, what’s your great ambition in life?”

Angus roared in mock agony and, rolling on his back with his hat on his eyes, said: “My one great ambition in life, when I get out of this Mush ’n’ Milk Jail, is to get me one good square meal.”

The group rocked with laughter, amid cries of “Attaboy, Angus.”

The girls looked at one another and said, “What an ambition.”

Angus sat up saying, “No, I really mean it. I want a real he-man meal of gundgeon bread, potatoes boiled with their skins on, some real fat pork and Thick Man’s gravy.”

“You mean ‘Poor Man’s Gravy,’” said Alvira, “made with flour and browned over a hot fire. Better stop, Angus, you’re makin’ Tom Hungry.”

“Makin’,” said Brown Tom. “Say, I’ve been hungry for four years. But listen you high aimers. Let me tell you my ambition. I am staying with the books. Books have made me what I am.”

…

The day of Graduation finally arrived… These graduates had only been brought to the parting of the ways. The school could lead them no further, nor advise them which road to take. The one road was an unpromising but familiar and well-worn one. It led back to the Reserve life. The other was a bright upland way, but beset by many uncertainties. It led out to the great Anglo-Saxon world of competition and continuous struggle.

There were two lions at the gateway of this latter road. The one was subjective, the other objective. They were an inferiority complex on the one hand, and real narrow race-prejudice on the other.

One wonders what were the private thoughts and emotions of the Staff on that day. Were they satisfied with their work, or did doubts assail them?

…

The doubts that might have assailed them would be these: they had trained these youngsters in the White man’s ways, given them White man’s education. Had this all been a mistake? Had these gifts not only served to unfit them for the old Reserve life without being able to promise them very much out in the great big Anglo-Saxon world? Had it been for better or worse?

***

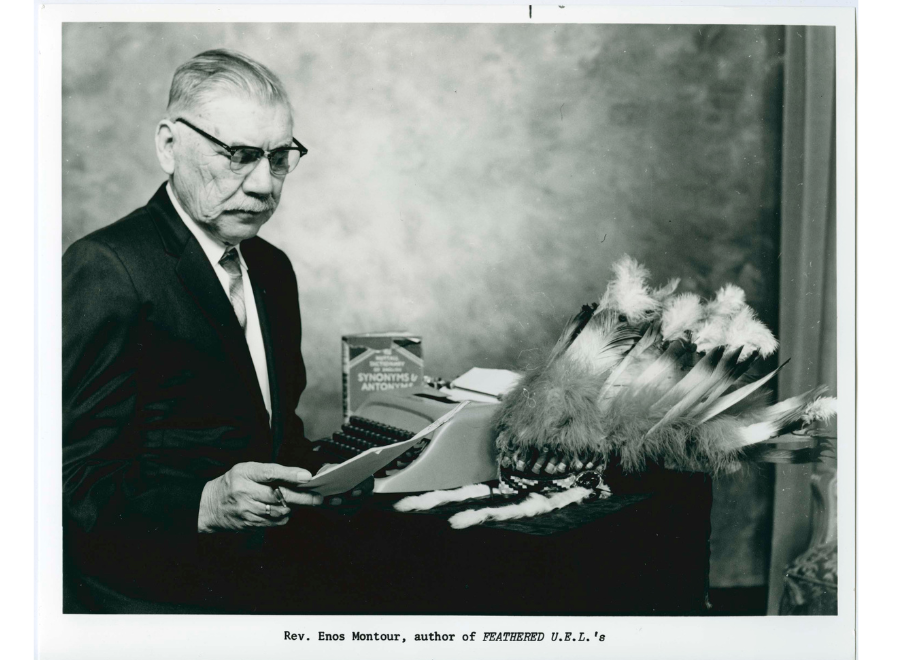

Enos Montour was an United Church minister and writer of Delaware descent who wrote Brown Tom’s Schooldays about his experience at Mount Elgin Residential School from 1910-1915.

Mary Jane Logan McCallum is an award-winning historian and an Indigenous studies expert. Her great-grandfather attended Mount Elgin Residential School, the same school as Enos Montour.