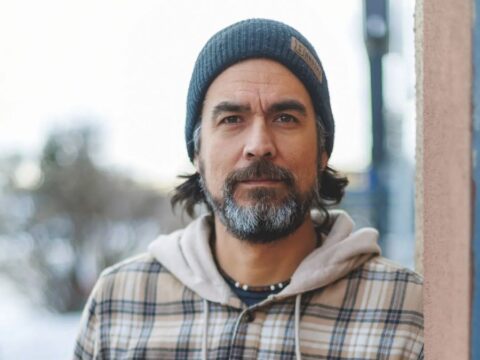

Randy Boyagoda has a problem with heaven. Simply, “Heaven is not funny.”

This wouldn’t matter if he weren’t trying to write the last volume of a trilogy, loosely based on Dante’s Divine Comedy, the three-part medieval epic tracing the Italian poet’s journey through Inferno, Purgatorio and Paradiso. Hell and purgatory, the inspiration for Boyagoda’s first two books in the trilogy, gave the Toronto author plenty of opportunities for humour. “Comedy comes from the drama of human life, of things not working out the way you thought they would,” he says. And to say that hell and purgatory are two places where things haven’t worked out is perhaps an understatement. But the problem with heaven? “It worked out,” says Boyagoda.

You may unsubscribe from any of our newsletters at any time.

Boyagoda is a dab hand at satire and skewering our contemporary pretensions. But he is more than just a comic writer. A very rare bird these days, Boyagoda is also a religious novelist — not simply one who believes or attends church, but one who takes religion as the central focus of his writing. Sixty or more years ago, any well-read person could rattle off a number of such writers: G.K. Chesterton, Flannery O’Connor, Evelyn Waugh, Graham Greene and Walker Percy for the Catholics; C.S. Lewis for the Anglicans. But nowadays, about the only writers who seem to be tagged this way are Donna Tartt and Marilynne Robinson. A serious religious novel (as opposed to, say, an Amish-themed romance) feels like an artifact.

This void is something Boyagoda, also an English professor at the University of Toronto’s St. Michael’s College, wants to fill. “If we only read dead writers, what does it do? It confirms for the publishing industry that, yes, religious fiction matters, but it matters in a way that is historically closed off from the here and now,” he says.

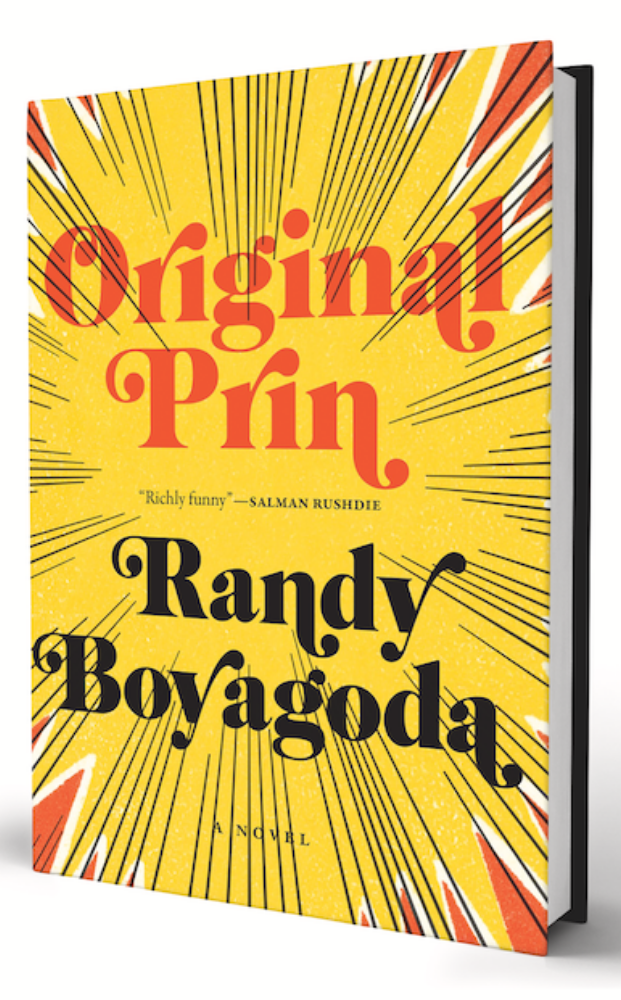

Boyagoda’s books are very much concerned with the here and now. Original Prin, the first novel of the trilogy, traces the story of its title character, a Sri Lankan Canadian English professor whose specialty is the role of marine life in Canadian literature. A married father of four, just recovered from surgery for prostate cancer, Prin finds himself dispatched to the Middle Eastern country of Dragomans (a sort of cross between Syria and Iraq) in an attempt to rescue his university from bankruptcy by forming a partnership for distance education. Along the way, he has to deal with the reappearance of an ex-girlfriend turned academic consultant, not one but two terrorist attacks and a visit to a bizarre shrine where monks pursue a centuries-long dispute over who has the right to show tourists the impression of a saint’s rear end.

That’s an odd example, but Christian, specifically Catholic, themes are scattered throughout the book. Prin’s family goes to church, he attends confession, people pray.

But Christianity is more than window dressing; it underlies the story, animates it. Early in Original Prin, our hero is reluctant to go to Dragomans, particularly as it involves that ex-girlfriend and an unhappy wife, when something happens:

Then he heard it. A voice. The voice.

Go.

Go?

Go.

That moment kicks off a chain of events that will propel the hero through the first and second volumes of the trilogy, and although it’s too soon to say, one assumes the third as well.

Getting that religious depth wasn’t effortless. Boyagoda worked with author and fiction editor John Metcalf during the editing process for Original Prin. He says Metcalf told him, “Randy, the problem with your book is it’s not theologically serious enough. It’s all smells and bells and opinions about Pope Francis. No matter what the reader believes, the reader needs to believe that Prin believes in God.” Boyagoda took the advice to heart, though his books aren’t dogmatic or even all that religiously certain. Prin himself is deeply skeptical of his divine call: “Had he really heard a voice? Really?”

“The lived experience of a believer isn’t totally straightforward,” Boyagoda says. Non-believers often think that the religious have it somehow easier. Not so. “It makes life so much harder if you believe in God and live in a world like ours. Having to account for so much suffering and injustice as a believer is a lot harder if you believe in a benevolent, merciful Creator. So I think what I’m trying to do is just convey that messiness, the messiness of a life lived in faith and also lived in the world.”

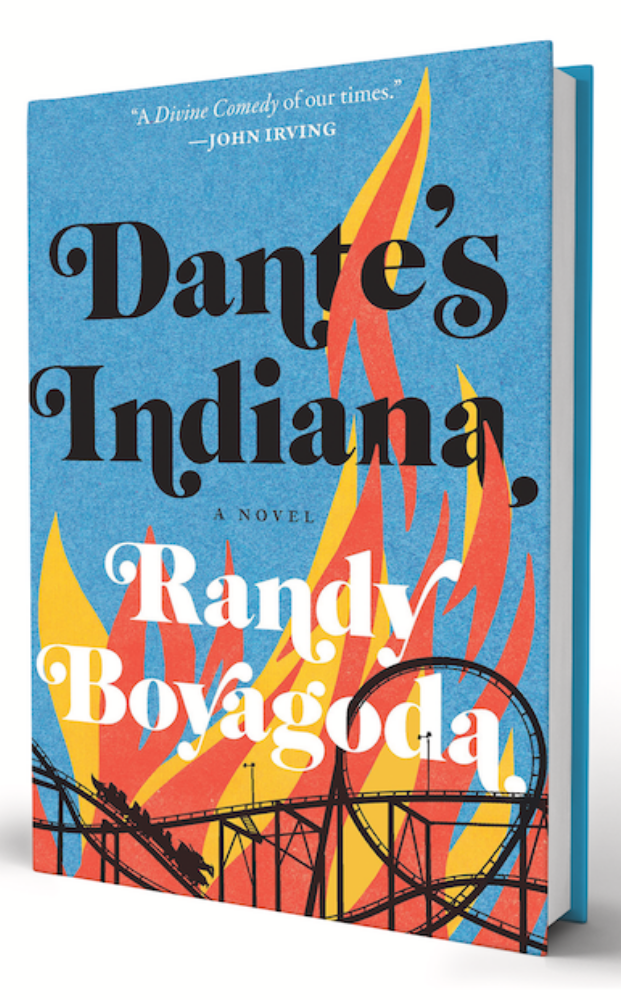

Messiness is pretty much a given in the trilogy’s second book, Dante’s Indiana. Back in Toronto from Dragomans, Prin is in a difficult situation at home, his wife having decamped with their four daughters to her mother’s in Milwaukee. Life is complicated at his former university, too, which has been converted into a residence for active seniors. Through a long string of events and a pressing need for money, Prin ends up working as an adviser for a Divine Comedy-themed amusement park in Terre Haute, Ind.

More on Broadview:

- Cartoonist Kate Beaton rewrites the classic mermaid tale

- ‘Restaurant Kid’ captures the pain and joy of growing up in your parents’ eatery

- M.G. Vassanji explores what it means to belong in his new essay collection

There’s an uncanny plausibility to the amusement park, where visitors can ride up and down in a three-faced Satan as it eats famous traitors, or hop on a roller coaster representing Geryon, a monster that, Dante wrote, carried him into the eighth circle of hell. “I’m riffing on the phenomenon of creationist theme parks in the United States,” says Boyagoda, who visited three of them as part of his research for the novel.

Overall, though, the tone of Dante’s Indiana feels darker than Original Prin. The rust belt town of Terre Haute is in the grips of the opioid epidemic. Boyagoda’s depiction is an extreme example of collapse, a satirist’s version, but reality has caught up with him. One of the turning points in Dante’s Indiana, the shooting of a young Black man, Garyon Jackson, predated the real-life death of Daunte Wright, who was wrongfully shot by a police officer in Minneapolis when the book was late into production. “That really did seem to intersect with some of the storyline, which I found unsettling,” Boyagoda says. But one thing he’s learned about writing satire is that you keep going.

Which brings us to volume three in the trilogy. Where does Prin go next? “I don’t know yet,” says Boyagoda, “how to be simultaneously faithful to the logic of a paradise novel and faithful to the kind of writing I do. Because some grim philosophical treatise about the eternal beatitude of life in God isn’t the kind of novel that I am willing or able to write.”

“I have two or three starts, one of which is going to catch, like when you’re pulling on a lawnmower,” he says. “I have one in mind now that might be the one.”

***

This article first appeared in Broadview’s September/October 2025 issue with the title “Paradise Laughs.”

Ian Coutts is a writer and editor in Kingston, Ont.