A favourite cookie. A Christmas ritual. Tales from the old country. For the children and grandchildren of immigrants, links to a distant land may feel comforting and tinged with nostalgia. But there are complications, too: conflict, poverty and all the other reasons that drive people to uproot themselves.

Tap on a header to view each story

Morocco: Glimpses of heritage and humanity

Germany: Working through the past

Guyana: Unravelling the myth

___________________________________________________________________________

Finding connection in Morocco

By Claire Sibonney

Photography courtesy of the author

You may unsubscribe from any of our newsletters at any time.

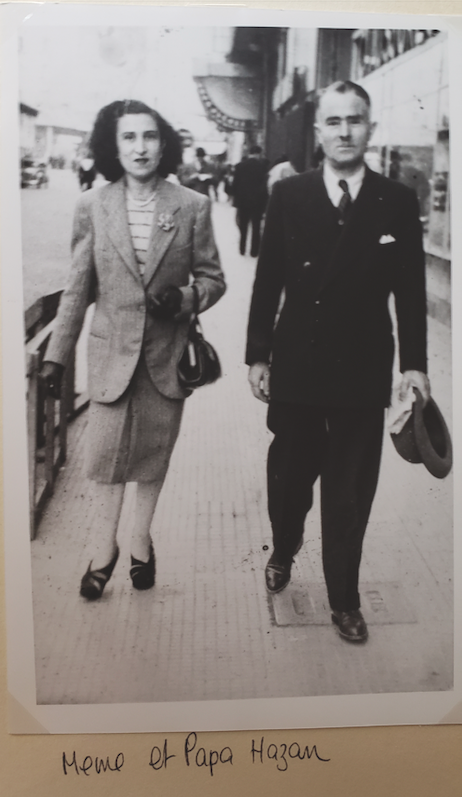

It was odd growing up as a Moroccan Jewish kid in Toronto. My twin sister and I were raised observing conservative Jewish traditions, but culturally and spiritually, we were Maghrebi, from the western part of North Africa. We went to a Moroccan synagogue where the prayers undulated in distinctly Sephardic melodies — inherited from our Jewish ancestors who lived in Spain and Portugal. At family celebrations like weddings, women would ululate in joyful tongue trills. At funerals, they wailed openly and cathartically.

My sister and I embraced our Moroccanness. We played dress-up in caftans with golden embroidery and had mint-tea parties with our grandmother’s silver teapot that she bought in a Casablanca souk. We put henna on our hands and hair and taught ourselves to belly dance. We were conversational in French (still widely spoken in Morocco) and could swear impressively in Arabic. My mother made feasts of couscous and tagine and, at home, my father wore his long, flowing white tunics called gandoura on Shabbat. While there were times we wished we could just be like everyone else — my dad answering the door in a “dress” was slightly mortifying — being Moroccan defined our immigrant experience.

Yet we had never seen where our people came from. We knew that we were Moroccan in our blood, but Israel was the only physical connection we had to a homeland. That was where much of my family settled after leaving Morocco — many of them are still there. My parents felt distanced from the place of their birth after trying to assimilate to new countries twice: first Israel, then Canada.

For my parents, leaving Morocco, a Muslim-majority country, signified a departure from “otherness” and an opportunity to join their own people in the Promised Land. But that otherness followed them. In Israel, they were others as Sephardic Jews, who are often looked down upon by Ashkenazi Jews from central and eastern Europe. Then they were others in Canada, with a compounded stigma of being both Jewish and Arab.

Still, my parents felt connected to Israel and took us back dozens of times. But not Morocco. The Israeli-Palestinian conflict further confused their feelings about their birth country as the Palestinian cause resonated widely among Muslim communities, turning people against Jews. Perhaps my parents thought Morocco was better left behind. But over time, not knowing the country made it hard to figure out who I was. I needed to discover this place I had never been but hoped to recognize myself in.

Finally, in October 2019 on a travel writing assignment, I made my first trip to Morocco at the age of 41. I wanted to start making sense of what my homeland means to me. I also wanted to explore what it means to identify as both Arab and Jewish in a world that sometimes sees these two identities as being at odds with each other.

Jews have lived in Morocco for more than 2,000 years. And while that history has mostly been viewed as tolerant and peaceful, it was not without some systemic discrimination and periodic attacks. As many as a quarter-million Jews lived in Morocco as recently as the 1940s, but it is estimated that fewer than 3,000 remain today.

“For if Jews trickled into Morocco during the ancient period and poured in after the Spanish Inquisition, they poured out of the country in a series of hiccupping waves in the middle of the 20th century…that cumulatively convinced the vast majority of Moroccan Jews that their beloved country, which sided with its Arab cousins in times of conflict, fell on the unsafe side of unpredictable,” writes the essayist Michael Frank in the New York Times.

Frank notes that while Jews were free to practise their religion in Morocco, they had to pay a special tax, couldn’t have certain jobs and were sometimes restricted on where to live. Still, Jews became known as dhimmi, or “protected people.” This protection ranged from creating the first mellah, a walled fortress-like Jewish quarter, next to the royal palace in Fez in the 15th century, to declaring that the country would not turn over its Jewish citizens during the Second World War, sparing them from the Holocaust.

Yet most of the Jewish community, including every member of my family, eventually chose to leave. My father and mother were only eight and 11 respectively when they joined the exodus to the new Jewish state of Israel. They each moved to Canada in their 20s, where they started a family.

To be honest, before I travelled to Morocco, I was uncertain about what kind of welcome I would receive. Political sentiment toward Jews there is known to be sensitive to Middle Eastern political events. Last fall, the peace process seemed once again derailed amid continued occupations in Palestinian areas. But the Morocco I encountered embraced me. I knew that Jewish-Moroccan expats from Israel and France were visiting in droves, but to see it with my own eyes and hear Hebrew being spoken in every hotel lobby felt surreal and comforting. It took all my Canadian self-restraint not to run to complete strangers and yell, “I’m a Moroccan Jew, too!”

It was a revelation that Morocco’s ties to its Jewish community remain strong. Casablanca is home to the only Jewish museum in the Arab world. I was captivated by the old photos and artifacts and intact synagogues. (It was also remarkable that the Muslim curator was an expert in Jewish studies.)

My first night in Casablanca, I visited a Jewish family and we celebrated the holiday of Sukkot. Hearing them sing the blessing in those Sephardic tunes of my childhood brought me to an alternate reality in which my family never left. The lavish feast they served with some of my Moroccan favourites — spicy cooked carrots, pastilla and meat “cigars” — made me feel at home and homesick all at once. But it wasn’t just the Jewish community who made me feel a kinship. From the police officers who escorted my cab to my hosts’ remote house, to my Muslim and native Amazigh guides, I was overwhelmed by both their protection and their generosity of spirit.

On the third day, my Casablanca guide, Ahmed El Aoufy, and I found the apartment building where my mother grew up. It was a modest three-storey walk-up, but its ornate Tiffany-blue gate stood out. I made my way up to the rooftop, where housecoats and sheets were drying on clotheslines. I pictured my mom as a young girl helping her housekeeper, Fatima, hang the laundry. My mom told me that Fatima would give her the equivalent of five cents if she would repeat a blessing for her only child: “Allah ykhali lik wlidek” (“May God bless you and your son”). The day my mom and her family left, Fatima couldn’t stay long; she was too upset to see my mom go. Maybe this shared bond between Muslims and Jews is what keeps drawing people like me back here, grateful for these glimpses of our heritage and humanity.

I spent the rest of my visit searching for other sentimental landmarks that my parents jotted down for me: a cinema, the Hebrew school, a synagogue named after my great uncle. Along the way, I discovered surprising treasures, like every variation of almond cookie from my childhood. Then there were a couple of vendors in the souks, who walked right up to me to say I had a “face Maroc.” It was so inexplicably flattering and gave me such a sense of belonging that I bought whatever they were selling.

After I said goodbye to Ahmed at the end of my visit, he sent me a text: “You make me proud to be a Moroccan.” Maybe it was just another overly effusive compliment to thank me for my business, but he had given me what I didn’t even know I needed. He saw me not as an “other” but as one of them. That alone was worth the journey to my homeland.

Claire Sibonney is a Toronto writer who travelled to Morocco as a guest of G Adventures. The company did not review this essay.

Back to top

___________________________________________________________________________

Wrestling with family history in Germany

By Isaac Würmann

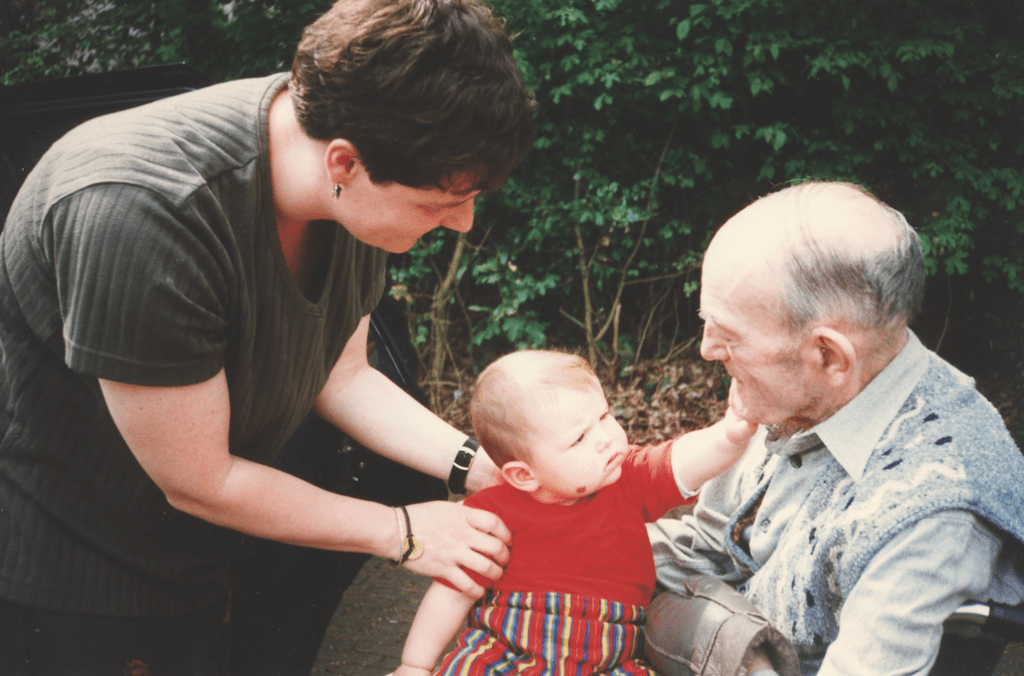

There’s a photo of me at eight months old, sitting in the lap of an elderly man in a wheelchair. I have a stern look on my face as I reach up to touch his sunken cheeks. The photo was taken in Bremen, a city in northern Germany, and the man is my great-grandfather. I was the first great-grandchild to be born, and he had paid for my mother and me to fly from Canada so that I could be introduced to my German family.

I met him once more, when we visited again three years later. He was unwell, and my mother wanted us to see him one last time before he died. The way she tells the story, he stayed alive just long enough for me to come and show him some toys as he lay in his hospital bed before he fell into a coma.

I was not born in Germany, nor was my mother. Her father was born in Bremen in 1940, and after meeting my Canadian grandmother in an Irish hostel and falling in love, he moved to Canada in the 1960s to be with her. Despite the fact that my closest genealogical connection to Germany is two generations behind me, my German heritage has always felt much closer.

When I started Grade 1 in Edmonton, my mother gave me a schultüte, a large cardboard cone filled with candies, toys and school supplies traditionally given to German children on their first day of school. In the house where I grew up, the bookshelf was stacked with German books. Around the holidays, I’d put my boot out for Sankt Nikolaus Tag, my family sang German carols and we’d have bunter teller (colourful plates filled with sweets) instead of stockings. But does celebrating these traditions make a person German? In my experience, identity is much more ambiguous. I don’t know if I have ever “felt German.” I do know that I want to know more about the stories heard in snippets at family gatherings, and I’ve made several attempts to learn the language in which those stories were sometimes told.

Although my mother and her sisters were all born in Canada, they spent a large part of their childhoods in Germany. They lived in a small town in the south for five years while my grandfather taught at CFB Baden-Söllingen. When she was 13, my mother returned for a summer, spending most of the time with her oma and opa in Bremen. My mother remembers how her oma, a seamstress, made clothes for everyone in the family, and how her opa kept a huge garden. But one of her strongest memories of that visit was sifting through old photographs spread out on the kitchen table. Among them was a photo of her oma wearing a brooch with a swastika on it, and a photo of her opa in a military uniform.

More on Broadview: A call to prayer brought me closer to my father

My relatives, like many people in Germany, have had to come to terms with our family’s involvement in the war. I now know that the frail man on whose lap I sat was a soldier during the Second World War, and that he was part of the Nazi occupation of the Greek island of Crete. As the Germans retreated at the end of the war, he was captured and held for years in a prisoner-of-war camp in Yugoslavia. My grandfather, his son, has stories about being a young boy at this time, moving with his mother and younger brother to a farmhouse to avoid the bombings of Bremen, and dashing across fields at night while “fireworks” exploded overhead. To be German is to reconcile these family stories with the shameful history they reveal.

There is a word in German for this reckoning. Vergangenheitsbewältigung, which roughly translates to “working through the past,” refers to the shame and remorse felt by Germans for their country’s complicity in the Holocaust and other atrocities of the Second World War. German-American author and illustrator Nora Krug describes her own process in her 2018 graphic memoir, Belonging. As she challenges the silences of her family’s past, Krug carefully wrestles with the idea of what it means to call Germany a homeland.

I love my family dearly and we remain close, but I don’t think I would ever say I am “proud” to be German. It’s a sentiment shared by Krug, who writes that being German felt like “history in our blood, shame in our genes.” Instead, my feelings of pride are much more attached to another part of my identity. To me, pride conjures images of rainbow flags and my community walking bravely through our city, and of the generations of activists who paved the way before us.

As I reckon with what it means to be German, I have found myself looking not to my biological family for answers, but to my chosen one. The concept of “chosen family” may have first been articulated by the American lesbian anthropologist Kath Weston in her 1991 book, Families We Choose: Lesbians, Gays, Kinship. Writing at the height of the AIDS epidemic, Weston described how communities of friends or lovers — rather than biological family — were necessary for the well-being and survival of gay men and their communities. There are countless other examples. In drag communities, this sense of queer kinship can extend over generations; drag artists sometimes adopt a last name to honour someone who performed decades before.

In recent years, as I’ve begun to understand my own queerness, I’ve felt myself connected to so many people and histories beyond my own family tree. Just as the branches of drag families extend generations into the past, I think about how mine reach back into the histories of queer communities before me. It’s these ideas about the chosen family that often guide me as I negotiate my connection to Germany, both spiritually and physically. Rather than returning to Bremen, I’ve spent most of my time in Berlin during recent trips. I feel drawn to that city in a way I don’t feel drawn to where my family has deeper roots.

Berlin has long been one of the great queer capitals of the world. By the 1880s, gay clubs were flourishing, largely without interference from police, and the world’s first gay magazine, Der Eigene, started there in 1896. A year later, Jewish physician Magnus Hirschfeld founded the Scientific-Humanitarian Committee, considered the first LGBTQ2 rights organization in history. It campaigned against the legal persecution of gay, bisexual and transgender men and women. By the 1920s, queer life in the city had coalesced around the Schöneberg neighbourhood, making it by some accounts the world’s first “gaybourhood.”

When the Nazis came to power, these thriving queer communities were forced underground. The Institute for Sex Research, which Hirschfeld started in 1919, was shut down in 1933 after the Nazi Party banned gay organizations and began purging gay clubs. The institute’s main administrator, who was also a Jew, was sent to a concentration camp. An estimated 100,000 homosexual people were arrested between 1933 and 1945, and 5,000 to 15,000 were sent to concentration camps.

The irony of how my family’s history intersects with the history of Germany’s queer communities is not lost on me. While my great-grandfather was supporting the Nazi occupation on Crete, other German soldiers were rounding up gay men in Berlin. Just as the pink triangles that were worn by gay men in concentration camps were reappropriated in the 1970s as a symbol of pride, I too am learning to reconcile my identity with a difficult history and to balance the shame and pride I feel about my heritage.

When I visit Berlin today, I search for the echoes of the queer communities that came before me. I look for them in the dark corners of the city’s legendary dance clubs and on the bustling streets of Schöneberg. But I also see the shadows of my great-grandfather and his legacy. When I visit Germany today, it is an exercise in holding these two families in my heart and mind at once.

Isaac Würmann is a writer in Winnipeg.

Back to top

___________________________________________________________________________

A journey through photos in Guyana

By Alyssa Bistonath

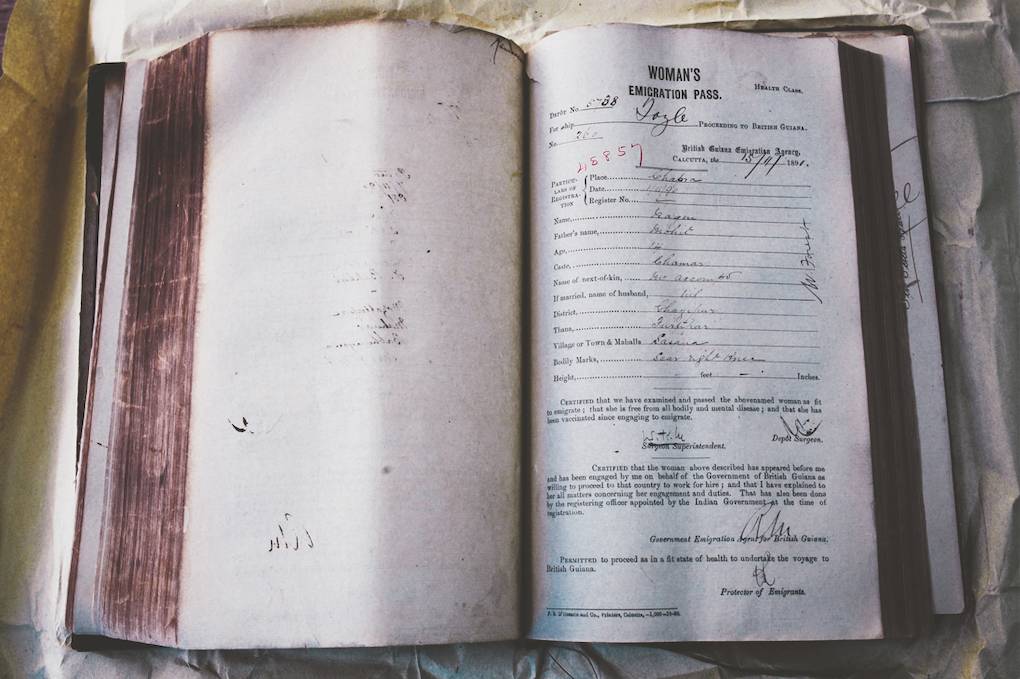

My homeland is a small South American country called Guyana, where the British brought my indentured ancestors from China and India. After independence, foreign interference in Guyana’s first election in 1968 fuelled a civil crisis that led half its population, including my parents, to leave.

The myth of Guyana that permeated my childhood in Canada was constructed from bits of lore, the smell of dinner and a handful of photographs. In 2015, I travelled twice to the villages where my parents grew up. I wanted to understand why the country’s diaspora characterized it as a paradise lost.

Photographing Guyana was like waking up from a dream. Through my lens, I learned to separate myth from reality. Home is not simply the land your ancestors once worked. Home is decoding your history and decolonizing your DNA.

Alyssa Bistonath is a photographer in Toronto.

Back to top

These features first appeared in Broadview’s July/August 2020 issue with the title “Origin stories.”

I hope you found this article from Broadview engaging. The magazine and its forerunners have been publishing continuously since 1829. We face a crisis today like no other in our 191-year history and we need your help. Would you consider a one-time gift to see us through this emergency?

We’re working hard to keep producing the print and digital versions of Broadview. We’ve adjusted our editorial plans to focus on coverage of the social, ethical and spiritual elements of the pandemic. But we can only deliver Broadview’s award-winning journalism if we can pay our bills. A single tax-receiptable gift right now is literally a lifeline.

Things will get better — we’ve overcome adversity before. But until then, we really need your help. No matter how large or small, I’m extremely grateful for your support.

Jocelyn Bell

Editor/Publisher