Bustling city streets rendered desolate by lockdowns and stay-at-home orders. Exhausted health-care workers doing their duties while cocooned in layers of PPE. Workmates and loved ones trying hard to sustain connections via glitch-ridden video chats. And anti-maskers in angry mobs decrying it all as a hoax.

In the Same Breath, a bracing new documentary by One Child Nation director Nanfu Wang, is full of images of a world in crisis, images that are striking, haunting yet inevitably familiar, too.

You may unsubscribe from any of our newsletters at any time.

Though the particulars may vary from place to place, certain sights have come to define life in the pandemic era. But our familiarity with these images doesn’t necessarily bring us any closer to understanding how the world got here and how we’re trying to get by. Wang’s film is one of several new documentaries that strive to dig deeper, to chronicle and investigate what’s not only the biggest story of any of our lives but one that continues to unfold in unpredictable ways.

More on Broadview:

- In ‘Shadow Life,’ an Asian elder isn’t a victim. She’s the hero.

- Conspiracy culture and the power of compassion

- Coronavirus fears stigmatize Chinese Canadians yet again

Providing a wider view — with more insight and artistry than you get from late-night doomscrolling — can seem nearly impossible when things are changing so fast. Yet the makers of many recent docs about the pandemic are not so easily daunted. In the Same Breath took the Grand Jury Prize at Sundance in January before winning more acclaim at festivals worldwide. At Hot Docs in Toronto, Wang’s film was part of an extraordinary trio of pandemic-themed films, alongside Wuhan Wuhan by Chinese-Canadian filmmaker Yung Chang and Viral by the Tel Aviv-based team of Sagi Bornstein and Udi Nir. The creators of all three films move beyond rapid-fire reportage and quick hits to offer more complex, more nuanced and ultimately more human takes on these times.

It may help that they’re all part of this story, too. In the early moments of her film, Wang is remarkably frank about her fears as she tries to secure her own family’s safety. The director — born in China and now based in the United States — had left her two-year-old son to stay with her mother in Jiangxi province for the lunar new year in January 2020 while she and her husband attended the Sundance festival in Utah, unaware of China’s looming lockdowns. Her husband was able to retrieve their son, and she knows how lucky they were to evade the kind of painful separations that soon became common.

Since she couldn’t be in Wuhan herself, Wang enlisted a variety of camera people to capture what was going on, despite official efforts to restrict what could be filmed. The medical workers in Wuhan who tried to publicize the crisis on social media became the first in a series of whistleblowers who’d be silenced and punished. Their crime according to the pre-lockdown news reports? “Spreading rumours about an unknown pneumonia.”

Wang’s film is steeped in anger as the painful toll of the outbreak on families and healthcare workers is compounded by the Chinese government’s determination to essentially rewrite history as it was happening. (The number of people in Wuhan who died of COVID-19 could have been over 10 times the official count, she discovers.) But just as the city’s empty streets and overwhelmed hospitals eerily foreshadow scenes soon to be repeated worldwide, so too do the Communist party’s efforts to control information anticipate other governments’ attempts to manage perceptions and deflect responsibility. A montage in which former U.S. President Donald Trump ridicules the threat before assailing the “China virus” is a dispiriting reminder of the misinformation and xenophobia that spread as perniciously as all those tiny droplets in the air.

More than anything else, Wang’s film emphasizes the importance of honouring the experience, sacrifice, and grief of the people most directly affected by the crisis. The same goal drives Wuhan Wuhan, an equally powerful account of the original outbreak. Like Wang, Yung Chang assembled the film from abroad after acquiring hundreds of hours of footage shot during the city’s lockdown. The result is a series of intimate portraits, ranging from a hospital’s emergency room chief to a tireless nurse to a factory worker who chauffeurs essential workers. (The latter must also tend to his very pregnant and often hilariously sarcastic wife.)

What most interests Chang are the quieter expressions of care and connection that sustain us through challenges that may seem impossible. “Ordinary people suffer the most in disasters like this,” one of the driver’s passengers ruefully notes. Yet Chang’s film demonstrates how there’s nothing ordinary about the kindness we can still offer to each other.

Wang’s and Chang’s achievements seem even more remarkable when you consider that both filmmakers had to rely on other people’s footage. Many documentarians have resorted to similarly unconventional tactics due to their inability to go out and find their stories first-hand. For their kaleidoscopic vision of the pandemic in the eyes of Gen Z filmmakers, Bornstein and Nir built Viral out of video blogs and other posts on platforms like YouTube and Instagram. The approach is entirely fitting: well before the pandemic turbocharged our screen addictions, young people had already made social media their preferred means of experiencing the world.

What’s interesting is seeing the range of personal reactions as the film’s seven main subjects face restrictions on the freedoms they take for granted, disrupting not just their plans but also their careful maintenance of their personal brands. That’s especially true for the travel vloggers like Shakir, a garrulous young man from India whose trip on his beloved motorcycle ends with him alone in a COVID-19 ward.

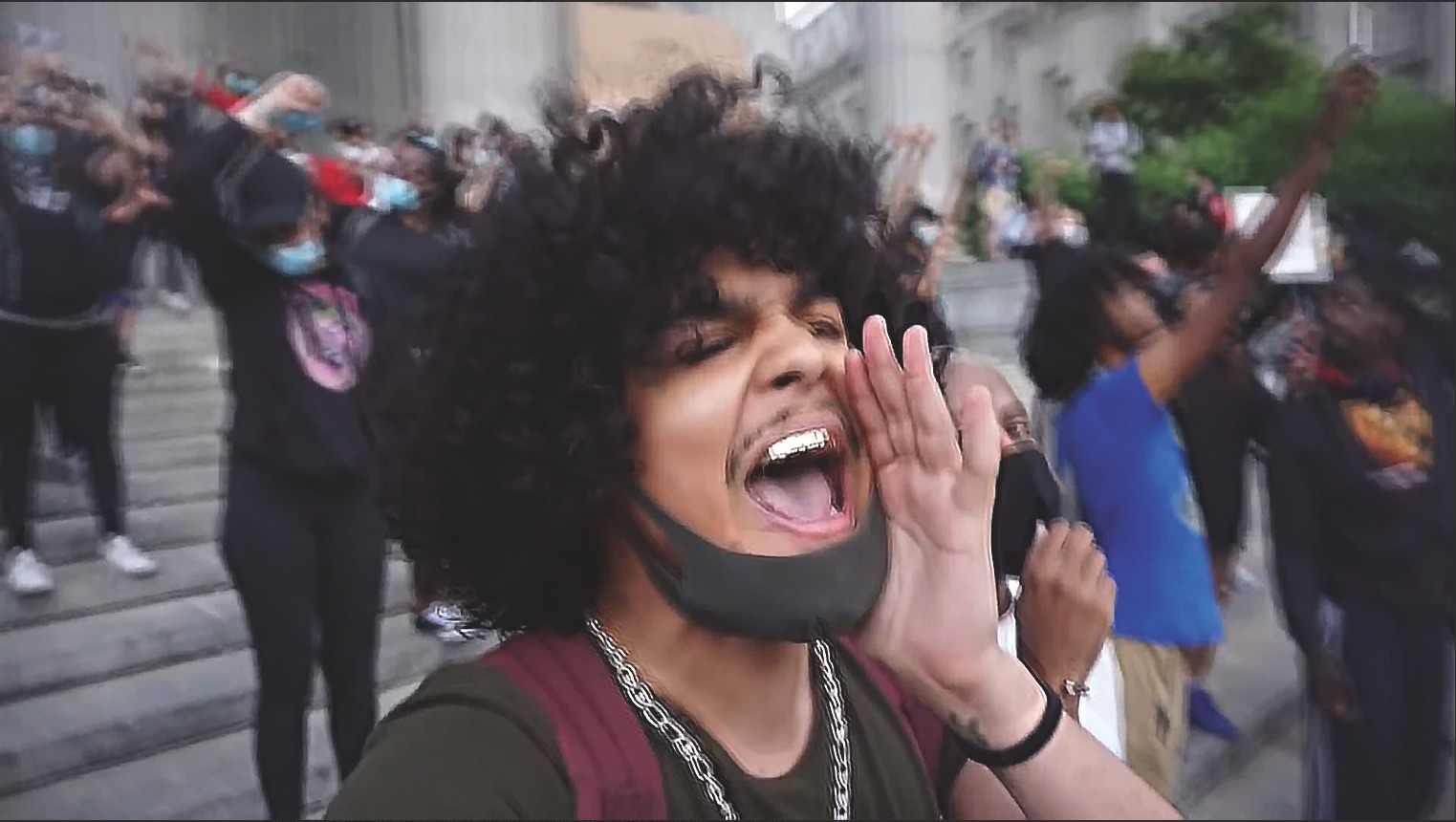

As the lockdown spring gives way to the summer’s protests for racial justice, the emphasis on individualism that’s part and parcel of social media is replaced by a drive for collective action in the face of overlapping crises. Yet a catch-22 also emerges as the film’s subjects, who earn their livelihoods by keeping viewers engaged, begin to question the demands of self-exposure. The most successful YouTuber here, Nathaniel wonders if he’s made “a deal with the devil” by surrendering so much of himself to his subscribers.

The tired, bewildered faces of all these young people as they express their despair to their cameras can seem like another variation on a tragically familiar sight. But like so many of the images captured in Wuhan Wuhan and In the Same Breath, they gain depth and power thanks to the understanding and empathy these films generate.

***

Jason Anderson is a writer, critic and film programmer in Toronto.

This story first appeared in Broadview’s September 2021 issue with the title “Viral footage.”