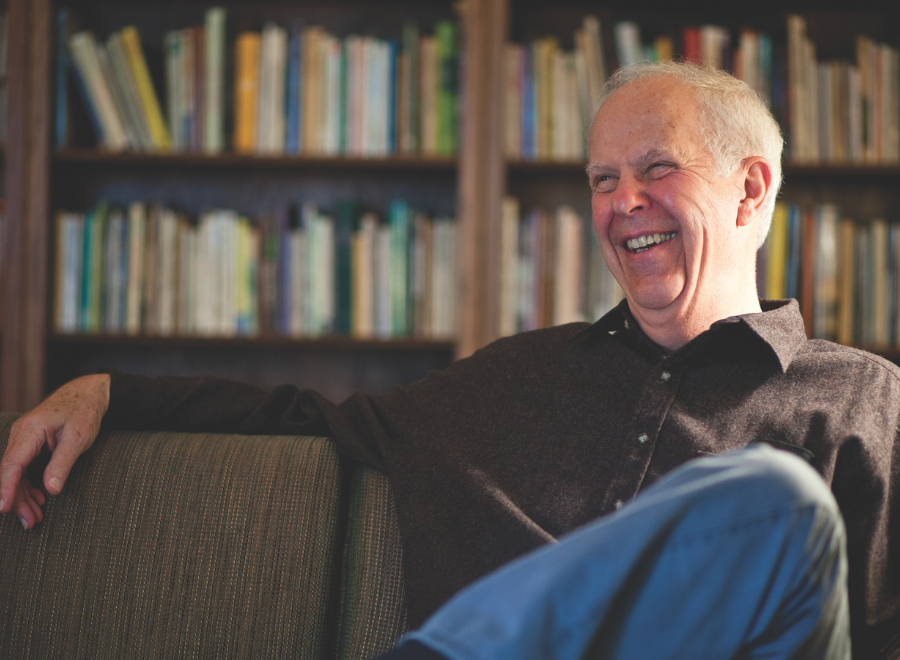

Parker Palmer, educator and author, is the founder of the Center for Courage & Renewal in Seattle. He talked about democracy, the “mentality of scarcity” and revitalizing mainline churches in conversation with Alicia von Stamwitz.

ALICIA VON STAMWITZ: You’re well known for your works on spirituality, leadership and educational reform. Tell me about your most recent book, Healing the Heart of Democracy.

You may unsubscribe from any of our newsletters at any time.

PARKER PALMER: I think this new book brings together a lot of threads that I’ve laid down in the past and takes me full circle to where I started as a community organizer in Washington, D.C. One of the points that I’ve tried to work on for a long time is that in both our educational and our religious institutions, we have a bad habit of making people spectators to some sort of action on stage. We treat people as empty vessels to be filled with the knowledge of experts, whether that expert is the pastor, the priest or the professor. And this results in a wound that I think a lot of people carry. They don’t feel they have a voice, or they don’t believe they have a capacity to speak it. They don’t have a sense of agency. So I think one of the great tasks is to heal that wound, to help people recover their voices and sense of agency, and to help them believe they have something worth saying.

AVS: What was the genesis of the book?

PP: I started writing it in 2004 or 2005 because I was in a psychological hole. I was in a lot of despair myself about what was happening in our country, about our inability to talk to each other, about democracy going down the tubes. And it was actually a period of depression for me. Part of my journey involves three major experiences with clinical depression, and one of the things I learned in my previous bouts was that if you get a little bit of energy, you have to do something proactive related to what’s causing the depression. Becoming proactive can be therapeutic, can be life-giving. So I started writing this book. I basically argue that what we call the politics of rage [in the United States], if you look at it more deeply, is in fact the politics of the brokenhearted. I believe that there’s heartbreak across the political spectrum, all the way to the radical ends.

AVS: How does heartbreak become rage?

PP: One of the axioms I came to while writing this book is, “Violence is what happens when people don’t know what else to do with their suffering.” I think that axiom applies on every level of life. When individuals don’t know what to do with their suffering, they do violence to themselves or others near them; substance abuse would be an example, overwork at its extremes another example. When nations don’t know what to do with their suffering, as after 9/11, they go to war. They hit back. I think it’s pretty evident by now that the actions we took because we didn’t know what else to do with our suffering after 9/11 have escalated the tension. Fear has been manipulated in dozens of different ways to justify the doing of more violence.

AVS: Your comments on fear and manipulation remind me of something else you’ve written about: the “mentality of scarcity.” Can you explain what you mean by that?

PP: Our institutions teach a mentality of scarcity in order to corner the market on whatever it is that they’re selling. Our educational system basically says, “You’re not smart unless we certify you as smart.”

The church, historically, has been in a similar game. The church has basically said, “You can’t have God unless you come through us. You can’t have salvation unless you come through us. You can’t have a good life unless you come through us. You can’t get this stuff from secular sources, and you can’t have it from competing denominations, either. We branded our product and made it ours alone; so if it ain’t Missouri Synod Lutheran, or if it ain’t conservative Catholic with the Latin mass, you don’t have it.” If you can convince enough people of that, then the church stays in business. It’s an institutional deformation.

AVS: What’s the fix?

PP: It’s right there in front of our eyes, what I call “secrets hidden in plain sight.” And every institution has them. The students that sit in our classrooms are not empty vessels. The parishioners that sit in our pews are not people who know nothing about the faith journey. But there’s an institutional blockage when it comes to releasing or recognizing these assets.

I once worked with a group of Episcopal churches in Texas. They were mostly small, rural churches, and collectively they felt like they were dying. Their budgets and membership had fallen off. I listened for a while, and then I said, “You know, it’s interesting to me that the only books you’re keeping have to do with dollars and numbers and members. Can you imagine another kind of book that has to do with the resourcefulness of the people in your congregations, the gifts they have to offer, the needs of the communities they serve in, and how those gifts and those needs might intersect?” I said, “You could actually do an inventory of that.”

So this group of churches started doing that, and what was interesting is that over the next few years, they experienced some growth. I mean, they’ll never get back to where they were, but when you stop counting money and start counting life, you get more life. And people are more attracted to churches that do this kind of very human-scale stuff, helping each other in simple, down-to-earth ways.

AVS: What’s preventing more churches from trying this kind of approach?

PP: I think part of the problem — and this is a harsh metaphor, but I think it’s true — I think a lot of churches can be likened to tour buses of the Holy Land. Can I say this in print?

AVS: You can say anything you want.

PP: So, people get on the bus, and then the driver gets up there — that’s the minister, the priest — and he has this microphone in his hand, and he says, “Now, everyone, look out the window on your right: that’s Jesus; and there are the disciples; and now there’s the story of the loaves and fishes on your left, and I’ll explain to you what all this means. We’re not getting off the bus, because it’s dangerous out there.”

There are a lot of people who are just glad to stay in their seats and make sure the windows are shut and the bus door is locked. It’s great, because they get to see the Holy Land, and they get to say, “I’ve been there.” But there are a certain number of people who say, “The next time I go, I want to live with a local family, I want to walk around under my own steam and really experience the place.” They want a full-body immersion in something that the church helpfully introduced them to, because it’s not enough to stay on the tour bus.

I think the question for a lot of churches is, “Do we want to keep running tours of the Holy Land, or do we want to be a congregation in which we prepare people to put stuff in their backpack, learn a new language and hook up with locals so they can be there themselves?” And then they can come back and tell us what they’ve seen and what they’ve done — which is, by the way, kind of how Jesus operated.

***

This story first appeared in The United Church Observer’s November 2012 issue with the title “The church has basically said, ‘You can’t have God unless you come through us.’”