Canada’s western Arctic is warming up twice as fast as the rest of the world, ravaging coasts and interior landscapes in the Yukon and the Northwest Territories. That’s because the permafrost that’s propping up the Arctic is thawing, causing the ground to subside. The more ice in the permafrost, the more severe the subsidence, causing coastal cliffs and rolling tundra alike to collapse. One of the most dramatic changes is the rapid proliferation of crater-like thaw slumps, which can measure up to a kilometre wide.

Steve Kokelj is a permafrost scientist with the Northwest Territories Geological Survey (NTGS). He has studied permafrost thaw for the past two decades, including the last five with the NTGS, concentrating much of his field work on the territory’s Peel Plateau, in the Richardson Mountains, and the Mackenzie River Delta. “The idea of having or needing permafrost scientists is relatively new,” says Kokelj. “But it’s growing as the consequences of thaw become increasingly relevant to understanding climate-driven environmental change and developing an information base to support northern community adaptations to change.”

You may unsubscribe from any of our newsletters at any time.

More on Broadview: Thawing Arctic permafrost seems like a distant threat. It’s not.

To gather data that will help northern people predict future changes and make evidence-based decisions as to, say, which areas to avoid when planning the construction of new homes, airstrips and roads, Kokelj and other scientists track landscape changes over time. One way to do so is by aerial surveys of eroding coasts, landslides and thaw slumps via helicopter and drone. Time-lapse videos are also taken to record, for instance, the progression of a thaw slump over a season or a storm surge in a flood-risk zone over a single weather event. Other tech tools that field researchers use to monitor permafrost thaw include heat-sensitive cameras, ground-penetrating radar and fluxmeters that keep tabs on the concentration of greenhouse gases in the air. Comparing data from one field season to the next provides an overview of changes that are happening as the result of climate warming.

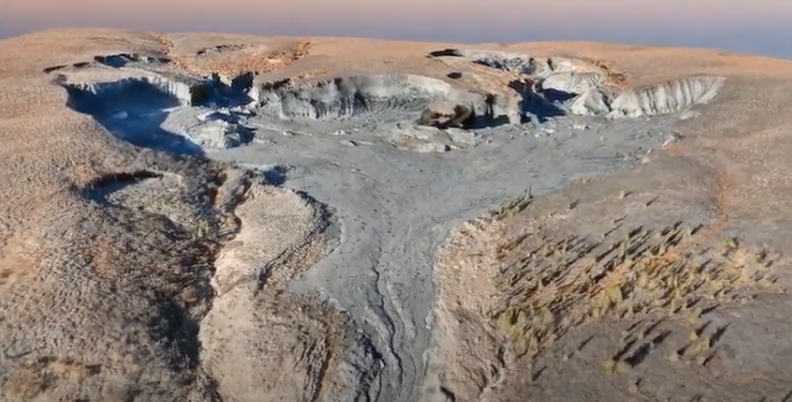

Depending on soil composition and ice content, when permafrost thaws, it can cause huge swaths of the landscape to collapse. This is happening in the Willow River watershed in the Northwest Territories. “The rapid changes in parts of northwestern Canada are pretty disconcerting, but they’re explainable and at least regionally predictable,” says Kokelj. He tracks the progression of thaw slumps near the Willow River using images from drones, satellites and time-lapse cameras. “The permafrost materials in northwestern Canada are ice-rich, fine-grained tills that have a tendency to flow once thawed and saturated,” he says, explaining there are hundreds of such slumps in the watershed alone, all gushing thawed mud and silt. This drone survey shows a 980-metre-wide mega slump and its “debris tongue,” the drainage of mud that is unleashed as the slump recedes from its cliff-like headwall.

When thaw slumps expand, they set in motion previously frozen soil, silt and mud. But as the headwall of these active slumps keeps receding, they can also affect bodies of water located above, or in front, of them. This time lapse shows how a small lake near Fort McPherson, N.W.T. was drained when the headwall of a nearby thaw slump gave way — like pulling the plug in a bathtub — flushing a massive amount of sediment downstream. The environmental consequences of these mud flows on rivers and lakes downstream are still being investigated, but locals and scientists alike are concerned the sediments may contain mercury that was locked away in the permafrost, which can contaminate drinking water and the fish that people depend on.

Like the rest of the Mackenzie River Delta, Peninsula Point, southwest of Tuktoyaktuk, is undergoing dramatic landscape alterations due to the climate crisis. No wonder, then, that it’s a good site for scientists to study what happens when the permafrost thaws. While some researchers, including Paul Mann in our September cover feature, focus on the environmental impact of permafrost thaw, such as the release of carbon dioxide into the atmosphere, others record the physical processes behind landscape collapses. To understand what triggers a thaw slump, for instance, Michael Lim, a professor at Northumbria University in England, uses ground-penetrating radar, thermal imaging, temperature readings and aerial and time-lapse photography. After setting up a time-lapse camera in one of the thaw slumps on Peninsula Point, Lim was able to capture the cliff-like headwall dripping with mud and water released from ground that had been frozen for thousands of years. Combined with other data collected over three field seasons, the time lapse adds a layer of information to Lim’s other measurements.

[Credit: Video courtesy of Michael Lim, Northumbria University; and Dustin Whalen, Natural Resources Canada; with support from the NERC Arctic Office and permission from Parks Canada]

When a storm blew in over Tuktoyaktuk in early August 2019 — well ahead of the usual start of the fall storm season — a team of scientists tracking the impacts of the climate crisis on the Beaufort Sea coast was present to record different aspects of the weather event. This time-lapse footage shows a storm surge (sea water pushed by the wind over land) that ensued. As storm surges increase in frequency and reach, causing flooding in the hamlet, local knowledge holders and scientists are collaborating to map flood-prone areas. The data will be used to predict the extent of future storm surges and flooding and the potential damage to homes and infrastructure, as well as to make science-based decisions on relocations, construction and infrastructure projects in the years to come.

[Credit: Video courtesy of Michael Lim, Northumbria University; and Dustin Whalen, Natural Resources Canada; with support from the NERC Arctic Office and permission from Parks Canada]

***

Susan Nerberg is a writer in Montreal.

I hope you found this Broadview article engaging. The magazine and its forerunners have been publishing continuously since 1829. We face a crisis today like no other in our 191-year history and we need your help. Would you consider a one-time gift to see us through this emergency?

We’re working hard to keep producing the print and digital versions of Broadview. We’ve adjusted our editorial plans to focus on coverage of the social, ethical and spiritual elements of the pandemic. But we can only deliver Broadview’s award-winning journalism if we can pay our bills. A single tax-receiptable gift right now is literally a lifeline.

Things will get better — we’ve overcome adversity before. But until then, we really need your help. No matter how large or small, I’m extremely grateful for your support.

Jocelyn Bell

Editor/Publisher

Just want you to know that I subscribe to Broadview in magazine form. It’s s terrific publication. So when people on Facebook get asked to subscribe, you should have 2 options for answers: “No thanks” or ” I’m already a subscriber”…..That way you know we are already subscribers.