Tara Hills didn’t consider herself a conspiracy theorist. She was just a young mom: a little tired and, increasingly during those early parenting years, very worried — especially by what she was hearing about vaccinations from other moms in the neighbourhood.

“There were some friends in my circle who were expressing concerns. They’d heard that maybe it wasn’t safe. Maybe it wasn’t necessary,” recalls the churchgoing, home-schooling mother of nine from Arnprior, Ont., a small riverside town in the Ottawa Valley.

“I didn’t actively go looking for [anti-vaccine] information,” Hills now says. “It was just sort of trickling into my mind, into my subconscious.”

The seeds of doubt were planted on the playground. But they flourished online, where Hills discovered a community who shared, and stoked, her fears. This was 13 years ago. Vaccine worries weren’t new — people have been suspicious ever since the smallpox vaccine was introduced in the early 1800s. But they were growing more common thanks to a now-debunked — but still influential — study from 1998 that falsely linked the mumps, measles and rubella vaccine with autism. With the arrival of social media and blogs, vaccine skepticism became especially contagious. Facebook’s algorithm allowed vaccine misinformation to be injected directly into parents’ newsfeeds while visually reducing authoritative sources to the same level as pseudoscientific ones.

For many mothers, the intimacy they felt in online gathering spaces like mommy blogs and message boards led them to trust their anxious peers more than scientists, doctors or other experts. Together, these moms came to suspect the government, the media, academia and the scientific establishment had been bought off by the pharmaceutical industry to cover up the supposed dangers of vaccines. These conspiracy theories would metastasize into wild allegations of vaccine-refuser detention camps, forced vaccinations of every person on the planet and even comparisons to Nazi Germany.

While Hills didn’t believe every claim hardcore anti-vaxxers were making, she became concerned enough to stop vaccinating her children. “The thing with hesitancy is it doesn’t take much, especially when you’ve got strong, powerful things like fear and children involved,” she says. And besides, “It wouldn’t be the first time Big Pharma had lied to you,” Hills remembers thinking. “So, it was very easy to believe that narrative.”

Hills thought what she was doing was healthy, safe and reasonable. It wasn’t. And while she would eventually realize that and schedule a trip to the doctor for her kids to get their shots, this would happen too late. Before the appointment, her oldest daughter contracted whooping cough on an outing. Soon all her children had it. “I totally made a mistake, and my kids [were] paying for it,” she says.

More on Broadview: Why the pet rescue business is buyer beware

Now, Hills is helping health-care workers, immunization experts and social media specialists to better understand why people are increasingly falling for anti-vaccine conspiracy theories. In 2018, 140,000 people died of measles worldwide, leading the World Health Organization to declare vaccine hesitancy a top 10 global health threat. The following year saw measles outbreaks all around the world, including in eight provinces and territories as well as 31 American states — two decades after both countries declared the disease eradicated.

United by a rejection of official evidence, a distrust of experts and a fear of sinister motives, the new anti-vax movement is just one example of the explosion of conspiratorial thinking that’s emerged in this millennium. Conspiracies have ascended into the mainstream, creating what the New York Times has called “a parallel reality unrooted in fact” fuelled by “our deeply poisoned information ecosystem.”

Some of the theories in circulation, like the ideas the Earth is flat, the moon landing was staged or Facebook CEO Mark Zuckerberg is a lizard alien, are relatively harmless. Others have been declared domestic terrorism threats by the FBI. The “Pizzagate” theory, which alleges former U.S. presidential hopeful Hillary Clinton ran a Satanic pedophile ring out of a pizza restaurant, was believed true or possibly true by 46 percent of those who voted for U.S. President Donald Trump. It inspired a real-world shooting in 2016 and an arson in 2019.

And Pizzagate’s successor, “QAnon,” which warns of a so-called deep-state effort to overthrow Trump, has led to an attempted kidnapping, a police standoff at the Hoover Dam and a murder. It’s so prevalent that more than 20 current or former Republican congressional candidates have reportedly endorsed or promoted QAnon. According to the FBI, “these conspiracy theories very likely will emerge, spread, and evolve in the modern information marketplace, occasionally driving both groups and individual extremists to carry out criminal or violent acts.”

How dangerous could these sorts of theories potentially be? Very — when they trade in and amplify damaging stereotypes about religious and ethnic minorities. Ground zero for the modern conspiracy movement is The Protocols of the Elders of Zion, an infamous forgery from the early 1900s purporting to show a cabal of Jews conspiring to control the world. This fake news forerunner helped justify Russian pogroms, fuelled the Holocaust and became the source code for anti-Semitic and “white genocide” theories still inciting hate and violence today. Similar conspiracy theories motivated recent mosque attacks in Quebec City and Christchurch, New Zealand; synagogue massacres in Pittsburgh and Poway, Calif.; and a shooting at a Walmart in El Paso, Texas, where 23 people were murdered.

Clearly, the new conspiracy culture demands our attention as a pressing safety threat. And yet, as dangerous and racist as many conspiracy theories are, it isn’t helpful to write off every conspiracist as anti-intellectual, bigoted and violent. That wouldn’t be fair to people like Tara Hills, who are led away from the facts even as they sincerely seek them. It also wouldn’t be effective: bombarding conspiracy theorists with insults, or even with facts and evidence, only increases their sense of paranoia and persecution.

A better, more empathetic approach is needed: one that understands the powerful pull of conspiratorial thinking; the vulnerability, fear and good intentions that often give rise to it; and the importance of helping people out of these rabbit holes rather than driving them deeper underground.

_________________________________________________________________________

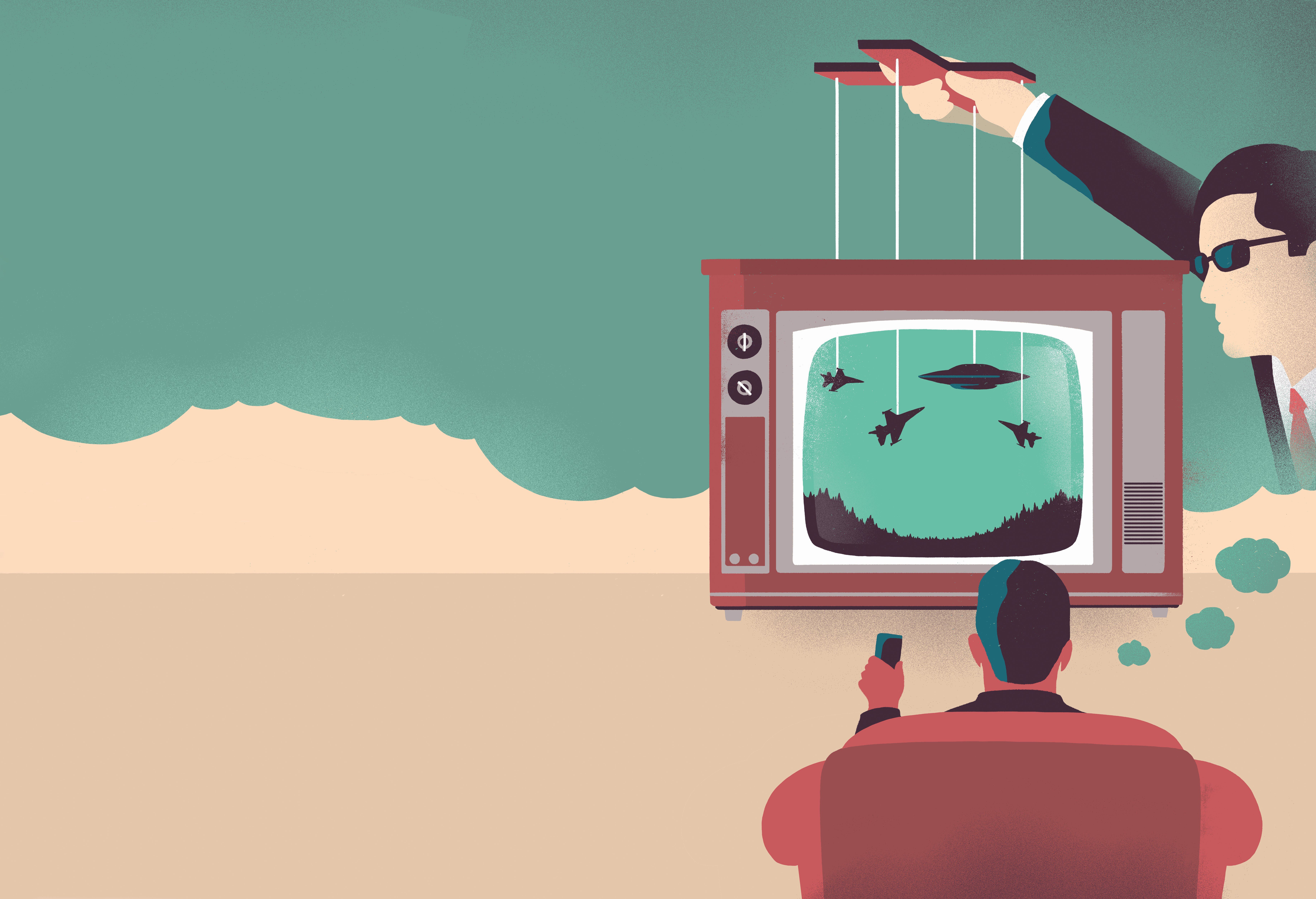

Do you remember The X-Files, the 1990s television show about a government-led alien conspiracy? One of its enduring images was the poster that hung in FBI agent Fox Mulder’s basement office — a fuzzy snapshot of a flying saucer alongside the phrase, “I Want to Believe.” That now-iconic poster captures a sentiment shared by a wider swath of society than just X-Files aficionados. When it comes to conspiracy theories, we want to believe them — for all sorts of reasons.

For one, humans are evolutionarily hardwired to connect the dots: our brains’ exceptional capacity for pattern recognition is how we evolved beyond other species. But this sometimes leads to what’s called apophenia, or the tendency to mistakenly see connections between unrelated things as we try to make sense of a senseless world. After all, even a nefarious and seemingly implausible explanation for a world event is more comforting than no explanation at all. This desire for understanding and certainty is the first of three main drivers of conspiratorial thinking identified in a 2017 peer-reviewed study by British psychologist Karen Douglas.

The second driver Douglas describes is the desire for control and security. Feelings of powerlessness are often a precursor to accepting conspiracy theories — once you reject official narratives, you can start exerting your autonomy and protecting yourself from whatever forces you believe you’re up against. It re-establishes a sense of power and purpose.

The final driver is the desire to maintain a positive self-image, including creating community and trying to right a perceived wrong. This aspect was corroborated by Mick West, author of Escaping the Rabbit Hole: How to Debunk Conspiracy Theories Using Facts, Logic, and Respect. He’s spent years interacting with conspiracy theorists, and says their obsession often comes from concern for others. “People who believe in chemtrails,” for example, which is the theory that the trails of condensed water left behind by airplanes are a mind-control agent, “think they’re fighting against some kind of evil organization that’s poisoning the Earth,” West says. “So you get this kind of Messiah complex in people who believe in conspiracy theories — they think they’re trying to save the world.”

The desire to understand, the need for control and security, and wanting to right a wrong: these psychological drivers of conspiracy theories are all reasonable traits to have. Unfortunately, these drives can get manipulated by bad actors with ulterior motives who stand to profit from the spread of untrue theories. Conspiracy-prone people are unwittingly leveraged for disinformation campaigns, explains Kaleigh Rogers, a former CBC senior reporter who often covered the topic, “because there’s this framework already set up where you’re cobbling [clues] together to create evidence to support this existing theory that you have.”

Disinformation is the deliberate seeding of untruths with the intention to deceive people and distort public opinion. The term was originally coined by the Stalin-era KGB as dezinformatsiya, and Russian authorities have long weaponized conspiracism to weaken geopolitical adversaries. In the 1980s, their intelligence agencies covertly spread claims that the CIA created AIDS to kill Black and gay people. More recently, they’ve employed social media memes and fake news to increase social divisions and influence elections in countries like the United States.

Republicans in the United States have also used this tactic. Trump entered politics espousing baseless conspiracies about former U.S. president Barack Obama’s birthplace, and has gone on to promote many more theories about Muslims, immigrants, voter fraud and the climate crisis. His defenders shared debunked conspiracies about Ukraine during his impeachment proceedings.

Here in Canada, there’s been a pervasive theory that Prime Minister Justin Trudeau plans to introduce Shariah law or is a secret Muslim. There’s “no evidence to support that,” Rogers notes, “but a lot of people suspect it or are curious about it.” This suspicion and curiosity can then be manipulated for social or political ends by people seeding “evidence” or amplifying these rumours, often online and usually anonymously. The Muslim theory has permeated enough that Trudeau was questioned about Shariah law at multiple town halls last year, with one Regina woman saying ominously, “What do we do with traitors in Canada, Mr. Trudeau? We used to hang them.”

With so many players deliberately pushing conspiracies to further their own ends, it’s not a surprise so many people are falling for them. West, the author of Escaping the Rabbit Hole, explains how many conspiracists he knows have fallen into the culture unwittingly. Rather than seeking out specific controversial ideas or starting from a place of prejudice, their first experiences of conspiratorial thinking often involve watching videos recommended to them by YouTube.

“People tell me they had some spare time, so they were just knocking around on the internet, watching YouTube videos, and happened to watch one that really struck a chord with them,” he says. “They then watched another and another.

They would binge-watch [YouTube] for several days straight — essentially brainwashing themselves — and I don’t think you can really fault them for that.” People are often sucked into conspiracy theories during a vulnerable point in their lives, West adds. Comparing such obsessions to alcoholism or gambling addiction, he says, “Some people might say you’re being weak-willed or whatever, but most people understand that these [addictions] are kind of sicknesses.”

_________________________________________________________________________

You may feel well and still have bad blood. Come and bring all your family.” In 1932, flyers with this message were posted around Macon County in Alabama, promising free blood tests and free treatment by “government doctors.” Six hundred poor Black men signed up, 399 of whom had syphilis, with the rest serving as a control group. But none received treatment, free or otherwise. Instead, they were unwittingly enlisted in a secret American government experiment called the “Tuskegee Study of Untreated Syphilis in the Negro Male.” Even after penicillin became the standard treatment for syphilis in 1947, the public health service withheld it from these men so it could continue studying how the disease affected their bodies. This continued until the 1970s when a whistleblower finally came forward.

As this and many other examples make clear, conspiracies do happen, and that fact complicates the fight against the baseless theories that swirl around the internet.

“Conspiracy is very factual. Conspiracy theory just denotes that it’s supposition, that it could be potentially a thing that’s happened or transpired, or may potentially happen or transpire,” explains Patrick Whyte, who co-owns Toronto’s Conspiracy Culture online bookstore with his partner, Kadina Yu.

“At one point, the JFK stuff was all conspiracy theory, right? Watergate was still conspiracy theory.…Thalidomide. Agent Orange. MK-Ultra,” Whyte says. “So many different things were once considered theory but have since been proven otherwise.”

The desire to understand, the need for

control and security, and wanting

to right a wrong: these psychological drivers of conspiracy theories are all

reasonable traits to have.

Whyte isn’t wrong — governments and corporations have covered up dangerous and illegal activity in the past. Thalidomide was an anti-nausea medication prescribed to pregnant mothers. It deformed their babies, and the manufacturer is believed to have known this for months before pulling it off shelves. Agent Orange, a defoliant used in the Vietnam War, was also claimed to be safe but is now blamed for 14 different diseases. A 1990 congressional report on the coverup was subtitled “a case of flawed science and political manipulation.” And MK-Ultra was a top-secret CIA mind-control program the organization eventually admitted was real. JFK of course refers to the 1963 assassination of U.S. president John F. Kennedy. While the government determined there was no conspiracy and Lee Harvey Oswald acted alone, only one-third of Americans believe that, according to a 2017 poll by FiveThirtyEight.

Government coverups are no less conceivable today. In fact, today’s geopolitical context is especially ripe for abuses of power. “Everything changed after 9/11 in terms of privacy, security and the concentration of power in certain government agencies,” says Richard Syrett, one of Canada’s foremost purveyors of conspiracy and host of Zoomer Radio’s Conspiracy Show and the podcast Conspiracy Unlimited. The war on terror has led to significant curtailments of civil liberties, as well as revelations of government surveillance and war-crime coverups by whistleblowers Edward Snowden and Chelsea Manning, respectively.

In this environment, it’s extremely unhelpful that many news-gathering organizations are failing to fully report important stories, either because they no longer have the budget to do so or because they’ve committed themselves to partisan aims. The result is that people are left with unanswered questions and fall prey to the explanations of conspiracists instead.

Syrett himself was originally trained as a journalist, although he doesn’t call himself that. “I’m skeptical in all things,” he says. “I’m all about the data and the evidence. If someone can present that on one of my [radio] programs or platforms, I’m interested in hearing about it.” Syrett’s programs also cover conspiracy-adjacent topics like the paranormal and extraterrestrials.

It was the media’s failure to investigate what he calls “loose threads” about the 9/11 terrorist attacks that partly drove Syrett to start covering conspiracy theories. Mainstream media outlets lack “intellectual curiosity,” he believes. “They are so dismissive of anything that has the word ‘conspiracy’ attached to it…that they’ve created this huge vacuum that’s been filled by people like me, to a certain extent, but also these so-called citizen journalists — some of whom are great, some of whom are not.”

Much of this “citizen journalism” lives on YouTube. In summer 2018, Time magazine declared “Q,” the still-anonymous figure behind the QAnon conspiracy, one of the 25 most influential people on the internet. While Q discussion has migrated from obscure message boards to mainstream social media, it’s particularly popular on YouTube, where you can find around 150,000 videos on the subject, many topping hundreds of thousands of views.

This reliance on YouTube isn’t a coincidence. Rogers reminds us that the site’s profit-maximizing algorithms direct people down rabbit holes that, in the past, they’d have had to specifically seek out for themselves. “YouTube has been a major player in spreading conspiracy theories,” she says. “The recommended video algorithm…tends to show people more extreme content as they go — so it just keeps radicalizing in a way.” Rogers says YouTube and other social media platforms are trying to tamp down on this, to little avail. “If something is sensational and gets a lot of interest, it’s going to be surfaced more frequently, and then more people will see it and they’ll share it.”

But even as all this disinformation proliferates online, Rogers still believes in the good intentions of those who are getting taken in. “The majority of people want the truth,” she says, but “are not totally sure how to tell it apart.”

_________________________________________________________________________

If people want to know the truth, how do we help them to figure it out for themselves? Hills’ case is instructive. In February 2015, just weeks before her children got whooping cough, Hills received a message on Facebook from a public health advocate. She was a friend of a friend, and she treated Hills with empathy. She offered to answer questions, and she cleared up some of Hills’ misconceptions about peer-reviewed studies and vaccine profit margins. Hills admits she was uncomfortable at first. Disturbed by the “social temperature” surrounding the vaccine debate, and the harassment and judgment anti-vaxxers often face, she had learned not to engage with vaccine supporters. (The anti-vax community has also launched aggressive harassment campaigns, online and off, that intimidate doctors, legislators and even parents who’ve lost children to vaccine-preventable diseases.)

Still, when the message appeared in her inbox, she read it. “She didn’t start with fear and anger,” Hills remembers. “So it totally set the stage for me to be way more open to talking to her and listening.

“The first thing she said to me was, ‘Before we get into this, I just want to let you know you’re a good parent doing your best to make the best decisions you can make for your own kids.’ She treated me with dignity, and it totally disarmed me. She didn’t come in with her guns blazing of all the reasons I was wrong and all the reasons why I was hurting my children.”

The new conspiracy culture demands our attention as a pressing safety threat. And yet, as dangerous and racist as many theories are, it isn’t helpful to write off everyone who believes in them.

Instead, the public health advocate said Hills’ safety concerns were “perfectly legitimate.” But then she explained some of the science, like peer-reviewed double-blind studies, and set her loose. “She said, ‘You’re a smart, intelligent person; we’re both busy moms, so here’s the deal: Tara, do your research but check all the footnotes and make sure they are credible sources.’ I did do some research — and within two days, I called my doctor’s office.”

This interaction fits a pattern that author West has observed. Instead of demeaning and dismissing conspiracy theorists as tinfoil hat-wearing crackpots, he says we should try to acknowledge that they have genuine concerns that have somehow been twisted along the way.

“Tell them that it’s good that they have this questioning mind. But then try to explain to them that if you’ve got a truly open mind, you do have to give at least equal weight to both sides,” West says. He suggests being upfront about disagreements but also finding where you do agree and respecting that theorists are often being rational from their perspective.

“My approach is just to figure out what information they’re missing and try to communicate that to them in a way that doesn’t alienate them and doesn’t make them shut you off. You’ve got to maintain effective communication,” he says. “People do eventually change. It often seems like they don’t — and sometimes it seems like they’re getting worse — but over time, a lot of people I can get out of whatever rabbit hole they happen to be in.”

For Hills, the key to escaping conspiracy thinking is improving one’s media-literacy skills. “It’s one of the sad realities of our time that we live in the age of information, and people haven’t necessarily either been taught, or naturally developed, good [media] discernment,” she says. It “might not change things quickly, but we can change things generationally if schools can begin to teach kids the checklist of ‘how do I decide if this is a good piece of information that I should trust and post on my page or use for my report’.…Kids don’t just know that.”

Adults don’t know that, either. So if we want to get through this strange political time together, it’s time we started helping each other to learn.

This story first appeared in Broadview’s May 2020 issue with the title “Conspiracy culture.”

Broadview is an award-winning progressive Christian magazine, featuring stories about spirituality, justice and ethical living. For more of our content, subscribe to the magazine today.

Comments