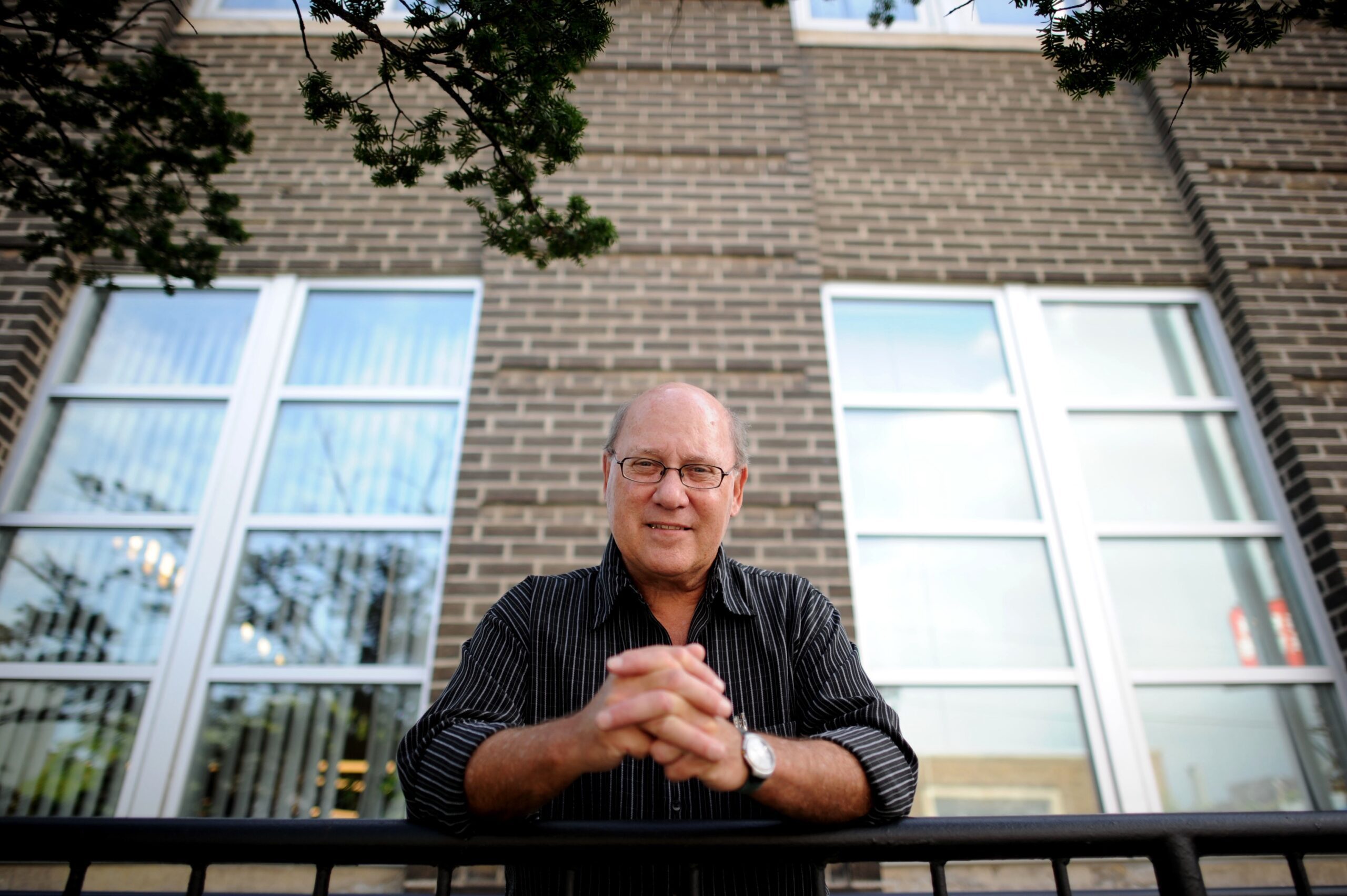

“There’s lots of anxiety surrounding it,” says Ian Grant, recalling how he felt in June 2012 as the moment of his release from prison approached. Anxiety? Not joy or relief after five long years in a federal penitentiary? Grant is speaking to an audience of roughly 200 people gathered at Eglinton St. George’s United in Toronto as part of a series of panels on compassionate justice. Today’s topic is returning to society — no cakewalk, Grant says, especially for long-term inmates like him. “Anyone who says it is, is trying to play the tough guy.”

Coming from Grant, this comment is especially charged. If there’s a tough guy in the room, he’s it. A former Hells Angel, Grant stands an imposing six foot four inches tall and weighs a lean, muscular 240 pounds. Now 39, Grant spent most of his last decade serving the pre-parole and day parole segments of a 15-year sentence for drug dealing and extortion.

You may unsubscribe from any of our newsletters at any time.

“When a guy gets down to the last few weeks of prison, it’s exciting but also scary,” says Harry Nigh, a Mennonite chaplain at the Keele Community Correctional Centre in Toronto, and moderator of the panel. Nineteen years ago, Nigh started a program called Circles of Support and Accountability (CoSA) under the aegis of the Mennonite Central Committee of Ontario. The purpose of the publicly and privately supported program is to help men and women emerging from the Canadian justice system, like Ian Grant, to successfully reintegrate into mainstream society. And reintegrate they inevitably will, he observes: for better or worse.

David Wilson, professor of criminology at Birmingham City University in the United Kingdom, wrote in the Guardian newspaper in 2006 that prison is “performing a huge disappearing trick, sweeping under the carpet huge swaths of the population, hiding them from public view.” But remember, he warned, it is only a trick. “All those who have disappeared will return,” he wrote. “And when they do, none of their underlying problems will have got better; many will have got worse.”

In Canadian prisons, what do those “underlying conditions” comprise? Thirty-six percent of federal inmates have mental health issues. As many as 80 percent are drug users. Sixty-five percent have no high school education. But the key statistic to remember is that 85 percent of inmates now in our jails will eventually be back on our streets.

Disputing the prevailing mythology that building more prisons will make us safer, Wilson concluded, “Prison does not make a community safer. The opposite: prison ultimately contributes to making it more dangerous.” Therefore the job of doing what prisons don’t do, says Nigh, falls to the rest of us.

If there’s one thing that rivals the misery of being in prison, it’s the anxiety around getting out. The prospect of failure looms large. Nigh has seen a lot of people like Grant with the post-prison jitters. “They feel everybody knows where they’ve been, that they have a brand on their forehead saying ‘Prisoner.’ They have no skills. They’re leaving friends behind. They’re leaving a culture behind, with its own rules, its own ethos. They’re coming back to what they call the ‘Square John’ culture. How do they fit in with that? Especially if they’ve done a lot of time.”

Grant often gets the feeling that time has passed him by. “Technology has moved so fast,” he marvels. “I was aware it was happening, but unless you participate in it, you really don’t get it.” The freedom to set your own course is also a shock, he adds. “For five years, every waking moment was regimented. You simply lose the knack for making decisions on your own.”

With someone else looking after the details for him, Grant was free to think about some of the bigger questions, like what exactly was the point of his doing time. “We have to ask ourselves: what is the ultimate goal?” he says.

This is a question on many lips as the federal government seeks to pour more money into bigger prisons, keeping more inmates locked up longer. A recent story in Walrus magazine (“Rough Justice,” May 2013) explores just this issue, coming up with two answers: “an eye for an eye” and “turn the other cheek.” Author Daniel Baird shows that the system has a retributive side, holding that offenders need to be punished. There is also a restorative side. The system claims to want to help offenders mend their ways and re-enter the mainstream. Punishment versus rehabilitation: Baird concludes that the Canadian justice system is an unsuccessful “hodgepodge” of both.

Harry Nigh has his own take on this apparent ambivalence. While the mandate of the Canadian corrections system may pay lip service to rehabilitation, the budget favours retribution, he says.

Federal corrections expenditures totalled approximately $2.375 billion in 2010-11, a 43.9 percent increase since 2005-06, and were projected to rise to $3 billion in 2011-12. The annual average cost of keeping a federal inmate in prison has risen from $88,000 in 2005-06 to over $113,000 in 2009-10. “That’s a lot of money to keep people locked up,” Nigh observes, “but when they hit the community again, the money dries up.”

Mary Sanderson knows how that looks from the front lines. A member of Bloor Street United in Toronto, Sanderson volunteers at Okimaw Ohci Healing Lodge near Maple Creek, Sask. Okimaw Ohci is a medium-security institution, one of a handful of prisons designed specifically for Aboriginal women.

Sanderson leads art-therapy workshops, travelling to Maple Creek every three months, staying for three weeks at a time. For the women in her classes, successful reintegration is almost unimaginable. While the correctional service budget has ballooned, programs designed to help women overcome their issues and learn new skills have been cut, she observes. “When I first started there in 2009, new arrivals had to spend their first 90 days in the kitchen preparing the noon meal. Since many of them had been living on the streets since age 12, they knew nothing about meal planning or nutrition or cooking, so this was a godsend.” Sanderson says that’s all gone now with the federal government cuts. “Now a lot of them just retire at noon to their own unit and make a jam sandwich. They don’t know any better.”

The Correctional Investigator, a federal watchdog on prison conditions, seems to confirm what Sanderson claims. The agency’s 2011-12 annual report points out that Correctional Service Canada is responsible for providing programs “that contribute to the rehabilitation of offenders and their successful return to the community.” These programs work well if inmates get to experience them, the report says, but a snapshot of participation by male inmates on Feb. 1, 2012, showed that in the seven institutions surveyed, only 12.5 percent of offenders were enrolled in a core program, while the number of offenders on a waitlist for programs at those same institutions exceeded 35 percent. “These statistics are not very encouraging,” the report concludes.

If prison life fails to equip men and women for life in the mainstream, post-prison services like halfway houses, treatment and advocacy programs are in even worse shape. “I can’t speak to the federal government’s bottom line,” Nigh says, “but I see what I see. Although the prison population is growing, the chaplaincy is frozen. No new hiring. Effectively a cut. Contracted services with psychologists have also been significantly reduced, at least in my district.”

The failure of the system to prepare convicts for reintegration has inevitable consequences, according to Greg Powell, a divinity student at Emmanuel College in Toronto. Last year, as part of his program, Powell spent eight months leading a book club for ex-convicts under the auspices of the Mennonite Central Committee of Ontario, the agency that sponsors Nigh’s CoSA programs. The experience left him with the strong sense that, in answer to Ian Grant’s one big question, the Canadian justice system is dangerously confused about its ultimate goal.

“I was shocked at how little help there is for getting people reintegrated, especially when government emphasizes safer streets. When we release somebody from prison, the streets are more dangerous because that person doesn’t have the help they need to reintegrate,” Powell says. “They haven’t learned better behaviours in prison. . . . They’ve learned behaviours that are even more anti-social. The penal system we have right now, in my opinion, just encourages more offence.”

Recidivism rates confirm what Powell’s experience and intuition suggest. Ten-year-old figures from Corrections Canada say that, at the time, 44 percent of all offenders released were reconvicted within their first year of freedom. No one argues that things have improved.

A justice system confused about its purpose, spending more money to less effect, arguably promoting criminal behaviour instead of discouraging it: what is to be done? Change the system or, as Walrus writer Daniel Baird unexpectedly suggests, work outside it. “Prison is an improbable place for rehabilitation, in part because it focuses exclusively on the offender,” he writes. “Crime is, as [Harry] Nigh insists, a community problem, and the community needs to participate in the solution.”

Nigh’s Circles of Support and Accountability programs, first set up in 1994 in Hamilton, represent a form of restorative justice. They involve a committed group of trained volunteers from the community (four to six for each offender or “core member”) who meet regularly to help deal with practical issues, provide emotional support and assist the core member in finding socially positive ways of living. The circle, in short, provides the kind of community most people take for granted.

Many experts argue it’s the most effective way to reintegrate offenders. Now spread across the country and supported by government grants of more than $7.5 million over five years, support circles boast significant improvements in recidivism. In a three-year study, CoSA participants convicted of sex offences were found to reoffend at rates between 70 and 83 percent lower than a comparable group of offenders who did not benefit from a CoSA program.

Though proven effective, the circles are labour intensive and wholly dependent on volunteers. Nigh tosses the ball to us. “How do we welcome people back?” he asks. “That’s the challenge for the faith community and the community at large.”

Ian Grant has benefited from Nigh’s restorative justice program. (“Harry’s the most under-appreciated guy in the criminal justice system,” he says.) Though still in a halfway house, Grant has created work for himself by starting a painting company. He has an apartment, a partner and family who support him, and he’s “chipping away” at an online degree from Athabasca University that would give him the credentials to become a counsellor himself. On a day pass from prison, Grant visited a tattoo parlour to have the date tattooed over the insignia of his old criminal community, signifying that his association with them was now over. Thanks to Nigh’s circles of support, he’d found a new, better community.

***

This story first appeared in The United Church Observer’s July/August 2013 issue with the title “Hard time on the outside.”