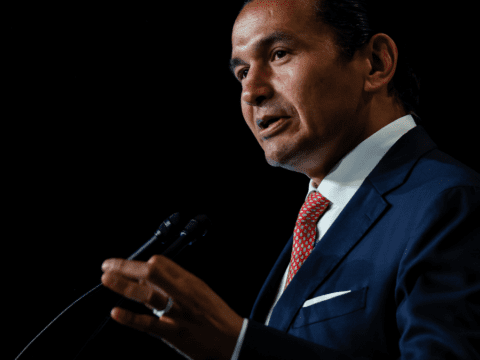

Late on Monday night, Jagmeet Singh stood at the podium, his wife Gurkiran Kaur at his side. His voice was unsteady as he repeatedly raised a glass of water to his lips, each sip deepening the tension. After a pause, he confirmed what many had expected: he would step down as leader of the New Democratic Party (NDP). The announcement, made hours after the NDP’s rout, may mark the end of an era for Canada’s political left — a movement with historic ties to Canadian progressive Christianity.

The federal election ushered in a minority government for Mark Carney’s Liberals, while Pierre Poilievre’s Conservatives made major gains — marking a decisive shift to the right.

You may unsubscribe from any of our newsletters at any time.

“There’s no doubt it’s a devastating loss [for the party],” says Jonathan Malloy, a political science professor at Carleton University. “They went down from [24] seats to seven. The leader lost his own seat. It was a very bad night for the NDP.” He attributes the collapse in part to fears of Donald Trump, with many voters turning to Carney as a safeguard.

The NDP, long seen as Canada’s political conscience, also fell below the 12-seat threshold for official party status — losing key privileges such as research funding, speaking time and staff resources.

The party has been here before. In 1993, under Audrey McLaughlin, it dropped to nine seats. Yet it rebounded, peaking in 2011, when Jack Layton led the “Orange Wave” to 103 seats and official Opposition status. Still, this recent defeat carries sharper implications — not just for the NDP, but for progressive politics in Canada.

More on Broadview:

Rev. Anne Gajerski-Cauley, who ran and lost as the NDP candidate in Brantford–Brant South–Six Nations, also calls the result “devastating.” While the majority of NDP voters wanted a Carney government, some long-time NDP strongholds like Windsor West and Kapuskasing-Timmins-Mushkegowuk flipped — not to Liberals, but to Conservatives. Once “boots, not suits” ridings, these blue-collar ridings are shifting right.

Malloy says this mirrors political shifts in the U.S. and U.K. “The Conservatives are no longer necessarily the upper-class party,” he explains. Many tradespeople earn solid wages but still feel left behind by progressive elites. “The Conservatives really appealed to that.”

But Gajerski-Cauley doesn’t think voters have rejected progressive ideals altogether. “Without this existential threat to our sovereignty and our economic dependence, I don’t believe people would have completely abandoned us,” she says. “It’s not that those folks abandoned our values.”

She concedes that Conservatives excel at punchy, memorable messaging. Where Conservatives offer digestible promises — like tax cuts — New Democrats propose structural reforms that are harder to explain in a sound bite.

A United Church minister who joined the NDP decades ago, Gajerski-Cauley says the party’s values still deeply align with her faith. “The values and vision of the NDP resonate most with the United Church,” she says. “That’s why I’m a New Democrat.”

Rev. Karen Orlandi, a United Church minister in St. Catharines, Ont., also ran — and lost — as an NDP candidate. Her decision to run was rooted in activism and the flexibility afforded by her downtown ministry at Silver Spire United, where demand for meals and shelter has surged. “I just don’t see anybody doing anything about it… and it’s just getting worse,” she says. “So, I think we need to stand up.”

“We’re all called to try to change the system for the better — for the people who can’t.”

For Orlandi, neither the Liberals nor Conservatives feel connected to the daily struggles she sees. Inspired by the Baptist preacher Tommy Douglas and the NDP’s social gospel roots, she views political activism as an extension of her ministry. “How do we create good community?” she asks.

“We are so good at loving kindness and not so hot at doing the justice part,” she says of the church. “Let’s change the damn system that put people in poverty in the first place.”

She’s discouraged by working-class voters turning right. “They’re getting sold a bill of goods….People are voting against their own best interest,” she says. She believes modest financial gains have made some voters more protective than progressive.

Still, she remains hopeful. “We’re all called to try to change the system for the better — for the people who can’t.”

Orlandi’s conviction, rooted in her faith, isn’t an anomaly in NDP history. From its founding, the party has drawn heavily from Christian socialism and the social gospel — a movement that saw spiritual renewal and social justice as two sides of the same coin.

Want to read more from Broadview? Consider subscribing to one of our newsletters.

The Co-operative Commonwealth Federation, precursor to the NDP, was formed in 1932 during the Great Depression by farmers, labour activists and clergy who believed capitalism had failed to serve the common good. For early leaders like Rev. J.S. Woodsworth and Douglas, socialism wasn’t a rejection of Christianity — it was its fulfillment.

The party’s strength was especially pronounced in Western Canada. Douglas became premier of Saskatchewan in 1944 — a landmark moment for the left. “It was a time when there was a real left-wing movement among farmers and workers,” says Malloy. Clergy played key leadership roles, inspired by their faith. (People have called the United Church “the NDP at prayer,” but the denomination has never officially backed a political party.)

But by the late 20th century, that influence waned. While ministers like the late Rev. Bill Blaikie — elected to Parliament in 1979 — still held seats, faith leaders gradually became a minority. “Increasingly, they’re an anachronism,” Malloy says. “I think Mr. Blaikie would have said the party was almost turning its back on religious groups.”

Still, even as its religious identity receded — and the evangelical right claimed much of the moral ground — the NDP remained rooted in values. “The party is based on a moral mission,” says Malloy, “whether it’s addressing inequality or confronting injustice.”

Singh, too, grounded his leadership in his Sikh beliefs in love and unity, consistently framing the NDP’s goals in moral terms. Under his watch, the party secured real policy wins — including a national dental care program — through its confidence-and-supply deal with the Liberals.

Whether the party can regain its footing remains to be seen. For Malloy, the NDP must confront defining questions: “What’s the point of a social democratic party in the 21st century? Can it merge blue-collar workers and progressive urban voters?”

As Singh reminded supporters in his farewell speech, the Sikh principle of chardi kala — a spirit of relentless optimism and courage — may be exactly what the party needs now.

***

Julie McGonegal is a writer in Elora, Ont.

Thanks for reading!

Did you know Broadview is the only media organization in Canada dedicated to covering progressive Christian news and views?

We are also a registered charity and rely on subscriptions and tax-deductible donations to keep our trustworthy, independent and award-winning journalism alive.

Please help us continue to share stories that open minds, inspire meaningful action and foster a world of compassion. Don’t wait. We can’t do it without you.

Here are some ways you can support us:

Thank you so very much for your generous support! Together, we can make a difference.

Jocelyn Bell, Editor/Publisher, CEO and Trisha Elliott, Executive Director

Not sure Bill Blaikie would say the NDP was turning its back on religious groups. What he did say was that the reason we hear so little about the religious left is because so many of its ideas and values had actually entered the Canadian mainstream. I’m looking past the “collapse of the NDP” headlines, well aware that many NDP voters – and even members – felt they had to vote Liberal in this election because of an existential threat to Canada. Thanks to Broadview for highlighting the NDP-United Church connection. (And indeed a connection with Anglican and some Catholic clergy.) Growing up in Saskatchewan, I was well aware of it. In my current conservative swath of Ontario, United Church members seem unaware of that whole history and current reality.

Ok – but aren’t you (in the order of importance):

1) a little worried that the United Church is so closely identified with one party? I often read about how bad it is that evangelicals back the Conservatives – how is this different? (Disclosure: not a Canadian so my question is about the collusion of religion & parties in general)

2) Perhaps rather than blaming the working class for not voting the “right way” (how progressive of you to know better!) perhaps you should be asking yourselves which progressive ideas are seen (and sometimes are in fact) damaging to your electorate.

Just 2 c. here. And thanks to everyone who ran for office even if they did not win.

Few points

The Liberals are far more left then the article suggests. They have not been centre politics since Pierre Trudeau, who introduced a more “social” political climate. As “father does”, Justin has pushed the bar further to the left.

The United Church has also pushed the Liberal government in the past (especially during the Person days) and lately has pushed the NDP’s because the Liberal’s haven’t worked fast enough to push the UCC social agenda.