Kyrie eleison. Lord, have mercy.

This was the prayer I offered in the death chamber moments before the state of Texas executed Ramiro Gonzales. Ramiro was convicted and sentenced to death for the 2001 rape and murder of Bridget Townsend, a crime he committed when they were both 18 years old.

You may unsubscribe from any of our newsletters at any time.

His sentence was carried out on Wednesday, June 26.

I was Ramiro’s spiritual advisor. I had also been his friend for over a decade. He called me Mana—a Spanish term of endearment for “Sister.” He was my Mano. Since his death, my heart has been broken. My body feels poised for fight or flight. Time will forever be defined as before Ramiro and after.

Kyrie eleison. Lord, have mercy.

There is a certain macabre ritual that surrounds Texas’ executions; from last visits, to last meals, to last words. Ramiro spent Monday and Tuesday gathering with friends and family. We came in twos following a schedule Ramiro had carefully curated. He knew exactly who to pair together so that everybody would be supported. In his final days, Ramiro’s greatest concern was for those he was leaving behind.

Ramiro wasn’t always kind and caring. He took the life of Bridget Townsend. He kidnapped and raped another woman later in the same year. It is very possible he would have continued on to a whole life of violence if he had not been arrested and ultimately convicted for his crimes. However, once removed from the toxic and abusive environment in which he’d grown up drowning, Ramiro changed.

I never met Ramiro the murderer. There are people who have only ever known Ramiro in that way and I can understand their rage. But the Ramiro I knew was kind. Thoughtful. He had watched my children grow up with curiosity and joy. He obtained the equivalent of a bachelor’s degree from a theological college and had become a peer coordinator within a newly formed faith-based program on death row. The broken, suicidal, and violent 18-year-old boy who committed those terrible crimes died decades ago. In his place, the state of Texas killed a 41-year-old man who loved everybody around him—inmates, guards, penpals, friends, and family. The state’s own psychiatrist even changed his opinion, saying Ramiro would not be a problem if his sentence was commuted to life in prison without the possibility of parole. This reversal of opinion by an expert witness was unprecedented. Ramiro was clearly no longer a “future danger”, one of the prerequisites for receiving a death sentence in Texas.

Kyrie eleison. Lord, have mercy.

Death Row inmates are incarcerated at the Alan B. Polunsky Unit in Livingston but are transported to the Huntsville Unit for execution. After visiting Ramiro in the morning, I made the hour-long trip to Huntsville for what would likely be my last time. It is an oddly beautiful drive. Before I left, I suggested Ramiro look out the window and take in the forest and lakes. “No, they changed the vans, and the new ones don’t have windows,” he said. “I won’t be able to see anything outside.” Ramiro grew up on a ranch and loved the outdoors. Not being able to take in the countryside as he was travelling through seemed poignantly cruel.

More on Broadview:

I met Ramiro at the holding cell outside the execution chamber. For two hours we talked. We prayed. We shared in communion. We sang very old hymns—the only songs of lament and praise we had in common. At one point, a prison employee discreetly handed me a hymn book and I started flipping through the pages. I began to sing, “Were you there when they crucified my Lord?” The words from this African American spiritual rang through the concrete and steel:

Oh, sometimes it causes me to tremble, tremble, tremble.

Were you there when they crucified my Lord?

The tears came. Ramiro wasn’t afraid of death, but he was afraid of the dying process. This has been a common theme for others I have journeyed with toward death, albeit due to illness or age. What if the pentobarbital didn’t work quickly? What if there was pain? I told Ramiro that no matter what happened, just hold on to me. I wondered if I was like a midwife and that his dying (if one can ignore the injustice of it all) was akin to giving birth. Labour is painful. But the only way for the pain and the fear to stop is not to retreat, but to push through. In the end, the reward is so great that the pain is worth it. Ramiro’s understanding of God, life, and death created a deeply held certainty that at the end of everything—at the end of the birth pangs—there would be joy and reconciliation. He would be with God.

Shortly after 4:30 p.m., Ramiro received word from his attorneys that the Supreme Court had denied his claims. The execution would proceed as scheduled. My last minutes with him at the holding cell were filled with words of love for everybody who had cared and fought for him. He asked me to check in on his family and attorneys to make sure they were OK. He asked me to let the guys back at “the row” know what they meant to him. He expressed hope that through his death the family of Bridget Townsend would find peace. And then, I was escorted out. “I’ll see you soon, Mana.”

Over the next hour, Ramiro was offered a final meal and a change of clothes. At 6 p.m., he was led into the execution chamber where IV lines were inserted into his arms. I was in a separate area, checking in with prison employees about the process to come. Everyone at the Huntsville Unit treated Ramiro and me with compassion and respect. I believe what the state of Texas did to Ramiro was evil, but I do not think the people tasked with carrying out his sentence are evil. They are essentially good people with a terrible job to do. There is a cost to everyone involved in taking the life of another human being. Honestly, I wish it was those who make the decisions about who is worthy of mercy—such as the Texas Board of Pardons and Paroles—who are responsible for carrying out the death sentences.

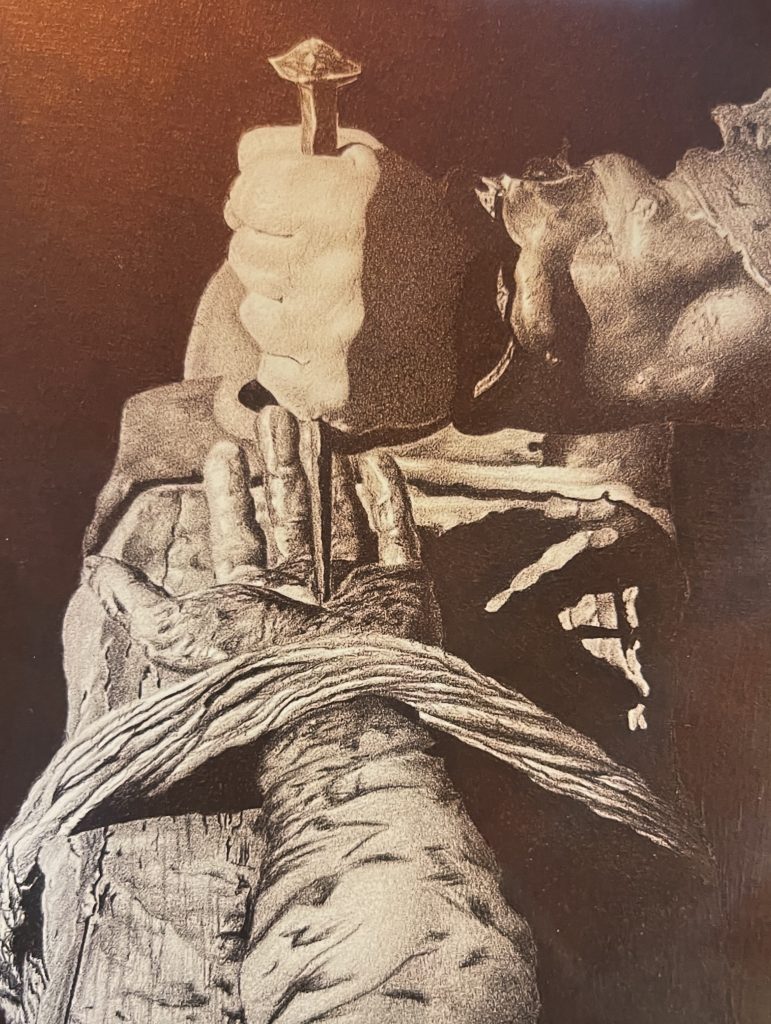

The next time I saw Ramiro he was strapped to the gurney. It is remarkable how much the gurney used for a lethal injection resembles a cross. I sat close to Ramiro’s head, with one hand on his chest and the other stretched towards his arm.

And then, I sang.

Kyrie eleison. Lord, have mercy.

It is a short prayer, but there is a lot of meaning packed into these few words. Lord, have mercy. On Ramiro, of course. But also on the prison staff. On the governor. On the Board of Pardons and Paroles. On me. I was there. I prayed, but I did nothing to stop the death of my friend. I knew I wouldn’t. I couldn’t. Ramiro would never have wanted me to. Lord, have mercy on me too.

Ramiro was then asked if he’d like to give a final statement:

Yes ma’am, to the Townsend Family, I’m sorry I can’t articulate, I can’t put into words the pain I have caused y’all, the hurt what I took away that I cannot give back. I hope this apology is enough. I lived the rest of this life for you guys to the best of my ability for restitution, restoration, taking responsibility. I never stopped praying for all of you. I never stopped praying that you would forgive me and that one day I would have this opportunity to apologize. I owe all of you my life and I hope one day you will forgive me. I’m sorry. Patricia, I’m sorry. David, I’m sorry. To all your family I’m sorry. I just want you to know I love you guys and I lived the best that I could to give it all back. To my family, my friends thank you for all the support every decision I made everything I said in this penal system was based on how it will reflect on you guys. And Bridget, I lived my life for you guys. I love all y’all. To the administration, Warden Dickerson, Hazelwood thank you for being so courageous for making decisions to make this penal system better. You guys are also my goal. It’s why I’ve been better. Giving me the responsibility and the opportunity to become responsible to learn accountability and to make good. Continue to fight the fight especially in your faith. God Bless you all.

After he finished, Ramiro straightened his body, took a breath and said, “Warden, I’m ready.” It was chilling. He said those words with so much conviction, I believe it was one final claim of agency. “You may take my life, but you are not taking who I am. I am ready.” He knew where he was going. It was one of the most Christlike things I’d ever seen.

Ramiro looked at me and said, “I love you, Mana.” As the pentobarbital started to flow through his veins, I sang words from Ramiro’s favourite psalm, Be still and know that I am God. Over and over the notes floated softly through the chamber and hopefully reached his heart. He took seven breaths and then began to snore. With my hand continuing to rest on his chest, I could feel his heart slow and eventually stop. Although he was not pronounced dead until 6:50 p.m., I am certain I could feel the exact moment when Ramiro’s essence left his body. He was gone. He was spirit. He was free.

Kyrie eleison. Lord, have mercy.

It is an incredibly horrible and helpless feeling to hold someone as others work to end their life, knowing there is nothing you can do to stop it. To know we are sharing space with those who may even find some satisfaction in the process. I say this without judgment—what Ramiro took, there was no way to give back. For some in that space, Ramiro’s death marked the end of a 23-year process filled with pain and heartache. For those like me who only knew the best of Ramiro, the grieving started on Wednesday night.

We travelled to a little church outside of town where Ramiro’s family and friends were able to be with his body for 15 minutes. There are no contact visits on death row, so this was the first time his loved ones had been able to touch him since his conviction in 2006. As goodbyes were said, I looked around to take in the scene. In addition to being surrounded by employees from the Texas Department of Criminal Justice, the entire sanctuary was filled with American flags—large flags at the chancel and tiny flags adorning every pew. I wondered what Ramiro would think—emblems of the country that had sanctioned his death surrounding him in what was supposed to be a sacred space. I wondered what Jesus would say: ‘Father, forgive them. They don’t know what they are doing.‘ I suppose it wasn’t the worst thing the state did that day.

Kyrie eleison. Lord, have mercy.

Two years ago, I reflected on a section of The United Church of Canada’s Song of Faith (2006) and its connection to capital punishment:

Because his witness to love was threatening,

those exercising power sought to silence Jesus.

He suffered abandonment and betrayal,

state-sanctioned torture and execution.

Ramiro’s witness to love was threatening. If he could change, come to terms with the evil and harm he both endured and perpetrated, and still find it within himself to love fully and deeply, then the myths we tell about who the monsters are, who is beyond our obligation to care for, and who deserves to live or die would be debunked. Texas would need to acknowledge that rehabilitation is possible—even for those deemed to be the worst of the worst. And if the condemned are rehabilitated, then executing them is not about safety; it is about vengeance. The death penalty has always reflected more on society than those lying on the gurney. No good has come from Ramiro’s death, only more heartache.

Outside the prison, Ramiro’s attorneys, Thea Posel and Raoul Schonemann, gave a statement to the press—a tribute to a man we’d all grown to love:

“Ramiro knew he took something from this world he could never give back. He lived with that shame every day, and it shaped the person he worked so hard to become. If this country’s legal system was intended to encourage rehabilitation, he would be an exemplar.

Ramiro grew. Ramiro changed. May we all strive to do the same.”

If anyone had told me ten years ago that I would one day sing a man to death in a Texas execution chamber, I would have laughed at the absurdity. What happened at the Huntsville Unit last week was, indeed, absurd. I found myself there because violence begets violence. Generations of violence festered, leading to one particular heinous and violent act, which then led to another heinous and violent act carried out by a government who really ought to know better. And on it goes…

There will be a time to rage at this reality. There will be a time where I rejoin the fight to make sure that one day the scapegoating and the killing stops.

But for now, I am in mourning. Ramiro has been lost to the lie that redemption is impossible. My heart is broken open and grief leaks everywhere.

Lord, have mercy on us all.

***

Rev. Bri-anne Swan is the lead minister at East End United in Toronto.